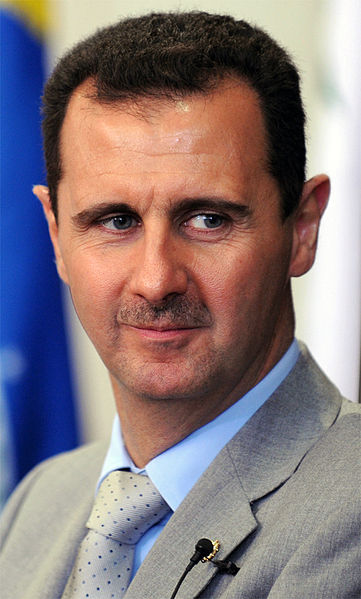

About a month after the Arab Spring rebellions washed up on the shores of Tunisia and Egypt, Syria’s cocky president, Bashar al-Assad, bragged that a popular uprising would never break out in Syria, a police state where dissent is strictly forbidden.

Four years on, Assad’s arrogant boast rings hollow. What began in March 2011 as a peaceful protest calling for democratic reform morphed into an armed revolt and then a fullblown civil war that has torn the country apart and claimed the lives of more than 200,000 Syrians.

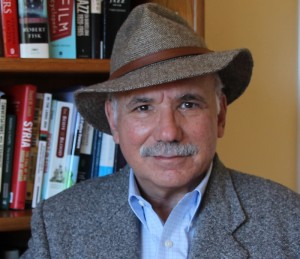

“History has rarely delivered a more stunning rebuttal,” writes Reese Erlich in Inside Syria (Prometheus Books), a lucid survey of the causes and effects of a struggle still playing out in Syria.

Erlich, an American journalist and frequent visitor to Syria, claims that conditions were ripe for a rebellion. Poverty and unemployment were on the rise, particularly among young Syrians, and Assad’s decision to privatize state-owned companies had benefited only a small, self-serving elite.

Syrians, too, could no longer bear living under a suffocating one-party regime that banned dissenting parties and outlawed freedom of speech and assembly and a free press. Before February 2011, even Facebook was off-limits to Syrians. Assad, nonetheless, was convinced that his Baathist regime was immune to insurrection.

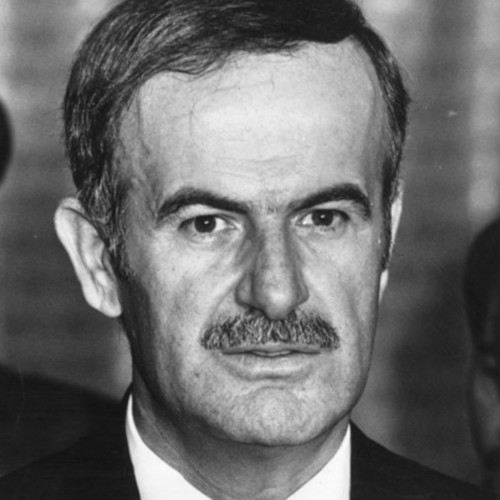

Ironically, Assad came to office in the guise of a reformer. He had lived and studied in Britain, spoke fluent English and acknowledged in his presidential acceptance speech that “old ideas” had no place in what would be a new and improved Syria. Assad, who had succeeded his father, Hafez, upon his sudden death in 2000, sounded like a breath of fresh air.

During his first year in office, he released political prisoners, licensed new newspapers and allowed the formation of non-governmental organizations critical of the Baathist Party’s monopoly of power. He even promised to tweak the constitution and end dictatorial rule.

After the first stirrings of revolt, Assad lifted the state of emergency, opened lines of communication with pliable opposition figures and granted citizenship to disenfranchised Kurds. But at the same time, he claimed that calls for democratic change were little more than efforts by the United States to weaken his government.

“Had he made such reforms in 2006, Assad would have been hailed as a far-sighted leader,” Erlich observes. “By 2011, it was too late. The uprising against Assad and his entire regime had begun, and there was no turning back.”

Anti-government demonstrations first erupted in the southern city of Daraa after police arrested and tortured several students who had scrawled anti-Assad graffiti on the walls of a school. Further non-violent protests occurred in Damascus and other cities. Facing its most serious challenge in a generation, the regime cracked down hard. Police and soldiers opened fire on peaceful demonstrators, killing scores of them. Soon enough, protesters — a combination of leftists, liberal secularists and conservative Muslims — fired back.

“The shift away from non-violent protest and toward armed struggle took place gradually,” Erlich writes. “Peaceful protest became increasingly difficult. Security forces surrounded mosques on Friday afternoons to prevent marches. Any attempt to hold a rally was quickly and violently dispersed.”

Amid this climate of hopelessness, defectors from the Syrian armed forces formed the Free Syrian Army. Subsequently, as the uprising deteriorated into a civil war, both sides resorted to targeted assassinations.

As Erlich points out, the protest movement initially had no leaders and no unifying ideology, and not even a short-term political program. Protesters, nevertheless, agreed on the need to overthrow Assad, hold free elections and establish a parliamentary system with civil liberties.

In response, the government claimed the protesters were backed by Israel, the United States, western European states and conservative Arab and Muslim states like Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

The Muslim Brotherhood — which had battled the Baathists in the late 1970s and early 1980s — stayed aloof from the fighting. “It had transformed itself politically in the 1990s in an effort to reverse its isolation inside Syria and to gain international legitimacy,” says Erlich.

But as the Syrian regime hardened its repressive policies, the Muslim Brotherhood — which drew inspiration from Turkey’s Islamist government — created an armed militia. Political Islam in Syria entrenched itself with the establishment of Jabhat al-Nusra, which was funded and armed by Al Qaeda’s affiliate in Iraq, the Islamic State of Iraq. The latter, which became the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, is today known as Islamic State.

Amid the chaos and bloodshed of the past four years, the Syrian military and intelligence services have remained loyal to Assad, a member of the Alawite sect, which had been an oppressed minority. In general, Assad also has been able to count on the backing of Sunni Baath Party members, Shiites, Christians and the Sunni business elite.

Despite having clung to power, Assad has failed to impose his will on the civil war. It’s at an impasse, with neither side strong enough to declare victory. “Syria remains in a military and political standoff,” Erlich writes in an apt appraisal of the current situation.

Iran, which formed an alliance with Syria more than 30 years ago, has been a faithful ally, having sent riot-control equipment, arms and military advisors to prop up Assad. Hezbollah, which has been armed by Syria and Iran, also has stood by Assad. Russia, an old friend, has rallied behind Assad as well. The United States and western European countries have come out in support of secular rebels.

The Palestinians are divided, though Hamas has backed the anti-Assad revolt.

The issue has split Israel, which has fought several wars with Syria. Some Israeli leaders have called for Assad’s ouster, while still others believe that the status quo best serves Israel’s interests.

In the meantime, the civil war is obliterating Syria. Cities are being destroyed. The economy lies in tatters. Millions of Syrians have been displaced from their homes. Millions have fled to neighboring countries like Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey.

Syria, a regional power until the 2011 uprising, is now the sick man of the Middle East, an appellation once derisively applied to the tottering Ottoman Empire. Many years may elapse before Syria can return to normalcy and rehabilitate itself as a functioning state.