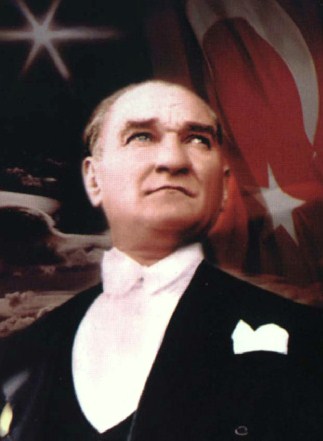

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has embarked on an awesome task: to undo some nine decades of history and reverse the secularization of his country begun by Kemal Ataturk, the revered first leader of the modern Turkish republic.

Erdogan’s project involves bringing Islam back into Turkish politics, and emphasizing, rather than negating, the glories of the Ottoman Empire, which collapsed following World War I. At its height, the empire ruled over the Balkans and parts of central Europe, much of the Middle East and large parts of North Africa.

His “New Turkey” summons up its Ottoman legacy and sponsorship of Sunni Islam.

A man with a mission, which began with the first victory of his Justice and Development (AK) Party in 2002, Erdogan, elected head of state last August, is moving full speed ahead, and is today politically almost unchallenged in Turkish politics.

Perhaps, despite the anti-clericalism of the Kemalist ideology, Islam was always “hiding in plain sight,” as it were, especially among the vast majority of the population living in rural Anatolia, outside a cosmopolitan city like Istanbul.

Historian and journalist Can Erimtan has noted that, while Islam was largely replaced by Turkish nationalism to supply a kind of social cement, “this form of ideological adhesive was nevertheless very much dependent upon Muslim solidarity.”

So, “though ostensibly ‘secular’ and unburdened by Islamic reaction,” he writes, “popular life to a large extent depended heavily upon Islam, its rituals, and formal organization.”

Erdogan has simply tapped into this reality.

Recent years “have seen a marked shift towards greater Islamic influence over education,” according to Batuhan Aydagul, an education analyst. The number of imam hatip (Sunni Islamic clerical training) schools has doubled in recent years.

Also, as part of the program of the re-socialization of children, this has been followed by Erdogan’s demand for classes on Islam for Muslim children entering primary schools.

He has also has directed schools to teach the old Ottoman version of Turkish, written in Arabic script, rather than in the Latin alphabet introduced by Ataturk.

Erdogan annulled a decades-long ban on wearing headscarves in public institutions and banned alcohol in public places between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. He explained he hoped to save new generations “from such un-Islamic habits.”

Anat Lapidot-Firilla, the executive director of the United States-Israel Educational Foundation and a specialist in Turkish politics, has noted that Erdogan’s worldview is much more “religious and conservative” than “nationalistic.” This may actually help heal the longstanding conflict with the country’s large Kurdish population.

Most Kurds are Sunni Muslims, after all, and this may in Erdogan’s mind be more salient than their ethnicity and language. After all, for the Ottomans, whose many subjects included non-Turks (in particular Arabs), religion was the primary marker of identity.

Erdogan has even begun to present himself as a defender of the faith outside of the Middle East.

On Feb. 25. the Austrian Parliament updated the country’s “Law on Islam,” to regulate how Islam is managed inside the country. It includes provisions requiring imams to be able to speak German, standardizing the translation of the Koran in the German language, and banning Islamic organizations from receiving foreign funding.

“We cannot accept any harm to Muslims because of this law and we will make every effort to prevent such harm,” Turkey’s Minister to the European Union, Volkan Bozkır, told the Anadolu News Agency a day later.

Erdogan has referred to the recent incidents of Islamophobia and biases against Muslims, especially in Europe. “The incidents are shifting to a different ground. We have to stop these biases,” he declared.

No friend of the Jewish state, Erdogan has accused Israel of deliberately killing Palestinian mothers. During last year’s presidential campaign, which coincided with the Gaza war between Israel and Hamas, he warned Israel it would “drown in the blood it sheds.” He also equated Israel’s actions to those of Hitler. Last December, Moshe Ya’alon, Israel’s defence minister, condemned Turkey for hosting members of Hamas.

In January, Turkey’s prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, compared Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to the Islamist militants whose attacks in Paris left 17 dead, saying both had committed crimes against humanity. As well, Erdogan criticized Netanyahu’s attendance at a Paris solidarity march following the murders.

In turn, Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Liberman called the Turkish president an “antisemitic bully.”

Meanwhile, Erdogan has built a new presidential palace complex on the outskirts of the capital, Ankara, replacing Ataturk’s, located in the secular Cankaya district.

Nicknamed Ak Saray, or the White Palace, it has at least 1,100 rooms. Is this a symbolic gesture meant to emphasize the end of the secular republic and the birth of a neo-Ottoman state?

A video of the complex, with the national anthem playing in the background, was posted in late October. But some people noticed that, while the words were the same, the martial drumming and brass instruments made the music sound as if it were being played by an Ottoman-era military band.

Erdogan hopes for a large enough AK win in the coming June 2015 parliamentary elections to enable the legislature to pass a constitutional change creating a powerful presidential system. He is clearly planning for a long stay.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.