The communist approach to the Holocaust was, in a word, bloodless.

While the Soviet Union and the mostly compliant satellite states in Eastern Europe never entirely banned discussion and memorialization of the Holocaust, they often muffled the full story of the extermination of six million Jews and dissolved it into the general narrative of the suffering their respective populations had endured under Nazi Germany’s brutal occupation.

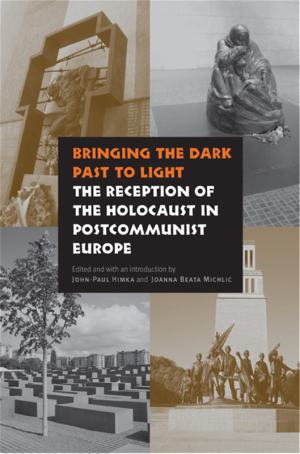

As far as communist governments were generally concerned, “there was no room for public mourning and empathy for the dead Jews and the destroyed world of Eastern European Jewish civilization,” write John-Paul Himka and Joanne Beata Michlic, the co-editors of Bringing The Dark Past To Light, a book of informative and perceptive essays published by University of Nebraska Press.

Apart from shunting the Holocaust into remote and largely inaccessible corners, these regimes were loathe to acknowledge that prewar and wartime antisemitism had been a problem. Furthermore, communist leaders had no compunctions about pandering to popular antisemitic attitudes and tropes when it suited their purposes.

Himka and Michlic classify Holocaust memory under three broad categories.

“Remembering to remember” recognized the void left by the mass murder of Jews and attempted to integrate Jewish history into national history. “Remembering to benefit” sought to achieve tangible goals from commemorating the Holocaust. “Remembering to forget” regarded the Holocaust as an affront to collective history, memory and identity.

During the communist era, the last two forms of memory were prevalent. Since the dissolution of communism, the first two have been on the ascendancy. These complex issues, playing out in nations ranging from Hungary and Croatia to Lithuania and Serbia, are examined and clarified in 21 cogent essays in this illuminating volume of 778 pages.

In East Germany, for example, the Holocaust had no more than a “modest presence” in official remembrance from 1949 to 1989, writes Peter Monteath. The regime recognized the mistreatment and murder of German Jews, but only within limits.

The authorities in Belarus, once a vital center of Jewish life, virtually disregarded the Holocaust. “Until the mid-1990s, the history of the war was written without any acknowledgement that the Jews were the prime targets of the Nazis,” says Per Anders Rudling. “The Holocaust was de-ethnicized. The Jewish tragedy, but also Jewish resistance, was marginalized or overlooked …” Even today, school textbooks in Belarus pay only lip service to the Holocaust.

In Hungary, where more than 400,000 Jews were murdered, the ruling Communist Party prosecuted and executed war criminals and briefly permitted accounts of the Holocaust to be published, says Paul Hanebrink.

The communists soon ended any serious consideration of Hungary’s complicity in the Holocaust and welcomed former fascists into their ranks. Post-communist governments, however, have recognized Holocaust Remembrance Day and issued new textbooks to address the Holocaust.

Poland, home to Europe’s biggest concentration of Jews prior to 1939, clamped down sharply on scholars who raised challenging questions about dark aspects of Polish attitudes and actions toward the Jewish population, says Michlic and Malgorzata Melchior.

During the late 1960s, the nationalist faction within the Communist Party, led by Mieczyslaw Moczar, decreed that an emphasis on the destruction of Polish Jewry posed a threat to the concept of ethnic Polish wartime martyrdom.

By the late 1990s, though, Poland was awash with monographs about the Holocaust. Of late, Poland has made vast strides in coming to terms with the Holocaust.

Romania — a country where prewar antisemitism was intense — played an active role in the Holocaust by virtue of the murderous activities of the Iron Guard militia and the fascist leadership of Ion Antonescu.

But in official postwar books, the issue of antisemitism was avoided, while the word Holocaust was never used, note Felicia Waldman and Mihai Chioveanu.

With Romania eager to gain membership in the European Union and the NATO military alliance, the Romanian government commemorated Holocaust Remembrance Day and conceded that antisemitism had been a state-sponsored phenomenon.

Contemporary Russia has a mixed record with respect to the Holocaust.

At an appearance at the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp in 2005, President Vladimir Putin spoke of the inhuman “fascist” ideas that gave rise to the Holocaust. But never once in his speech did he mention the Jewish identity of the victims, writes Klas-Goran Karlsson.

Similarly, while the Holocaust has been a legitimate research topic in Russia since the late 1990s, “there is still a disinclination to acknowledge that the vast majority of Auschwitz victims were Jews.” Nevertheless, he points out, “there has been some increased interest in the Holocaust among Russian politicians and state authorities.”

In Ukraine, where the Babi Yar massacre took place, a discussion of the Holocaust was largely stifled in the first four decades of communist rule, says Himka. Holocaust themes were introduced into school texts starting in 1993, but such books tend to treat the Holocaust as an event that occurred in Germany and Poland rather than in Ukraine as well.

The rescue of Bulgarian Jewry during the war has become an “important building block” in fashioning Bulgaria’s image in the post-communist/Cold War period, says Joseph Benatov. But the communist regime under Todor Zhivkov paid attention to that theme, too, he notes.

The fate of Albania’s minuscule prewar Jewish community, consisting of 156 native Jews, has generated little notice among scholars inside Albania and abroad.

This is surprising, given the fact that the Albanian government blocked the implementation of the Holocaust within its borders, one of the very few European nations to do so. On the other hand, as Daniel Perez observes, Germany did not aggressively seek to deport or exterminate the few Jews after occupying Albania in November 1943.

Since the death of its longtime dictator, Enver Hoxha, whose attitude to the Holocaust goes unmentioned in Perez’s essay, Albanian officials, historians and journalists have expressed only a lukewarm interest in it. Indeed, Apostol Kotani’s Jews in Albania Through the Centuries, published in 1995, is the sole monograph on the modern history of Jews in Albania written by an Albanian author. Nevertheless, Albanians believe they share a common history of persecution with Jews.

The manner in which Nazi-occupied nations have responded to the Holocaust since the fall of communism is a subject of no small importance. Fortunately, Bringing The Dark Past To Light addresses this topic seriously and comprehensively.