The 10-day Toronto Jewish Film Festival, one of the largest of its kind in the world, gets under way on April 30 with a huge selection of movies from all corners of the globe.

A preview:

Zionism and Israel loom large at the forthcoming festival, judging by three films: The Zionist Idea, An Untold Diplomatic History: France and Israel Since 1948 and Haven.

Joseph Dorman’s and Oren Rudavsky’s two hour-plus documentary, The Zionist Idea, is nothing if not thorough. It examines the evolution of the modern Zionist movement from the 1880s onward and the birth of the Jewish state in 1948.

Dorman and Rudavsky try to achieve a sense of balance and nuance through the medium of interviews with Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs, some of whom are citizens of Israel. They throw in vintage photographs and file footage to bulk up their film, which is alternatively informative, sober, impassioned and didactic.

The tone is set at the very outset.

Hillel Halkin, an Israeli writer with a conservative bent, describes Zionism as a movement whose objective was to normalize Jewish existence and bring about a revolution in Jewish life. Orly Noy, a left-wing peace activist, compares Zionism to a person who jumps out of a burning building and lands on someone’s head.

Hanan Ashrawi, a member of the PLO’s executive committee, takes up the thread of Noy’s argument with her claim that Zionism, for all its material accomplishments, failed because it’s oppressive and exclusive with respect to the Palestinians.

Jumping back to the late 19th century, the film notes that the 1881 pogroms in Russia prompted three Jewish responses. Two million Jews immigrated to the United States. Still other Jews turned to socialism or Jewish nationalism, of which Leo Pinsker was an ardent advocate. In his ground-breaking volume, Autoemancipation, he wrote, “Jews must exist as a nation.”

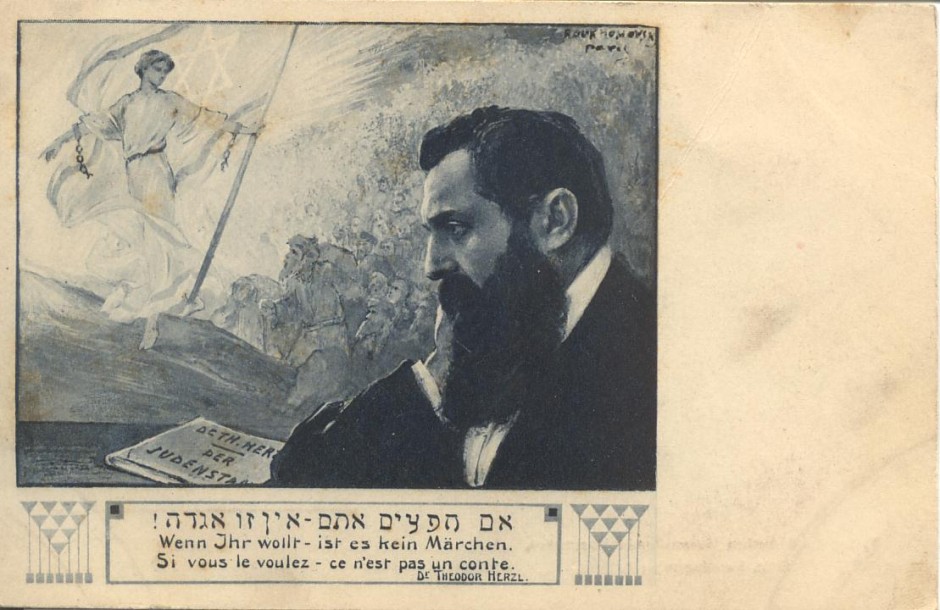

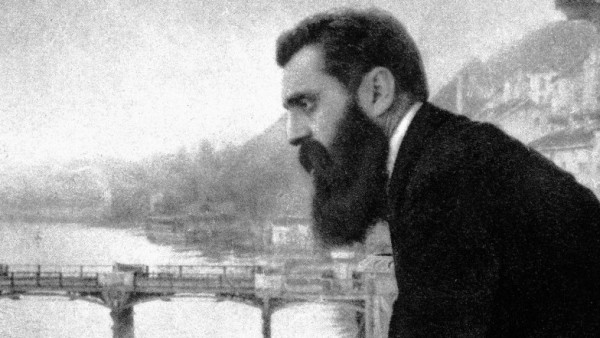

Young Russian Jews burning with Zionist zeal arrived in Palestine, an Ottoman backwater, and established settlements like Zichron Yaakov in the spirit of Tolstoyan idealism. A Viennese journalist named Theodor Herzl, grappling with the failure of Jews to integrate themselves into European society due to endemic antisemitism, founded the political Zionist movement. Zionism, deeply steeped in secularism, was thus a European phenomenon, influenced and inspired by European nationalist movements.

Halkin makes a good point in arguing that Zionism had an ambivalent relationship with Judaism, affirming yet rejecting it. Meron Benvenisti, the former deputy mayor of Jerusalem, says that Zionism attempted to create a “new land” for a “new people.”

The filmmakers correctly call the 1917 Balfour Declaration — the seminal British letter which recognized the right of Jews to a Jewish homeland in Palestine — the first international recognition of Zionism. It was a singular victory for the Zionist movement, notwithstanding the fact that Jews comprised only six percent of Palestine’s population.

The Balfour Declaration was a wakeup call for its Arab inhabitants. From that point onward, Palestinian nationalism was at war with Zionism. Starting in the early 1920s, bouts of organized Arab violence shook the Yishuv, the Jewish community

Under the British Mandate, the Yishuv grew rapidly. This was particularly true after the rise of fascism in Europe. More than 174,000 Jewish refugees arrived in Palestine within a three year period after 1933, doubling Palestine’s Jewish population.

The 1947 Palestine partition plan, accepted by the majority of Jews, was rejected by the Palestinians. The first Arab-Israeli war resulted in the flight of 700,000 Palestinians from their homes, but the film leaves the impression that the Haganah — the main Jewish fighting force — was not guided by an official policy of expulsion, but that Transjordan’s Arab Legion forcibly expelled Jews from eastern Jerusalem. As a result, there was an implicit population exchange, says Tel Aviv University professor Anita Shapira.

When the war ended, Israel had one-third more territory than it had been entitled to under the UN partition plan. The birth of Israel aroused deep enmity in the Arab world, forcing hundreds of thousands of Jews to emigrate from Arab lands. Most of them ended up in Israel.

The Zionist Idea spends considerable time on the Six Day War and its fallout. Israel’s conquest of the West Bank — Judea and Samaria — was a watershed, giving Israel control of historic Palestine. The war unleashed what one Israeli scholar describes as “redemptive messianic forces.” Gush Emunim, which sought to build settlements in the West Bank, became the vanguard of Zionism. Several of its leaders, including Yoel Ben Nun, are interviewed.

The Likud’s victory in the 1977 election is rightly assessed as the moment the right-wing Zionist Revisionist movement, with Menachem Begin at the helm, assumed power in Israel. Begin, an admirer and supporter of the settlement project, ordered the construction of dozens of settlements to prevent the emergence of a Palestinian state.

The first Palestinian uprising broke out in 1987 and became a source of concern to middle-of-the-road Israelis such as the writer and commentator Yossi Klein Halevi, an American immigrant who made aliyah in 1982. The price of maintaining the “legitimate Jewish claim to Judea and Samaria” had become intolerable, he observes.

Yitzhak Rabin, twice Israel’s prime minister, accepted partition as a principle before and after the signing of the 1993 Oslo accord. Rabin’s assassination at the hands of Yigal Amir, a far-right Jewish nationalist, exacerbated the left/right schisms dividing Israelis along ideological lines.

The Zionist Idea reaches its denouement as Mordechai Bar-On, an ex-Israeli general, laments the rightward direction Zionism has taken since the Six Day War. An old school Israeli patriot whose son-in-law is a Palestinian, he expresses sadness that contemporary Zionism has cornered itself into the belief that only the Jewish people have a rightful claim to historic Palestine.

***

Until the 1967 Six Day War, Israel and France were bound together in an unusually close relationship. It all soured in a welter of mutual recriminations, proving the adage that relations between nations are based on interests rather than friendship. That’s the theme of Camille Clavelle’s weighty documentary, An Untold Diplomatic History: France and Israel Since 1948.

The title is misleading. Israel’s relations with France have been documented in monographs and books by a plethora of scholars, but this may be the first comprehensive film on the topic.

France, after the antisemitic Vichy interregnum, became a hub for illegal Jewish immigration to British Palestine. Lest it be forgotten, the Exodus, a ship filled with Jewish Holocaust survivors, set off from the French port of Sete.

Although it had clear interests in the Arab world, France voted for the 1947 United Nations Palestine partition plan, one of 33 countries to do so. In Clavelle’s judgment, France and Israel formed an alliance after Egypt’s nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956. France calculated that the demise of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser would ensure a French victory in the war in Algeria.

The military campaign against Egypt was planned by France, Britain and Israel in the French town of Sevres. Shimon Peres, who served as Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s aide, discusses that meeting.

France’s relations with Israel deepened after the 1956 war. Apart from selling weaponry to Israel, France agreed to build an atomic reactor in Dimona. “There was a feeling of great friendship and closeness,” says former Israeli diplomat Paul Kedar.

French intellectuals on the left, as exemplified by Jean-Paul Sartre, supported Israel. And the kibbutz was regarded as a miracle in the desert.

Charles de Gaulle, France’s new president, loosened the bonds, though Ben-Gurion visited France in 1960 and 1961, When France informed Israel it intended to end its secret program of nuclear cooperation, Peres warned the French foreign minister that he would publicize its details and thereby embarrass France. Cowed by the threat, France agreed to finish building the Dimona reactor.

The incident was a foretaste of things to come.

On the eve of the Six Day War, de Gaulle told Israeli Foreign Minister Abba Eban, “Don’t fire the first shot.” De Gaulle, certain that Nasser had no intention of going to war, feared that Soviet intervention would spark a world war.

Three days before hostilities erupted, de Gaulle announced an arms embargo. Five months later, in an antisemitic diatribe, he denigrated Jews as an “elite,”domineering” and “self-assured” people. And he blasted Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, correctly warning that it would produce an outpouring of Palestinian terrorism. Samy Cohen, a French scholar, says that de Gaulle’s comments traumatized French Jews and Israel and spelled the end of Israel’s entente with France.

France adopted a policy calling for Israel’s withdrawal from the occupied territories in exchange for a peace agreement with the Arabs.

DeGaulle imposed a total arms embargo on Israel after Israel’s daring raid on Beirut airport in December 1968. France withheld 50 Mirage jets Israel had bought. De Gaulle’s successor, Maurice Pompidou, honored de Gaulle’s policy, forcing Israel to acquire Mirage blueprints by stealth and to make off with high-speed patrol boats from the port of Cherbourgh.

The next president, Valery Giscard d’Estaing, distanced France even further away from Israel as he cultivated ties with Arab states and the PLO. His successor, Francois Mitterrand, normalized relations with Israel while calling for the creation of a Palestinian state.

The 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon soured Israel’s relations with France. The Sabra and Shatila massacre, which occurred toward the close of that war, eroded Israel’s image and heightened sympathy for the Palestinians in France, says Jacques Huntzinger, a former French ambassador to Israel.

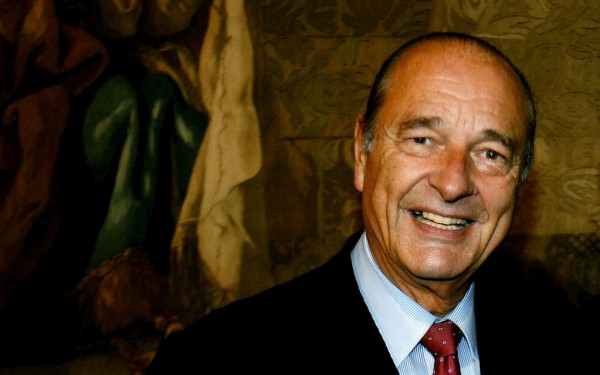

President Jacques Chirac tried to be even-handed, but a mob scene in East Jerusalem in which he was involved triggered a cause celebre and ruffled feathers. President Nicolas Sarkozy, widely considered to be Israel’s friend, infuriated Israel by suggesting that the Palestinian Authority’s status at the United Nations should be upgraded.

The film suggests that the Arab Spring rebellions have shifted France’s attention away from the Arab-Israeli conflict. But this supposition has been overtaken by events. According to the latest news, France may soon sponsor a United Nations resolution on Palestinian statehood.

***

Amikam Kovner’s Haven unfolds during the Second Lebanon War as Hezbollah missiles drive civilians in vulnerable northern Israeli towns to the coastal plain. Two of these war-scarred refugees, Motti and Keren, find temporary refuge in the cramped Tel Aviv apartment of Yali (Lana Ettinger) and her husband, Boaz (Nevo Kimchi).

Motti (Oshri Cohen), a talkative fellow, is grateful for the hospitality. “All Israelis are brothers,” he gushes.

“They seem like a nice couple,” Yali tells Boaz.

The secular hosts soon realize that their guests are observant Jews and therefore out of sync with their values and opinions. Motti asks for disposable plates, since he eats only kosher food. Boaz and Motti clash over an anticipated ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah. As Boaz grows weary of his guests, Motti casts carnal eyes on Yali. As the sparks fly, pent-up tensions build up between Boaz and Yali.

Haven, ably directed by Kovner, is a taut psychological drama with a fine cast.