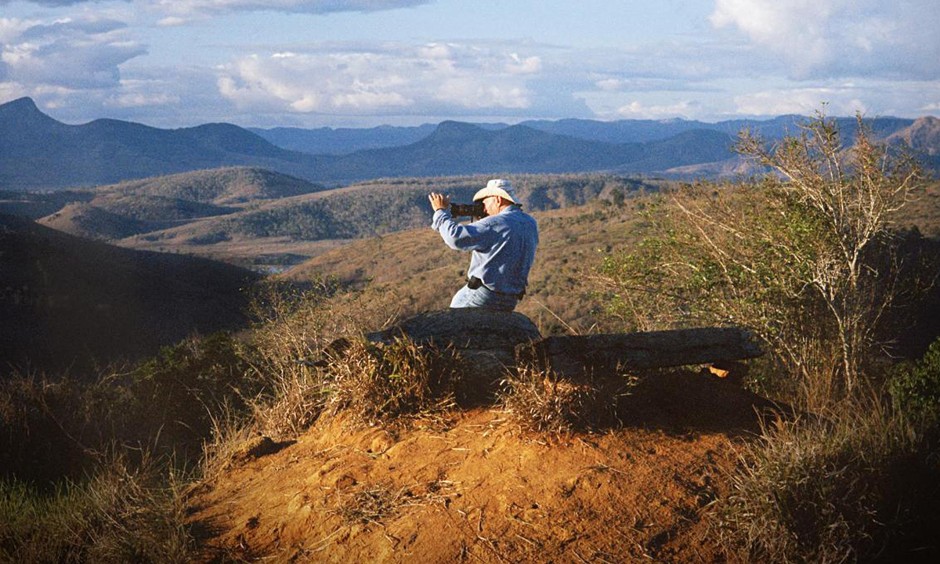

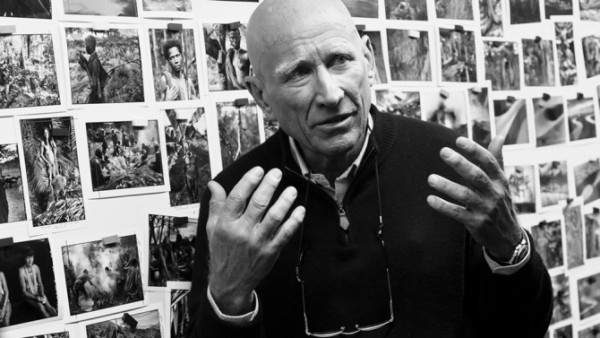

Brazilian photographer Sebastiao Salgado has travelled the world documenting the folly and diversity of mankind and the allure of nature.

Salgado’s son, Juliano, has made a poignant documentary about him. The Salt of the Earth, which opens in Canada on April 10, is alternatively majestic and depressing. Salgado’s black and white photographs are sharp and graphic, a testament to his artistic sensibility and technical skill. He’s a master of light and shadow.

His son’s film hops, skips and jumps around the globe, focusing on gold miners in Brazil, primitive hunter/gatherers in Indonesia, polar bears and walruses in Siberia, fringe communities in South America, starving Africans in Ethiopia, Canadian fire fighters dousing oil wells in Kuwait set alight by Saddam Hussein’s foot soldiers, refugees fleeing genocide in Rwanda, and Serbs, Croatians and Bosnians dodging violence in the failed state of Yugoslavia.

Early on in his sharply-observed film, Juliano asks, Who would be interested in the life of a photographer?

Judging by its contents, just about anyone who has a beating heart and a deep enough soul.

Salgado, 71, was born on a farm in the depths of Brazil. He studied economics and was heading toward a career in the World Bank when fate intervened. Lelia, his wife, lent him her camera and he took to it like a duck to water. He liked photography and, in a risky gamble, left his secure job to devote himself to photography, evolving into one of the world’s finest practitioners of the art.

He and his wife left Brazil when it was under the rule of a military dictatorship, not returning until the advent of democracy.

Salgado’s photographs of thousands of miners swarming over gold fields like so many ants are striking. His photographs of the virtually untouched and unspoiled Pali people of Indonesia’s remote highlands are evocative.

In his series, Other Americas, Salgado spent two years taking pictures of people living on the periphery of their respective societies. The photographs are like etchings. “The power of a portrait lies in the fraction of a second,” he says.

Salgado is a patient man. In the wilds of Siberia, he creeps along the ground waiting for the right moment to photograph a solitary polar bear or a group of walruses playing in water. This is nature at its purest best.

Travelling to Ethiopia and the Sahel, he comes face to face with the misery of mass starvation. In Kuwait, he watches Canadians, their faces coated in soot and oil, putting out gigantic fires. In Rwanda, Salgado is a witness to genocide.

The brutalities of the civil war in the former Yugoslavia shake him to his core. “It was strange all this was happening in Europe at the end of the 20th century,” he comments, perhaps forgetting the Holocaust that snuffed out the lives of six million European Jews.

“We humans are terrible animals,” he adds. “Our history is a history of wars, a story of repression.”

The Salt of the Earth, a son’s cinematic tribute to a father, shows us a universe bathed in beauty and weighed down by tragedy.