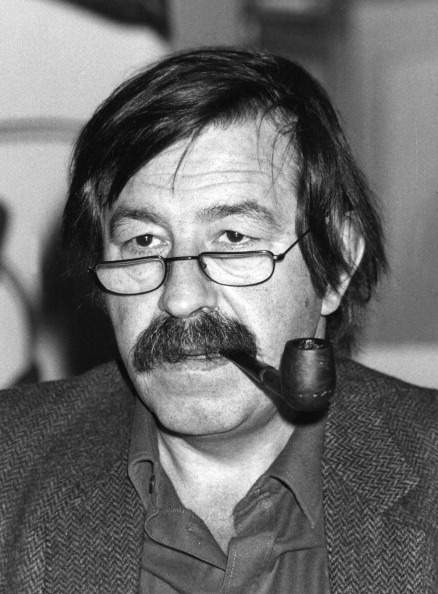

When the death of Gunter Grass — Germany’s most illustrious postwar novelist — was announced on April 13, some critics were only too eager to seize upon two glaring missteps which dimmed his otherwise stellar reputation.

Describing him as a hypocrite and a fraud, they castigated Grass for having concealed his membership in the Waffen-SS during World War II. Branding him an antisemite, they took him to task for having singled out Israel as a threat to world peace.

Granted, these were egregious lapses of judgment on his part. But is this how Grass should be exclusively remembered?

The answer is a resounding no.

A Nobel Prize laureate, he was the moral conscience of his generation. Through novels like the The Tin Drum, Cat and Mouse and Dog Years, he played a vital and outsize role in Germany’s acknowledgement of, confrontation with and atonement for its Nazi past.

During the 1950s and 1960s, when politicians in western Germany focused on rebuilding and revitalizing a great nation that had mortgaged its values and soul to Nazism, Grass forcefully challenged their amnesia and complacency. An equal opportunity moralist, he also accused the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches of having been accomplices to Nazi crimes.

To his everlasting credit, Grass was intent on contemplating and exposing Germany’s descent into the purgatory of National Socialism. Particularly interested in reaching young and impressionable minds, he said an interview in 1991: “It has been very important to tell the younger generation how it really happened, that it happened in daylight, and very slowly and methodically.”

Nazism was an ugly interregnum in the broad canvas of German history, but it had the explicit or tacit support of most Germans, who were swept up by the tide of chauvinism and xenophobia. Grass, thoroughly brainwashed by the insidious appeal of Nazi propaganda, counted himself as one of Adolf Hitler’s ardent supporters. As he later admitted, he was a true believer, as were tens of millions of Germans.

Grass was conscripted into the Waffen-SS — a criminal organization that committed despicable war crimes during the Holocaust — in 1944. He had previously claimed to have been a flakhelfer, a student manning anti-aircraft batteries. Not until his memoir, Peeling the Onion, was published in 2006 did he finally came clean about his own questionable past. “It was a weight on me,” he told the Frankfurter Allgemeine. “My silence over all these years is one of the reasons I wrote the book. It had to come out in the end.”

True enough.

With this disclosure, Grass was mercilessly excoriated as a liar and arch hypocrite. But within the context of the times, he was not altogether unique, since many of his fellow Germans had expediently chosen to burnish their biographies.

Having emerged from the war unscathed, and having discovered to his horror the enormity of Nazi crimes against humanity, Grass became a pacifist. He gravitated toward the Social Democratic Party. Led by Willy Brandt — an exile from Nazism — it had been brutally suppressed by the Nazis.

In his novels, plays, essays and speeches, Grass lambasted Germany’s militaristic tradition and took it upon himself to be a cheerleader for West Germany’s transition to democracy.

Grass, always attentive to backsliding, condemned West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl for having invited U.S. President Ronald Reagan to visit a cemetery in Bitburg where, as it happened, 49 members of the Waffen-SS were buried. This scandalous incident, which occurred in 1985, touched off yet another round of agonizing soul-searching, reminding Germans yet again that the past has a way of intruding into the present.

Germany’s ascent toward reunification, following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, provided another platform for Grass to vent his spleen. Never less than outspoken, he expressed concern that a unified powerful Germany might threaten peace.

Invoking the specter of Auschwitz — where about one million Jews were murdered — Grass declared that a people who had conceived and implemented a genocidal agenda did not deserve unity. As he put it, “Auschwitz speaks against even a right to self-determination that is enjoyed by all other people. We cannot get past Auschwitz. We should not even try … because Auschwitz belongs to us (and) is branded into our history…”

Amidst the 1991 Gulf War, which pitted Iraq against the United States and its allies, newspapers reported that German companies had sold arms and dual-use equipment to Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime. Grass was aghast that, in their “unchecked lust for profit,” German industry had stooped so low.

It was an embarrassing moment of truth for Germany, a close ally of Israel.

During the war, Iraq — Israel’s arch foe — fired 39 Scud missiles at Israeli cities, causing considerable property damage. Shamed by the revelations of German complicity in Iraq’s aggression, Germany’s foreign minister, Heinz Dietrich Genscher, hastily visited Israel, promising to build Dolphin submarines for the Israeli navy at Berlin’s expense.

In 2012, amid growing international fears that Israel might be tempted to bomb Iran’s nuclear sites, Grass wrote What Must Be Said, a nine-stanza, 69-line poem for the Suddeutsche Zeitung in which he baldly accused Israel of imperilling the peace of the world, chided Germany for having supplied Israel with submarines and called for the supervision of Israel’s and Iran’s nuclear programs.

“Why do I say only now, aged and with my last drop of ink, that the nuclear power Israel endangers an already fragile world peace? Because that must be said which may already be too late to say tomorrow.”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu rebuked Grass. “It is Iran, not Israel, that threatens other states with annihilation,” he charged. Still other Israelis said that, as a former Waffen-SS soldier, Grass had absolutely no right to criticize Israel.

Thrown back on his heels by Israel’s harsh reaction, Grass offered an explanation, saying he had meant to attack not the state of Israel but the policies of its right-wing government.

By then, the damage had been done, with many Israelis regarding Grass as an enemy. Certainly, Grass went too far by lumping Israel together with Iran and by accusing Israel of being a menace to peace.

But to be fair, the sum total of Grass’ life was far larger than his insignificant and insipid poem and his fleeting fling with Nazism.