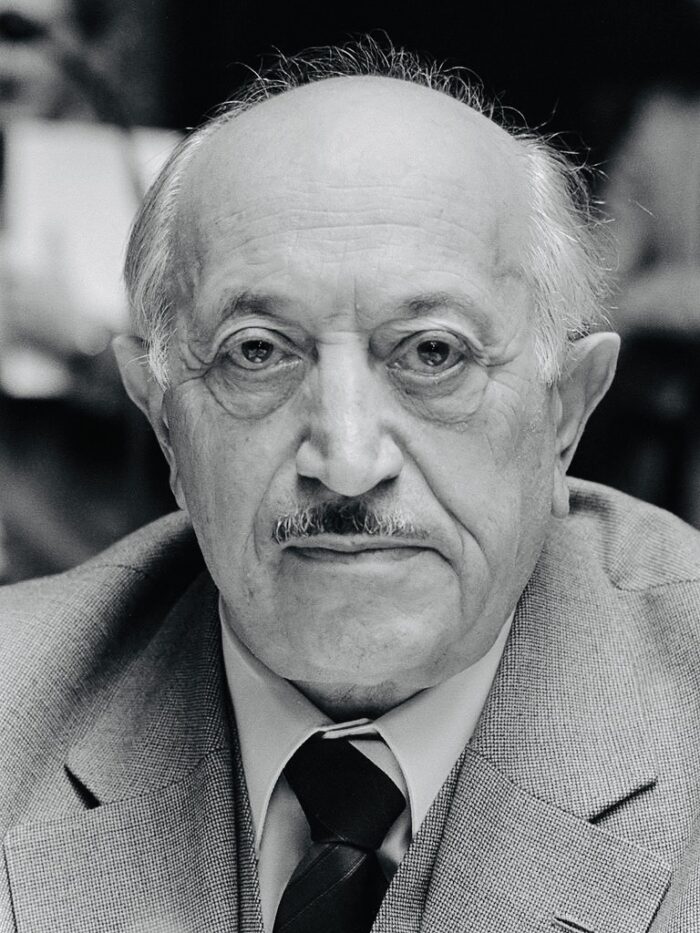

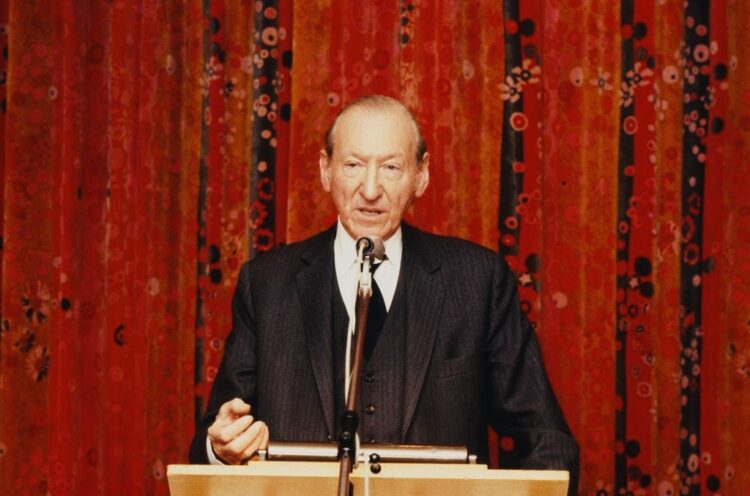

One of the most successful European politicians of the 20th century, Bruno Kreisky, was an Austrian Jew who was successively foreign minister of Austria, leader of Austria’s Socialist Party, and, from 1970 to 1983, Austria’s longest serving and only Jewish chancellor.

Kreisky is the subject of Daniel Ascheim’s biography, Kreisky, Israel, and Jewish Identity, published by the University of New Orleans Press. Ascheim, an Israeli diplomat, describes him as controversial and forward-thinking and compares him favorably to two Jewish French prime ministers, Leon Blum and Pierre-Mendes-France, and to one of Germany’s foreign ministers, Walther Rathenau, who was also Jewish.

As Ascheim acknowledges, Kreisky (1911-1990) has been profiled in books and articles, but his “ambitious and complex” relationship to his Jewishness, Israel and Zionism has been only partially researched.

In this balanced, erudite and wide-ranging book, he focuses on some of the key moments in Kreisky’s career: his embrace of the postwar doctrine that Austria was the first victim of German aggression, his appointment of four ministers with a Nazi past to his cabinet, his public quarrel with Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, his decision to close a Jewish refugee transit camp following an Arab terrorist incident near the Slovakian border, and his chilly encounter in Vienna with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir over this explosive matter.

Kreisky was born into a fully acculturated prosperous, and secular Bohemian family. Kreisky’s parents were opponents of Zionism, as were most bourgeois Austrian Jews. His brother, Paul, though, turned to religion and settled in Palestine in 1938.

At the age of 15, Kreisky joined the youth wing of the Socialist Party. In 1935, he was arrested, charged with anti-state activities and imprisoned for 18 months. A few months after Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938, he fled to Sweden, where he earned a living as a journalist and businessman.

Twenty of his relatives were murdered during the Holocaust.

Returning to Austria in 1945, he joined the Austrian foreign service and was posted to Stockholm. In 1951, President Theodor Korner hired him as an advisor. Two years later, he was appointed state secretary in the Foreign Ministry. In 1959, he became foreign minister. Elected as the Socialist Party’s leader in 1966, he formed his first coalition government n 1970, appointing four ministers who had been loyal Nazis. Kreisky believed that former Nazis had to be integrated into Austrian society.

Kreisky’s clash with Wiesenthal, a Holocaust survivor, broke out in 1975, when he revealed that one of the chancellor’s coalition partners, Friedrich Peter, had a Nazi past. The enmity between the pair began several years earlier, when Kreisky disparagingly referred to Wiesenthal as an Ostjude, a pejorative German word for a Yiddish-speaking Jew from Eastern Europe, and when Wiesenthal criticized Kreisky for having invited a few former Nazis to join his cabinet.

Throughout his tenure as a civil servant and a politician, Kreisky supported the notion of Austrian victimhood, which crumbled in 1986 after the election of Kurt Waldheim as Austria’s president. Waldheim, who had been an officer in the German army and the secretary-general of the United Nations, was accused of participating in war crimes, an accusation he denied.

“Waldheim’s presidency was seen by many as a representation of Austria’s unwillingness or inability to confront its role in the Third Reich and produced much international critique,”Ascheim writes.

According to Ascheim, Kreisky regarded regarded his Jewish descent as “a significant part of the structure of my personality.” On another occasion, he said, “My knowledge about Auschwitz is the only thing that connects me, unconditionally, to my Jewish heritage.” Yet he also said, “I don’t allow anyone to consider me as a member of a specific race.”

Ascheim quotes Menachem Oberbaum, an Israeli journalist based in Austria in the 1970s, as saying that Kreisky’s connection to his Jewishness was highly ambivalent. “Kreisky fought fiercely against being labelled as Jewish,” Oberbaum said. But as Kreisky’s close aide, Wolfgang Petritsch, recalled, “What I loved about (him) is that in private conversations and meetings, he was a typical Central European Jew — the way he told jokes, his irony and his intelligence.”

While he may have been conflicted by his Jewishness in a country where antisemitism ran deep, his deepest personal relationships were with Jews. Indeed, his wife, Vera Furth, was Jewish, the daughter of a wealthy entrepreneur in Sweden who had lived in Austria.

Kreisky’s views on Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians were dovish. Long before it was adopted by Western powers, he endorsed a two-state solution. And in his memoirs, he wrote that Israel risked degenerating into a “crusader state” unless it pursued a “good neighborly” policy with respect to the Palestinians.

The seething Palestinian issue dominated headlines in Austria and Israel on September 28, 1973, when two Syrian terrorists affiliated with the Sai’qa terrorist group abducted a policeman and three Russian Jewish immigrants en route to Israel and demanded the closure of a transit camp in Schonau that housed them. Kreisky closed the camp, and the terrorists released the hostages. However, Austria opened a new camp for Soviet Jewish emigrants in Wollersdorf.

As this event unfolded, Golda Meir flew to Vienna in early October to try to dissuade Kreisky from closing Schonau, through which more than 70,000 Soviet Jews had passed between 1965 and 1973.

Meir claimed he had succumbed to terrorism and had brought shame on Austria. Kreisky replied that he had sought to save Jewish lives. When he refused to reopen Schonau, Meir called his behavior antisemitic.

Upon her return to Israel, Meir told reporters at Ben-Gurion Airport that Kreisky did not even offer her a glass of water during their acrimonious meeting. Kreisky insisted he had offered her coffee and cake and deplored her “tactless behavior.”

The Israeli press branded Kreisky as a self-hating Jew and the Knesset condemned his closure of Schonau. Austrians approved of his decision and labelled Israel’s critique as an unjustified attack on Austria.

Israeli government officials were extremely distraught by the incident. When Israel’s ambassador to the United States, Simcha Dinitz, met U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in Washington on the last day of September, a week before the looming Yom Kippur War, he talked about Schonau rather than Syrian army movements on the Golan Heights.

The Schonau incident may well have been organized by the Syrian regime to divert Israel’s attention away from Syria’s war preparations on the Golan. That, at least, is the theory of Shaul Shay, the former director of the Israel Defence Forces’ military history department.

Despite the bad blood between Israel and Austria, Kreisky played a key role in negotiating the release of 20 Israeli soldiers captured by Palestinians during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

Kreisky visited Israel in 1974 and again in 1976, during which he met his nephew, Yossi, who had been a paratrooper in the Israeli army and of whom he was immensely proud.

Nonetheless, Kreisky never wavered in his opinions regarding the Israel/Palestine dispute.

Austria was the first Western state to recognize the PLO. And at Kreisky’s initiative, Vienna, in 1979, would be the first Western capital to host PLO chairman Yasser Arafat.

Kreisky’s supporters think he influenced Palestinians and Arab leaders in favor of coexistence with Israel. Certainly, as Ascheim suggests, he was ahead of his times in his efforts to bring the Palestinian cause to the forefront of global politics.