A sober voice of reason was heard in Lebanon a few days ago, debunking sacred myths and misconceptions about Israel that some Lebanese hold dear.

Sejaan Azizi, Lebanon’s former minister of labor and a leading member the mainly Christian Kataeb Party, conveyed two major truths to his fellow Lebanese citizens: Israel seeks peace with Lebanon and has no territorial claims against it.

“I truly believe, and please trust that I am being honest, that Israel is not plotting to occupy Lebanon, or to expand its own territory by annexing parts of Lebanon,” he said in an interview with the Lebanese news outlet NBN.

With this rapier observation, he rebuked Lebanese who claim that Israel has malevolent designs on Lebanon.

Azizi, a Christian and the former director of the Voice of Lebanon’s news department, pointed out that Israel’s attitude toward Lebanon is transparent. As he put it, “If Israel is going to make peace with the United Arab Emirates, which is far away from Israel, don’t you think Israel would like to make peace with all Arab countries, including Lebanon?”

And in a biting reference to Hezbollah’s destabilizing role in fomenting tensions with Israel and thereby plunging Lebanon into costly wars, he declared, “Even if Hezbollah wants to, we cannot live in a constant state of war.”

And in a reference to the tense period in the early 1980s when the Palestinians shelled Israel from bases in what was then known as Fatahland, Azizi said that Israel would not have invaded Lebanon in 1982 if conditions on the ground had been different.

In his estimation, there would have been no need for Israel to strike had the Lebanese army been deployed near the Israeli border and in Palestinian refugee camps and had the Palestine Liberation Organization refrained from forming a state-within-a-state in Lebanon.

As he succinctly said, “The Palestinians were occupying (Lebanon) when Israel invaded it.”

Touche.

Lebanon, a country torn by two civil wars, has been pushed and pulled into constant conflict with Israel.

Contrary to its national interests, Lebanon was bullied into participating in the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948. The Israeli army captured 15 Lebanese villages near the border, but then withdrew.

Wisely, Lebanon stayed out of the 1967 Six Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

But in the wake of the Six Day War, the Palestine Liberation Organization established bases in southern Lebanon from which to launch terrorist attacks against Israel. The weak Lebanese government, comprised of Muslims and Christians, could not or would not rein in the Palestinians, who were supported by the Baathist regime in neighboring Syria, one of Israel’s arch enemies.

Israel responded with a succession of retaliatory raids, including one targeting Lebanese aircraft at Beirut Airport.

The PLO, then openly dedicated to Israel’s destruction, continued to pummel Israeli settlements from Lebanese territory, triggering sharp Israeli military operations.

Expelled from Lebanon in 1982, in a reprise of its expulsion from Jordan in 1971, the PLO reestablished itself in Tunis. It was supplanted in southern Lebanon by Hezbollah, a Shi’a social, political and military organization backed and financed by Iran.

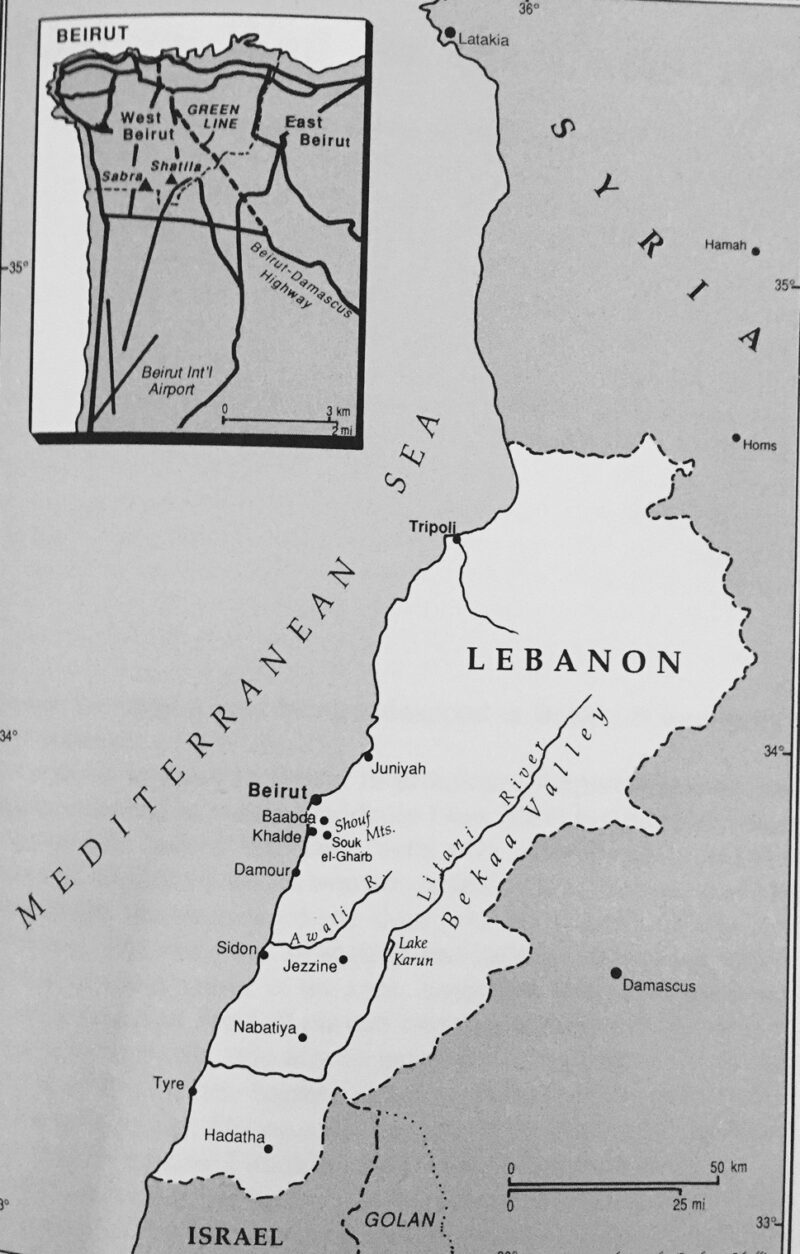

At this juncture, Israel created a security zone in Lebanon north of its border and worked cooperatively with two former Lebanese Christian army officers, Saad Haddad and Antoine Lahad, the commanders of the Israeli-supported South Lebanon Army.

During the early phases of its occupation of Lebanon, Israel was in close contact with the Lebanese Maronite leadership and its armed militia, the Phalange, which committed atrocities in two Palestinian refugees camps, Sabra and Shatila, under the nose of the Israeli army.

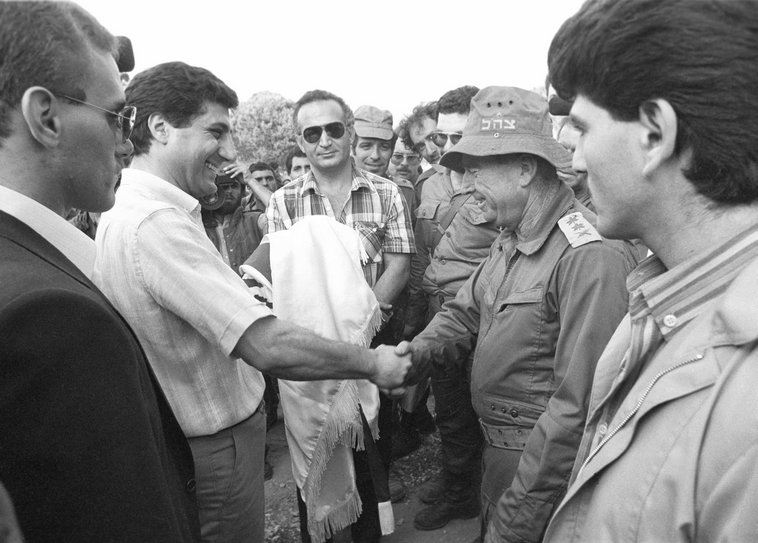

One of Israel’s Maronite allies, Bashir Gemayel, was assassinated by Syrian agents shortly before his inauguration as Lebanon’s president. His brother, Amine, who succeeded him, agreed to honor his brother’s pledge to sign a peace treaty with Israel.

Israeli Middle East experts had predicted that Lebanon would be the second Arab country to forge peace with Israel. Egypt signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1979, the first Arab nation to do so.

On May 17, 1983, Israel and Lebanon signed a peace agreement. The signatories were David Kimche of Israel, Antoine Fattal of Lebanon and Morris Draper of the United States. Under its terms, the state of war between Israel and Lebanon was officially terminated and Israel agreed to pull out of Lebanon.

Meanwhile, the second Lebanese civil war, which had broken out in 1975, raged on. It would not end until 1990.

Lebanon’s peace pact with Israel met with strong opposition from Lebanese Muslims, Syria and the rest of the Arab world. It was formally abrogated by Lebanon in the winter of 1984.

Israel remained in southern Lebanon, but its occupation was fiercely resisted by Hezbollah in a deadly guerrilla war which exacted a toll on Israeli soldiers. When Israel’s army withdrew unilaterally in May 2000, Prime Minister Ehud Barak invited South Lebanon Army personnel to settle in Israel.

Israel’s pullout was regarded by Hezbollah and its patron, Iran, as a victory. Even after the withdrawal, Hezbollah claimed that Israel was still occupying Lebanese land. Mount Dov, or Shebaa Farms, is a small strip of territory on the Golan Heights that Israel seized from Syria in the Six Day War, but that Hezbollah considers sovereign Lebanese territory.

The second war in Lebanon erupted in 2006 after Hezbollah ambushed an Israeli army patrol inside Israel. A battle ensued, resulting in the loss of several Israeli soldiers. Israel’s prime minister, Ehud Olmert, ordered a massive air campaign against Hezbollah missiles and bases. During the last few days of the month-long war, Israel launched a ground offensive in Lebanon.

The war ended on an inconclusive note, but Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah candidly said that, if he known how destructive it would be, he would not have ignited it.

Since then, Israel and Hezbollah have clashed periodically.

Given Hezbollah’s stranglehold over Lebanese politics, it is highly doubtful whether Lebanon will be able to make peace with Israel.

In a 2005, in a Newsweek interview, Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri said, “We would like to have peace with Israel. We don’t want wars. We hope that the peace process moves ahead with us, with the Syrians, with all the Arab countries.”

But he added that Lebanon would not join Egypt and Jordan in signing a separate peace treaty with Israel.

Hariri’s successor, Fouad Siniora, dismissed that possibility altogether, asserting in 2006 that Lebanon would be the “last Arab country to make peace with Israel.”

Last month, Lebanese President Michel Aoun, an ally of Hezbollah, retracted his remark that Lebanon would be open to the idea of peace with Israel if their mutual problems could be solved. “There are many problems, including occupied Lebanese lands and disputed land and sea borders,” he said in a reference to Shebaa Farms and Lebanon’s current maritime dispute with Israel.

Aoun also said that the issue of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon would have to be resolved before Lebanon could consider making peace with Israel.

At present, Israel and Lebanon are embroiled in a conflict over three potentially rich natural gas deposits in the Mediterranean Sea that the United States has been trying to defuse.

On September 9, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs David Schenker conferred with Lebanese leaders in Beirut in an attempt to iron it out. “I believe we are making some incremental progress,” he said, adding that an “absurd” sticking point was still blocking a resolution of the dispute.