During the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Chinese city of Shanghai was home to more Jews than any other metropolis in Asia. Congested, cosmopolitan and utterly exotic, its population exceeded three million, of whom 49,000 were foreigners, including about 20,000 Jews.

Shanghai’s Jewish community was extremely diverse, consisting of Middle Eastern, Russian and Central European Jews. The Arabic-speaking Baghdadi Jews, primarily from Baghdad, Basra and Cairo, mostly arrived in the 19th century. The Russians poured in after the 1920s. The Central Europeans, mainly from Germany and Austria, landed in the 1930s, fleeing fascism and antisemitism.

The history of their respective settlement is recounted in a substantive book of essays, A Century Of Jewish Life In Shanghai, published by Touro University Press and Academic Studies Press. It is edited by Steve Hochstadt, an American historian whose grandparents escaped from Vienna in 1939 and settled in Shanghai before moving to the United States. The essays are taken from a 2015 conference held at the Touro Law Center.

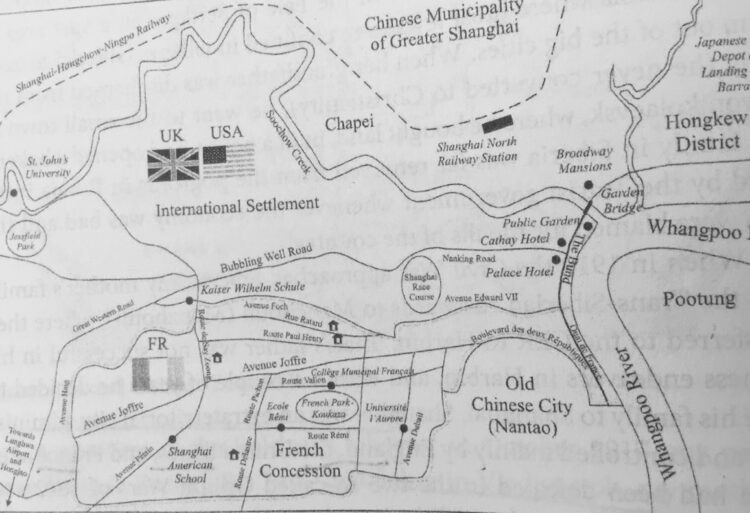

As Hochstadt points out, Shanghai was an extraterritorial city administered mainly by Britain, the United States and France after China had been defeated in the Opium Wars of 1842 and 1860s. The British, along with the Americans and several Europeans, ran the International Settlement. The French were in charge of their own concession. China controlled two districts adjacent to the foreign concessions.

The Chinese neighborhoods fell into the hands of the Japanese army in 1937, leaving the port unmanned and wide open. As a result, migrants without entry documents or work permits could enter the city. Shanghai was thus one of the very few places where Jewish refugees from Europe were allowed in.

On December 8, 1941, a day after bombing the U.S. naval base in Pearl Harbor, Japan seized the International Settlement. Japanese forces maintained the status quo in the French concession due to Vichy France’s alliance with Japan’s ally, Germany.

In 1943, Japan classified all Westerners, apart from Germans, Vichy French and Italians, as “first-class enemy nationals.” Among the British citizens rounded up were 340 Baghdadi Jews, who were interned and whose homes were requisitioned.

During the same year, Japan established a special designated area in a dilapidated part of town known as Hongku. It was reserved for stateless refugees who had lived in Shanghai since 1937. A half mile in length and three-quarters of a mile in width, Hongku was essentially a ghetto. On July 17, 1945, the U.S. Air Force struck a Japanese target in Hongku, accidentally killing 31 Jews in the vicinity.

Although allied with Nazi Germany, Japan did not adopt an antisemitic posture toward Jews in Shanghai. In 1942, a senior Gestapo official who had directed the massacre of Jews in Poland, Colonel Joseph Meisinger, visited Shanghai in the hope of persuading the Japanese authorities to persecute or murder Jewish refugees.

“The Japanese did not appreciate any meddling in their affairs in China, and were also suspicious of their German allies, who had not informed them in advance of their attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941,” says Hochstadt. “Japan was also ill at ease with Aryan racism, since in the Nazi ranking of ethnic groups, Asians were only a few notches above the Jews. Most importantly, Japan had no intention of sharing power in Asia with their German allies.”

Russian nationals, including 5,000 Jews, were not incarcerated by the Japanese because the Soviet Union had signed a neutrality agreement with Japan in April 1941.

Russian Jews began settling in Shanghai in the 1920s. They came from Harbin, a northern Chinese city in Manchuria which until then had the largest Jewish community in the Far East. Following Japan’s offensive into Manchuria in 1931, many more Russian Jews settled in Shanghai, driven out by the antisemitism of White Russians and the uncertain attitude of Japan toward Jews.

The first Jewish refugees from Europe left Germany and Austria starting in 1938. Jews from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Lithuania followed.

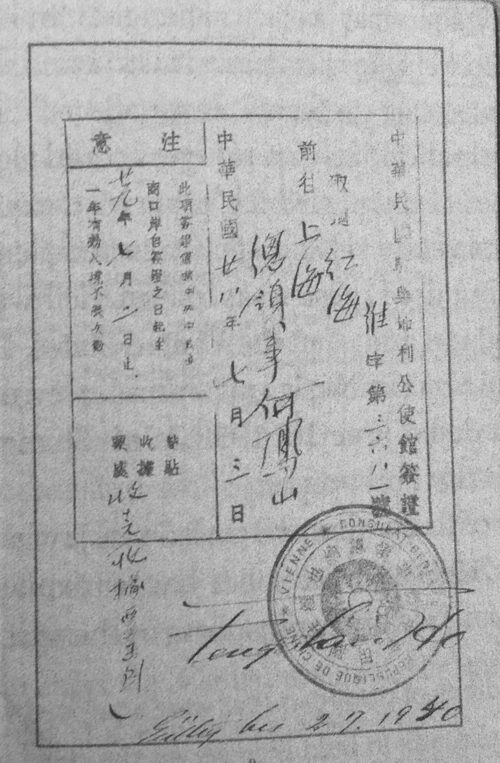

A Chinese diplomat based in Vienna, Feng Shan Ho, assisted Austrian Jews by handing out visas. “The visas were to Shanghai ‘in name’ only,” writes Manli Ho, his daughter. “In reality, they were a means to help Jews to leave Austria and eventually find a way to the U.S., Britain and other preferred destinations.”

By 1940, upwards of 16,000 European Jews had settled in Shanghai. From 1941 onwards, Germany forbade Jews to emigrate as the Nazi regime moved inexorably closer toward a Final Solution of the so-called Jewish question. “The records of Jewish arrivals in Shanghai in 1941 are very sparse, not permitting an estimate of how many landed that year,” writes Hochstadt.

The established Baghdadi community, led by figures such as Sir Victor Sassoon and Lawrence and Horace Kadoorie, helped the new European arrivals with housing, food, jobs and education for their children. But the majority of refugees succeeded in establishing “an independent existence, however precarious.”

Baghdadi Jews, who were originally citizens of the Ottoman Empire, became British subjects and prospered in Shanghai. Among its luminaries were Benjamin David Benjamin, a real estate tycoon, and N.E.B. Ezra, the owner of hotels, factories, cinemas and theaters.

“Members of this community lived in close proximity and were generally either related by marriage or linked commercially,” says Hochstadt.

They mingled with the Chinese elite, but had little social contact with ordinary Chinese people and rarely bothered to learn Mandarin. “In most ways, they adopted the Western sense of social and moral superiority,” Hochstadt notes.

When the war in the Pacific ended, Chiang Kai-shek’s army, along with U.S. forces, seized Shanghai. Shortly afterward, the civil war pitting the Chinese Nationalists against the Communists resumed, with the Communists declaring victory in May 1949.

Most Jews left Shanghai between 1946 and 1948. The rest departed in the years from 1950 to 1952, resulting in the closure of the Ohel Rachel synagogue and the Jewish school.

By then, foreigners had been stigmatized by the new regime as “despised imperialist parasites.” With Western landlords and property owners having been tortured and threatened with death, the Sassoons sold their holdings at bargain basement prices.

Amid the revolutionary fervor, anti-Western feeling took hold of the Chinese populace. Before all these events, as the Chinese scholar Xu Xin writes, “the Chinese and their government were very sympathetic to the sufferings of European Jewry and tried to take actions to assist them.”

Hochstadt left Shanghai in April 1951, two years after his mother’s departure. His father joined him in the United States a year later.

And so a unique chapter in Shanghai’s storied history ended.