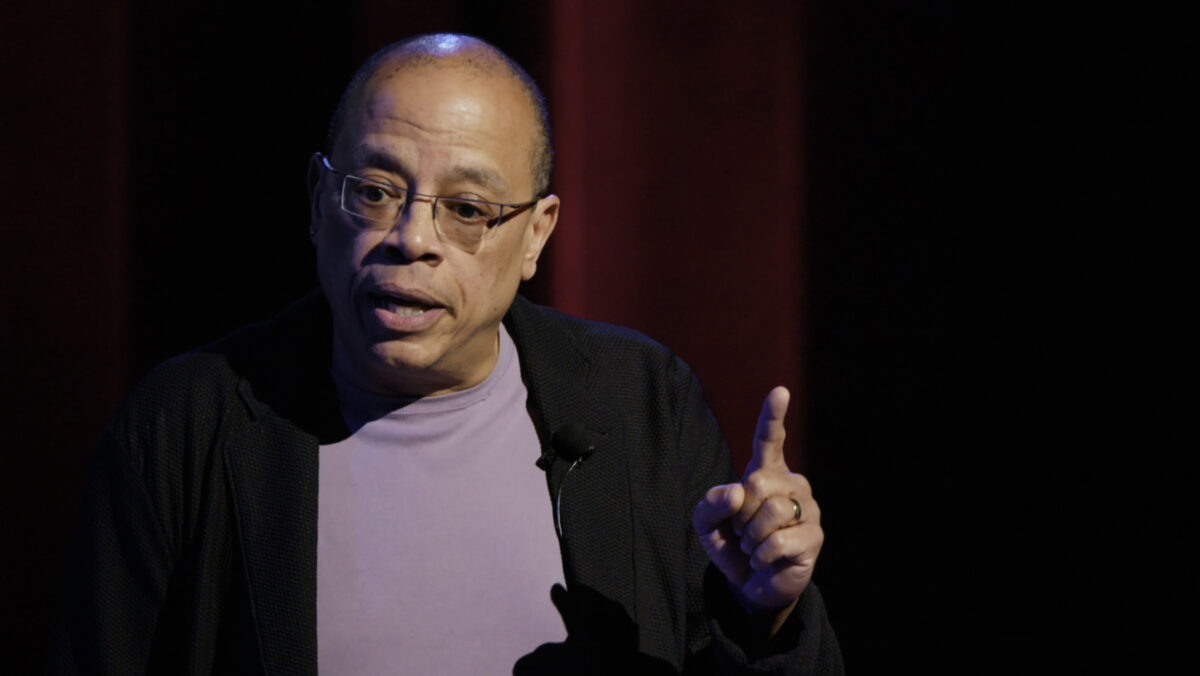

Jeffery Robinson, the writer and narrator of Who Are We: A Chronicle of Racism in America, does not mince words.

“America is one of the most racist countries on earth,” he says in the first few minutes of this hard-hitting documentary, which opens in Toronto on February 4. Elaborating on this claim, he contends that the United States was founded on the principle of white supremacy.

Robinson, a graduate of Harvard University and the former deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union, issues a scathing indictment of his country in this searingly unsparing film, directed by Emily and Sarah Kunstler.

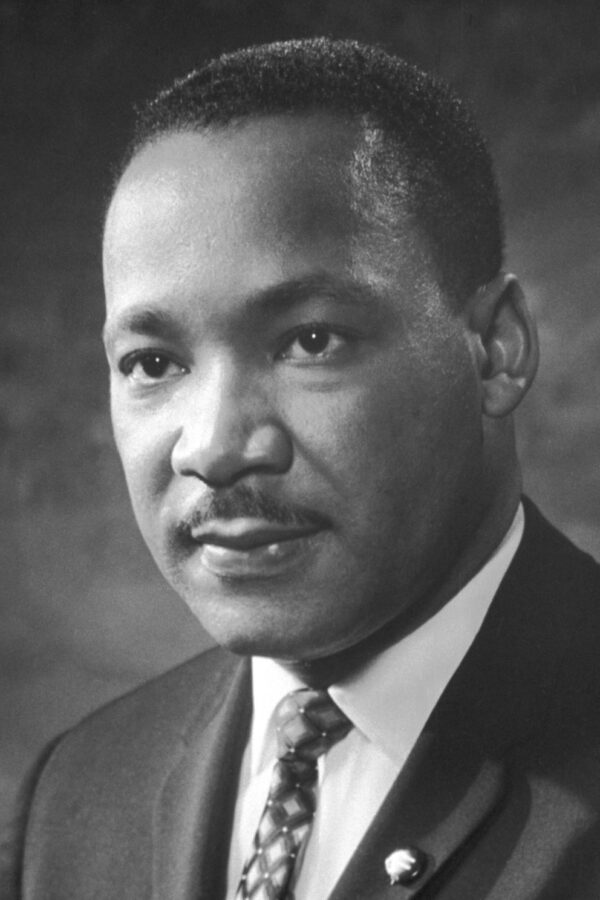

He begins his inquiry in his hometown, Memphis, Tennessee, where civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968. His assassination was clearly a setback for the cause of racial equality in America, he suggests.

Historically speaking, he goes on to say, race relations in America have oscillated. For every step forward, there have been two steps backwards.

Americans are proud of their democracy, yet loathe to admit the obvious. For hundreds of years, American democracy was the exclusive preserve of whites at the expense of blacks.

And although the U.S. Civil War ended more than 150 years ago, some Southerners still cling to the misguided notion that it was not about slavery. This theme emerges in a futile conversation Robinson conducts with a Southern man standing in front of a Confederate monument in Charleston, South Carolina.

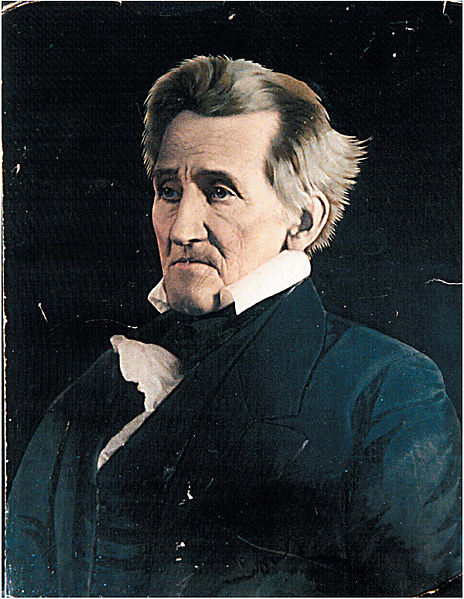

Robinson contends that racism is so deeply entrenched that Americans sometimes fail to recognize its existence. How many Americans know, much less care, that the U.S. president who graces the $20 bill, Andrew Jackson, was an unabashed slave owner?

Indeed, 12 American presidents, including the first one, George Washington, were slave holders. None of them had a problem with white supremacy, Robinson says.

Nor did Frances Scott Key, a slave owner and the composer of The Star-Spangled Banner, the U.S. national anthem, whose third verse disparages blacks.

In this wide-ranging film, Robinson provides viewers with a potted history of American segregationist practices and interviews African Americans whose family members have been victimized by racism.

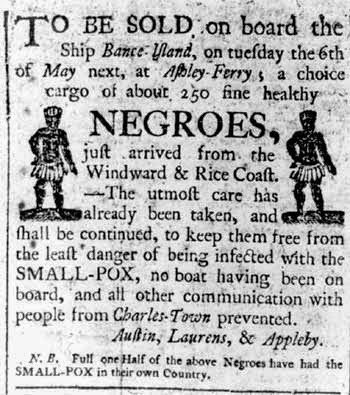

He tells us that the first slaves arrived in 1619, and that the first American slave ship, the Desire, set sail for Africa in 1636. He discloses that Virginia passed a law in 1662 to ensure that the children of slaves, sometimes fathered by white slave owners, would be slaves themselves.

He reminds us that cotton, the chief U.S. export until the early 20th century, was planted and harvested by slaves and indentured workers. He informs us that the modern-day police department, especially in southern states, was originally formed to catch runaway slaves.

The gains of Reconstruction, during which 2,000 African Americans served in elective offices, were rolled back by the Southern states in complicity with Northern states. He glosses over the 1896 Plessy vs. Ferguson U.S. Supreme Court decision, which ratified the separate-but-equal doctrine to enforce segregation in public places.

He says that Confederate monuments and statues began appearing in the early 20th century to honor Confederate heroes such as Robert E. Lee and Nathan Bedford Forrest, a founder of the Ku Klux Klan. He reminds us that one of the first movies screened at the White House, The Birth of a Nation (1915), was steeped in racist tropes and stereotypes. He laments that not a single perpetrator was charged with a criminal offence following the anti-black pogrom in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921.

In Selma, Alabama, Robinson stands near the Edmund Pettis bridge, which was named after a U.S. senator and grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan.

Contemplating the future of race relations, he cites the 1968 Kerner Report, which warned that the United States might well degenerate into a dual society based on color.

Robinson compares Black Lives Matter to the civil rights movement of the past. And in a personal note, he tells us that his parents were only able to buy a house in a white neighborhood in Memphis due to the efforts of a Jewish real estate agent.

Robinson paints an unremittingly dark picture of race relations America, but in doing so he neglects to mention the abolitionist movement or the white politicians who have fought for the rights of African Americans.

In a poignant scene, though, he tries to strike a balance between hope and despair when he and two white school mates reminisce about their past at a Catholic school in Memphis.

At the end of the day, though, race is still an unfinished business in the United States. As Martin Luther King Jr. said a year before he was murdered, “We still have a long, long way to go.”

Ultimately, this is the sober message of Who Are We: A Chronicle of Racism in America.