The world’s oldest, most persistent hatred is expertly surveyed in a two-hour documentary by Ilan Ziv. His movie, Antisemitism, will be screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from October 22 to November 1.

Ziv’s substantive film covers a wide swath of ground, but focuses on France, whose treatment of Jews has been stunningly ambivalent since the French Revolution.

The opening scene sets the tone. “Beat it, Jews,” neo-Nazi thugs bellow in a street demonstration in a French city. “France isn’t yours.”

Jews in France were emancipated in 1791, the first in Europe to be unshackled from their chains. From that point forward, French citizenship was no longer defined by race and religion. But a little more than a century later, France descended into antisemitic purgatory when the Jewish artillery army captain Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of treason.

The Dreyfus affair, a conservative assault on the liberal republic, lasted from 1894 until Dreyfus’ exoneration in 1906. It divided the country into two warring camps, and was a prelude the fascist, pro-German Vichy regime that persecuted French Jews and deported foreign-born Jews to Nazi extermination camps.

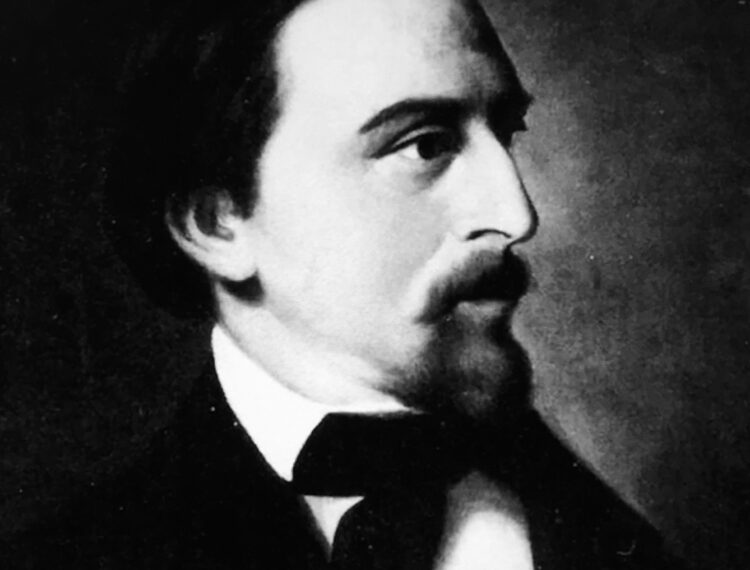

As Ziv suggests, one of Vichy’s ideological godfathers was the reactionary journalist Eduard Drumont, whose rag, La Libre Parole, was the first major newspaper in France to promote antisemitism unabashedly. To Drumont, Jews represented modernity, capitalism and liberalism and posed a clear and present threat to French Christianity.

Yet it was a late 19th century German antisemite, Wilhelm Marr, who coined the word antisemitism. He defined Jews as a race and branded them as a foreign body in German society, an idea the Nazis would incorporate into their racist ideology.

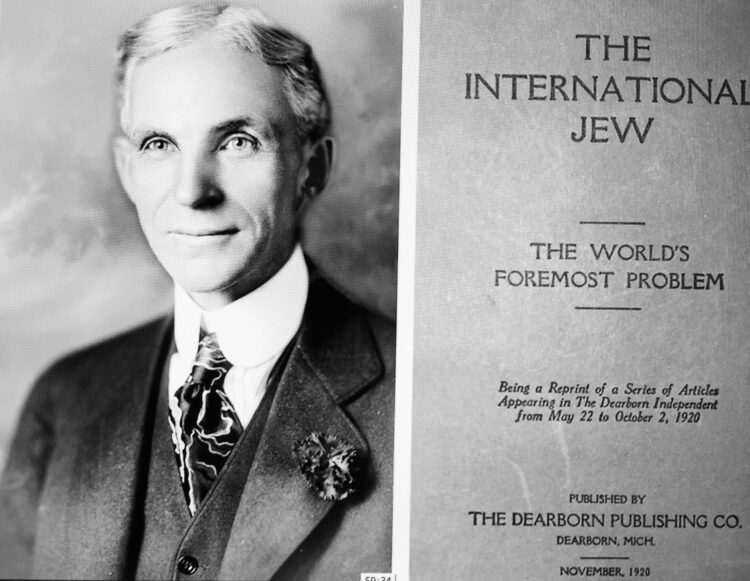

Henry Ford, the American industrialist, promoted the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a czarist forgery claiming that Jews sought global domination. Ford, whose admirers included Adolf Hitler, published excerpts of the Protocols in his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent.

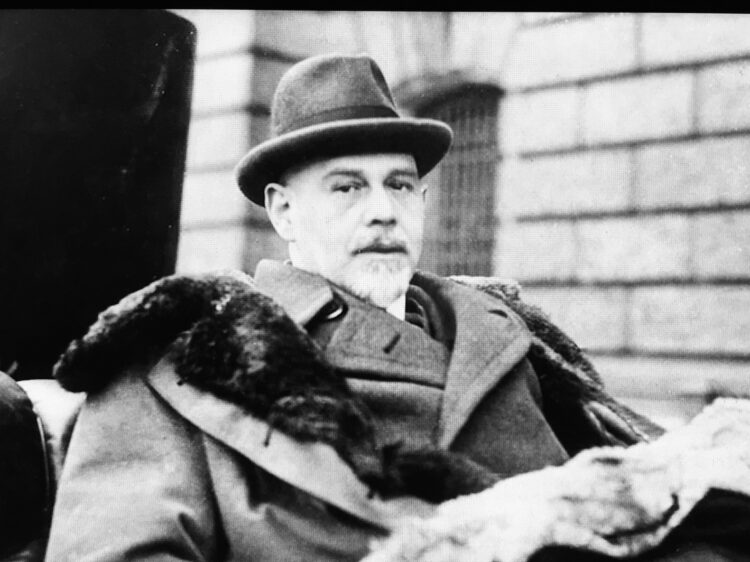

Walther Rathenau, the short-lived foreign minister of Germany in the early 1920s, was assassinated by right-wing radicals who had been heavily influenced by the Protocols. They believed he was a member of a secret Jewish cabal responsible for Germany’s economic and political woes.

Ziv correctly contends that Holocaust denial is another form of antisemitism. One of the deniers he cites is Darquier de Pellepoix, a Vichy official who was in charge of the persecution of Jews. “At Auschwitz, they only gassed lice,” he told a reporter in a contemptuous dismissal of Jews.

Jean-Marie Le Pen, the former leader of the far-right National Front, gained notoriety when he claimed that the Nazi gas chambers were merely a “detail” in history.

The postwar influx of Muslims into France, combined with the emergence of the Arab-Israeli conflict, created deep-seated antisemitism in the Muslim community, Ziv says.

As he points out, the Muslim comedian Dieudonne has ridiculed the Holocaust and incited racial animosity. Mohammed Merah, an Islamic State acolyte, murdered several Jewish schoolchildren in Toulouse.

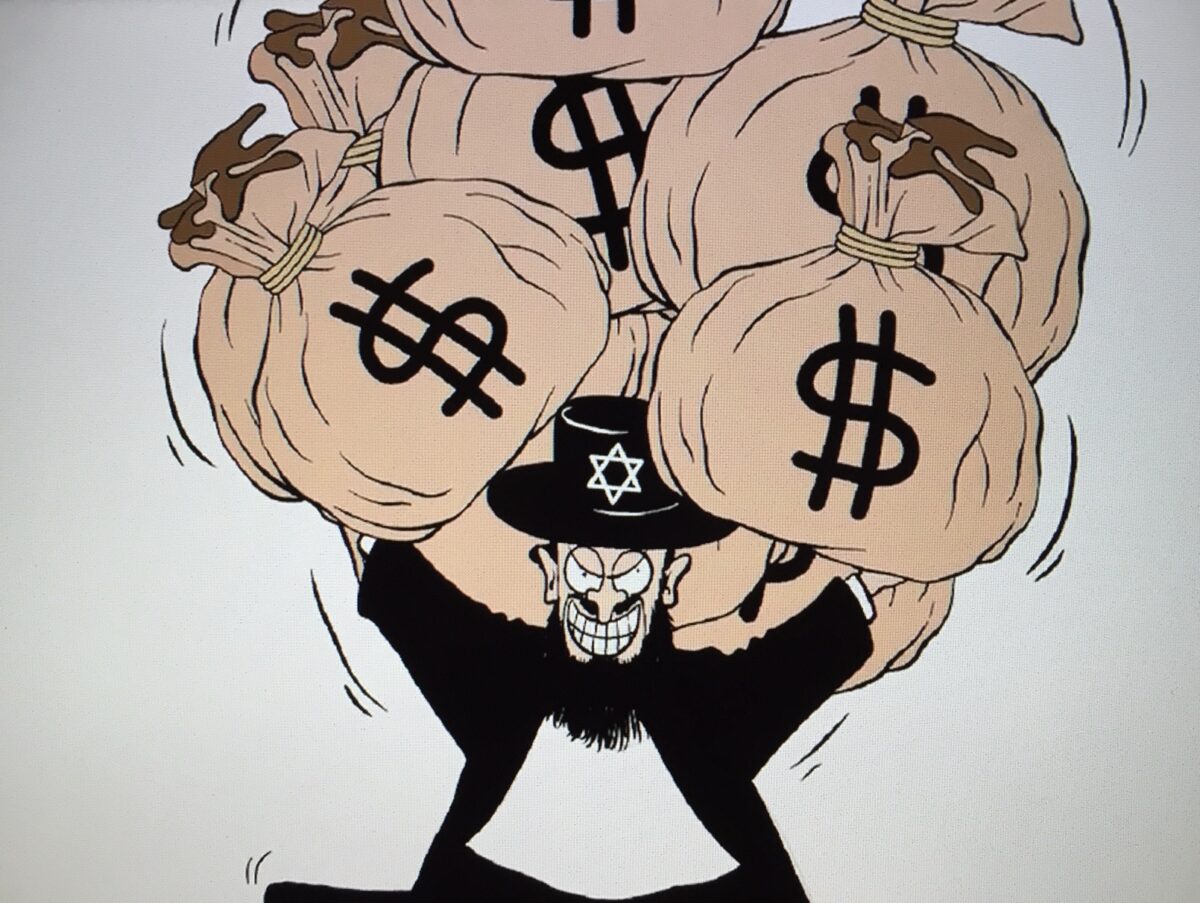

Two French Jews, Ilan Halimi and Mireille Knoll, have been murdered by Muslims in recent years. To their blinkered assassins, they were symbols of Jewish wealth.

Such is the atmosphere in France today that armed guards must be posted in front of synagogues, a common enough phenomenon in other European countries too.

This “abnormal reality” has become the new norm, laments a French rabbi, distilling the essence of our troubled times.