On June 14, 1940, on the very day German troops marched triumphantly into Paris, a freelance journalist named Rosie Goldschmidt Waldeck checked into the swankiest hotel in Bucharest, the Athene Palace. She remained there for the next six months, watching events unfold in Rumania, a neutral and deeply divided Balkan country whose natural resources were coveted by Germany on the eve of its disastrous invasion of the Soviet Union.

Waldeck, a German Jew who had immigrated to the United States in the 1930s and who wrote for American and Canadian publications, was a keen observer of the Rumanian scene, which was in a constant state of flux.

A convert to Christianity, she covered epic upheavals in Rumania — the abdication of a reigning king, the Soviet seizure of territory Rumania had acquired in World War I, antisemitic pogroms perpetrated by the Iron Guard fascist movement and the budding alliance between Rumania and Nazi Germany.

Waldeck’s pungent observations are contained in a highly readable book, Athene Palace: Hitler’s “New Order” Comes To Rumania, which was originally published in 1942 and has now been reprinted by The University of Chicago Press, with a new foreword by the American journalist Robert Kaplan.

One might ask why a contemporary reader would bother with a book so old and outdated. The answer is clear. First, Waldeck is an uncommonly talented writer whose prose is a pleasure to read. Second, she writes authoritatively. Rumania lay on the fault line between Allied and Axis powers and was up for grabs, and Waldeck understood the dynamics of this power struggle, which would dramatically alter the geopolitical landscape of Europe, at least temporarily.

She was wise to book a room at the Athene Palace, one of Europe’s grand hotels and just across a plaza from King Carol II’s palace. Diplomats, spies, military attaches, generals, Rumanian politicians, German and Italian ministers, newspaper reporters, businessmen and mink-clad Rumanian beauties mingled in the lobby, trading information and secrets, gossiping and angling for the latest news.

The denizens of the hotel that most captivated Waldeck were, as she puts it, the Old Excellencies, the gaggle of former Rumanian cabinet ministers, diplomats and generals who appeared at their favorite tables in the lobby before noon, ordering lunch, drinking Turkish coffee and commenting on “everything in sight,” particularly the fairer sex. “For no matter what had been their political position, (their) real life work had always been to be charming to women with but one purpose in mind, and their successes were legendary and to many enviable.”

Rumania, in 1940, was militarily vulnerable. With the German conquest of France, its ally and protector, Rumania had much to fear. Hungary, Bulgaria and Russia, having lost 60,000 square miles of land to Rumania in the last world war, were eager to pounce and regain it. Germany, meanwhile, hungered for Rumania’s wheat, oil and friendly neutrality, while the Allies worked to block German ambitions.The Rumanians, of course, sought to maintain their independence within the framework of Greater Rumania.

King Carol II, a great grandson of Britain’s Queen Victoria, tried to be all things to all men, playing one side against the other in order to preserve Rumania’s territorial integrity and his throne. But with France’s ignominious defeat, he was no longer able to play what Waldeck describes as “his beautifully ambiguous game.”

Southern Europe and Rumania in particular, were now at the mercy of Germany. “Hitler alone could stop the Russians, Bulgarians, Hungarians from falling on Rumania. If Hitler wanted to stop them.”

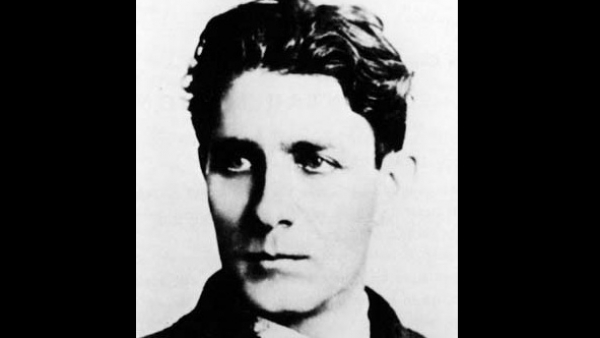

Domestically, the challenge that King Carol II faced was embodied in the person of a young and dynamic lawyer, Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, the founder and leader of the green-shirted Legion of the Archangel Michael, or the Iron Guard. Banned in 1933, the Iron Guard roared back soon afterward, becoming the second strongest political party after the 1937 election. Ironically, the Iron Guard was funded, in part, by the Jewish industrialist Max Ausschnitt, who had been intimidated into becoming its patron and banker.

Worried by Codreanu’s growing success, King Carol II, in 1938, decided to steal his thunder. He dissolved all political parties, established a royal dictatorship and arranged his murder. As Waldeck notes, Hitler, in his only meeting with King Carol II, tacitly encouraged him to rid Rumania of Codreanu.

Codreanu, however, was not his sole problem.

Much to Rumania’s shock and consternation, the Russians suddenly demanded the return of Bessarabia and Bukovina. Rumania turned to Germany for sympathy and assistance. Hitler, who had signed a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union in 1939, advised King Carol II to cede the provinces to the Russians. After the war, Hitler promised, he would try to convince Moscow to hand them back to Rumania.

As expected, Rumania’s docility whetted Hungary’s and Bulgaria’s appetite for Transylvania and Dobrudscha, which Rumania had grabbed. In this case, too, Hitler declined to intervene on Rumania’s behalf.

Waldeck skillfully navigates the shoals of Rumania’s foreign policy, but her mastery of its Byzantine internal intrigues is second to none.

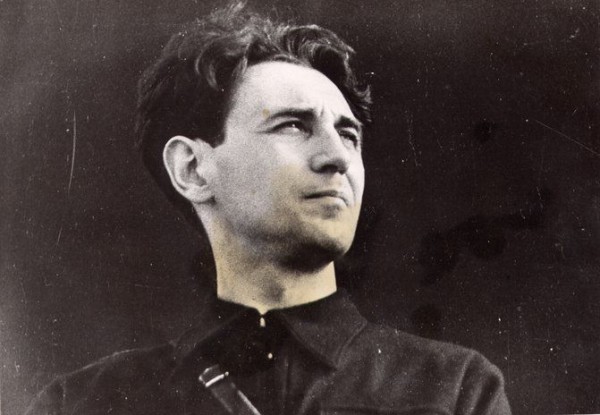

She focuses a good deal of her attention on Ion Antonescu, an army general whom Germany respected. From 1940 onward, he played a decisive role in Rumanian politics, either behind the scenes or at its very center.

Antonescu supported the promulgation of a series of decrees that excluded all Jews from the press, theater and management of big businesses. “In Rumania, antisemitism was a very old story,” Waldeck writes. “Even the liberals of the 19th century … pursued an antisemitic policy.” She adds, “This antisemitism was the reaction to the fact that the Jews had succeeded in forming the middle class … and in creating the only bourgeoisie in Rumania.”

Under pressure from the Allies after World War I, Rumania granted full civil rights to Jews. From that moment on, antisemites like Codreanu and his mentor, Alexandru Cuza, fought to turn back the clock. They were particularly incensed that King Carol II had left his wife, the queen, for the Jewish-born Elena Lupescu, whose maternal grandfather was a Bessarabian rabbi.

When King Carol II abdicated, he was succeeded by his teen aged son, Michael. But real power lay elsewhere. Antonescu, in tandem with the Iron Guard’s new leader, Horia Sima, effectively ruled Rumania.

A vicious antisemite, Sima preferred a radical solution to the so-called Jewish problem. Antonescu, with his fear of violence, proposed a compromise: antisemitic legislation that would eliminate Jews from the economy. Ironically, Germany was dismayed by its disruptive effect on the Rumanian economy.

Not content with these draconian measures, the Iron Guard imposed a reign of terror on the Jewish community, looting Jewish homes, confiscating Jewish-owned shops and kidnapping and killing Jews. Antonescu, who valued law and order, was appalled, Waldeck claims.

With Germany’s consent, Antonescu dismissed high-ranking Iron Guard officials in the government. In what Waldeck mildly calls a “gesture of protest,” Guardists launched a savage pogrom, directing their animus at several hundred wealthy Jews whom they accused of treason.

“Many were dragged to a slaughterhouse where they were mutilated, killed and then hung up like hogs, while a large sign marked them Kosher Meat,” she writes chillingly.

The Guardists then proceeded to set fire to synagogues and rape Jewish women in front of their husbands.

Apparently sickened by this obscene rampage, Antonescu ordered the dissolution of the Iron Guard. Now he was the sole master of Rumania. Under his administration, Rumania joined the Axis powers, fought alongside Germany and wrested back Bessarabia and Bukovina. And in Rumanian conquered Transistria, Antonescu presided over the murder of tens of thousands of Jews during the Holocaust, a bloody chapter that occurred after Waldeck left Bucharest in January 1941.

In Athene Palace, she documents all these momentous developments with skill and panache, giving a reader an insider’s view of a nation and a people in turmoil and transition.