It’s the end of the year and the holiday season is upon us. Curl up in a comfortable chair or couch and enjoy these books for your reading pleasure.

James Lacey’s Great Strategic Rivalries From The Classical World to the Cold War (Oxford University Press) delves into the geopolitical conflicts that have engaged major powers since the ancient rivalry between Athens and Sparta. The thoughtful essays in this massive volume, written by a coterie of scholars and edited by Lacey, bring to life rivalries that pitted city states, countries and empires against each other: Rome versus Carthage, England versus France, Genoa versus Venice, the Ottomans versus the Habsburgs, Britain versus Germany, Russia versus Germany, the United States versus Japan, and the United States versus China and the Soviet Union.

Krishna Kumar, in Visions of Empire: How Five Imperial Regimes Shaped the World (Princeton University Press), draws penetrating portraits of five empires — Ottoman, Habsburg, Russian/Soviet, British and French — and their leaders and explains how they differed from nation states.

In Stalinist Perpetrators on Trial: Scenes from the Great Terror in Soviet Ukraine (Oxford University Press), Lynne Viola, a professor of history at the University of Toronto, tells the untold story of the perpetrators of Joseph Stalin’s bloody purge in the Ukraine. In what has been called “the purge of the purges,” almost 1,000 members of the secret police were charged with violating Soviet law. Viola, in this impassioned book, takes a reader into the darkest recesses of Stalin’s repressive universe.

During World War II, Britain’s Special Air Service, known as the SAS, pioneered a form of guerrilla combat that has since become a centrally component of modern warfare. In Rogue Heroes (McClelland & Stewart), a fast-paced authorized history, Ben Macintyre, a British journalist, describes the origins and evolution of this secretive unit, which was disbanded in 1945 and reestablished just two years later.

Ben Bradlee was the executive editor of The Washington Post when two of its reporters, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, changed the course of American history by uncovering the Watergate scandal. This was the high point of Bradlee’s storied 45-year career in journalism, which Jeff Himmelman describes at length and in voluminous detail in Yours in Truth (Random House), a book to be savored especially by news junkies. In addition to delving into his career as a reporter and editor, Himmelman discusses his relationships with movers and shakers and his views on the role of journalism in a democratic society.

Hundreds of books have been written about Jews and Judaism, but in The Origin of the Jews: The Quest for Roots in a Rootless Age (Princeton University Press), University of Pennsylvania scholar Steven Weitzman skillfully traces the history of the different approaches that have been applied to this question, including archeology, psychology, sociology and linguistics.

The Book of Samuel is one of the supreme achievements of biblical literature. In The Beginning of Politics: Power in the Biblical Book of Samuel (Princeton University Press), Moshe Halbertal and Stephen Holmes deftly examine the story of Israel’s first two kings, Saul and David, to explore the nature of power.

Tony Michael’s Jewish Radicals: A Documentary History (New York University Press) explores the intertwined histories of Jews and the American Left through a series of thought-provoking essays. Topics run the gamut from building communism in Ukraine to Leon Trotsky’s sojourn in New York City in 1917.

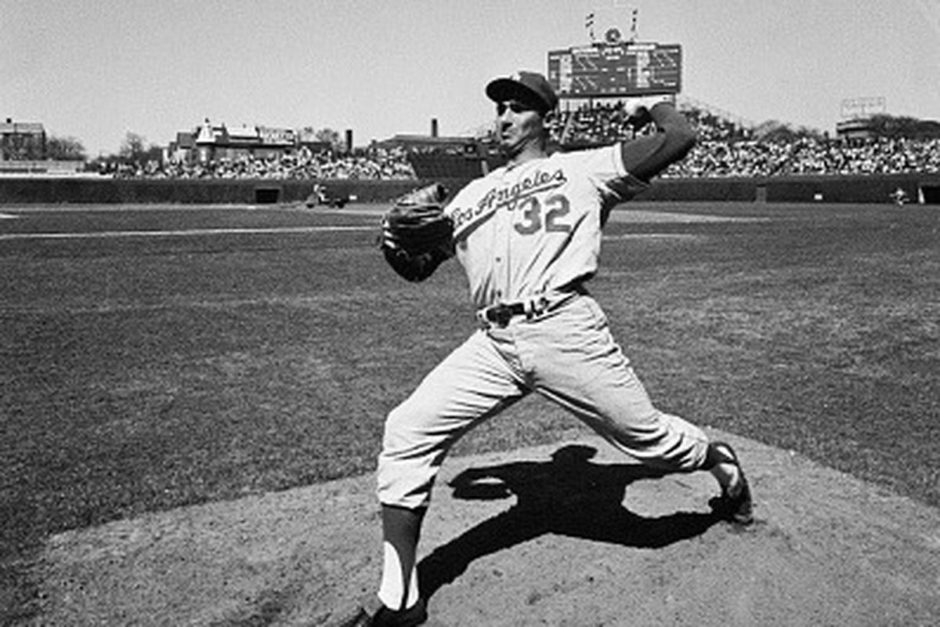

David Kaufman, in Jewhooing the Sixties: American Celebrity and Jewish Identity (Brandeis University Press), takes a long, hard look at the American Jewish relationship to celebrity through four famous Jewish Americans — the baseball star Sandy Koufax, the comedian Lenny Bruce, the folksinger Bob Dylan and the singer Barbra Streisand. He investigates their rise to fame, the brand of Jewishness they represented, and how their fans perceived their identity as Jews.

Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man elected to public office in California, is the subject of Lillian Faderman’s biography, Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death (Yale University Press). The latest in its Jewish Lives series, this fascinating book recounts Milk’s extraordinary journey from a U.S. Navy deep sea diver and Wall Street securities research analyst to his position as a member the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

Harvey Milk in 1978

This year marked the 70th anniversary of two momentous events — the birth of the state of Israel and the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In Rooted Cosmopolitans: Jews and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century (Yale University Press), James Loeffler, a professor of history and Jewish studies at the University of Virginia, charts the intriguing connection between Zionism and the origins of the international human rights movement. An eye opener.

Joseph Suss Oppenheimer, better known as Jew Suss, is one of the most iconic figures in the annals of antisemitism. Remembered today mostly through a vicious 1940 antisemitic film about him made by Nazi Germany, he was the court Jew –personal banker and advisor — to Carl Alexander, the duke of the small German state of Wurttemberg. His meteoric rise and fall is meticulously charted by Yair Mintzker in The Many Deaths of Jew Suss: The Notorious Trial and Execution of an Eighteenth-Century Court Jew (Princeton University Press). “It is no exaggeration to say that ‘Jew Suss’ is to the German collective imagination what Shakespeare’s Shylock is to the English-speaking world,” he says in this richly scholarly work.

Writing on a virtually unknown chapter in the history of Jews in German lands, Hebrew University historian Aya Elyada explores a unique phenomenon in A Goy Who Speaks Yiddish: Christians and the Jewish Language in Early Modern Germany (Stanford University Press) — Christian interest in and engagement with Yiddish language and literature from the 16th to the 18th century. As she observes, “Christian concern with Yiddish should be seen on the one hand as part of a wider interest in Jews and Judaism in early modern Germany, and on the other hand as part of a general interest in questions relating to language and linguistics at the time.”

Antisemitism masquerading as anti-Zionism has emerged in Muslim communities in western Europe in the past two decades. Gregg Rickman, the United States’ first special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism, discusses this contemporary issue in Hating the Jews: The Rise of Antisemitism in the 21st Century (Academic Studies Press), a sober work that leaves a disquieting impression.

Jack Kuper’s affecting memoir, Child of the Holocaust: A Jewish Child in Christian Disguise (Penguin Random House), was originally published in 1967. Translated into several languages, it has been continuously in print since then. The latest edition, due to go on sale next month, may well interest a new generation of readers who know little, if anything, about the Holocaust in Poland, a catastrophe that almost wiped out a venerable and vibrant Jewish community.

Jack Hersch’s Death March Escape: The Remarkable Story of a Man who Twice Escaped from the Holocaust (Frontline Books), is about a Holocaust survivor, Dave Hersch, who twice escaped two death marches toward the close of World War II. The author, the son of the survivor, rightly regards his late father as a true hero.

Julija Sukys’ Lithuanian grandparents, Anthony and Ona, were separated by Red Army soldiers during the last world war and did not see each other for 25 years. When Sukys, a professor of creative writing at the University of Missouri, began writing about them, she discovered a Holocaust-era secret — a family connection to the murder of 700 Lithuanian Jews. The person in charge of this genocidal operation was her grandfather. In Siberian Exile: Blood, War and a Granddaughter’s Reckoning (University of Nebraska Press), Sukys weaves together these separate strands of narrative courageously and movingly.

Robert Gellately, an expert on Nazi Germany, has written a very useful primer on this topic. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Third Reich (Oxford University Press) consists of 10 deeply informative essays on all its aspects. Gellately’s bracing introductory essay is followed by excellent essays on the Weimar Republic, the Nazi seizure of power, architecture and the arts, photography and cinema, the economy, the Holocaust, Germany’s war in Europe, the home front and Germany’s ignominious downfall.

During the Nazi interregnum in Germany, antisemitic Protestant theologians redefined Jesus as an Aryan and Christianity as a religion at odds with Judaism. In 1939, they established the Institute for the Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life, which became the leading propaganda organ of German Protestantism. Susannah Heschel, in The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany (Princeton University Press), expertly examines the institute’s role in fostering a nazified form of Christianity that placed antisemitism at its core.

Israel was conceived by its Zionist founders as a state that would be both exceptional and normal. But none of them, socialists and religious Zionists, could agree on what kind of a country Israel should be. Their clash of visions would have a defining impact on Israeli society. Michael Brenner, a German scholar, grapples with these complex issues in an exemplary book, In Search of Israel: The History of an Idea (Princeton University Press).

Gil Troy, a McGill University historian, sets out the main Zionist schools of thought in a superb anthology, The Zionist Idea: Visions for the Jewish Homeland — Then, Now, Tomorrow (The Jewish Publication Society). He examines the pioneers of political Zionism, Labor Zionism, Revisionist Zionism, Religious Zionism, Cultural Zionism and Diaspora Zionism and prints illuminating excerpts from their works. Troy’s book belongs in any good home library.

Nathan Birnbaum, who coined the word Zionism, was one of the most seminal figures in the pantheon of Zionism. A secular Jewish nationalist who turned toward religious orthodoxy, he left a lasting imprint on the Zionist movement. Jess Olson’s work, Nathan Birnbaum and Jewish Modernity: Architect of Zionism, Yiddishism, and Orthodoxy (Stanford University Press), is an important contribution to the field.

In State of Terror: How Terrorism Created Modern Israel (Olive Branch Press), Thomas Suarez, an anti-Zionist writer based in London, claims that ethno-nationalist Zionists illegally expropriated Arab lands in Palestine by means of terror to establish a “settler state.” He maintains that their use of terror was planned and deliberate. Contending that the Palestinians have been dealt an enormous injustice, he says the Arab-Israeli dispute cannot be resolved on the basis of “genetic entitlement.”

Asmaa al-Ghoul, a Palestinian journalist and human rights activist living in France, and Selim Nassib, a Lebanese journalist based in Paris, deal with a variety of current Middle Eastern issues in A Rebel in Gaza: Behind the Lines of the Arab Spring, One Woman’s Story (Doppel House Press). In particular, they comment on the dire situation in the Gaza Strip and Israel’s armed confrontation with Hamas, which has ruled Gaza for the past 11 years.

Salim Yaqub, a professor of history at the University of California, provides a fresh perspective of U.S. policy in the Middle East in Imperfect Strangers: Americans, Arabs, and U.S.-Middle East Relations in the 1970s (Cornell University Press). Yaqub’s reach is wide. Among the topics he tackles are the Nixon administration’s handling of the Arab-Israeli conflict, Henry Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy in the wake of the Yom Kippur War, the American role in Lebanon’s civil war, and Jimmy Carter’s attempts to reconcile Israel with Egypt. Yaqub’s nuanced knowledge of the region is impressive.

Carter Malkasian, a former U.S. State Department official, has written a comprehensive account of the chaos that has enveloped Iraq in recent years. In 2007, U.S. troops defeated Al Qaeda in Anbar province in what came to be known as the Anbar Awakening. But seven years later, Islamic State obliterated American gains there. In 2017, however, Iraqi, Iranian and U.S. forces virtually evicted Islamic State from its positions in Iraq. Malkasian’s conclusion in Illusions of Victory: The Anbar Awakening and the Rise of Islamic State (Oxford University Press) is that American counter-insurgency techniques cannot change foreign societies and cultures, and that U.S. military intervention always carries a potential for further instability.