Avida Livny’s Israeli documentary, A Deal With the Devil,? delves into one of the most controversial chapters of the Zionist movement in British Mandate Palestine.

It will be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 5-15.

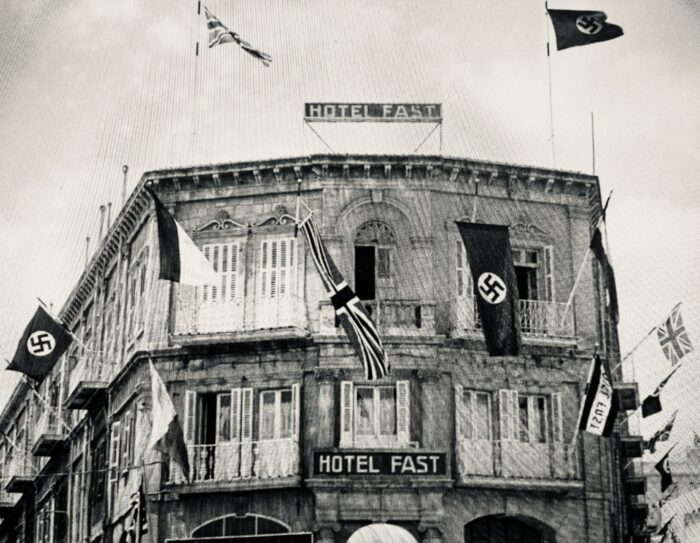

In August 1933, seven months after Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor of Germany, the Anglo-Palestine Bank, the German Zionist organization and Nazi Germany’s Ministry of Economics signed the Transfer, or Havaara, agreement.

Some Zionists hailed it as landmark deal that would benefit the Jewish community in Palestine. Still others condemned it as a sellout to a vicious antisemitic regime.

As Livny explains in the opening moments of his generally absorbing film, the agreement was linked to the Nazi takeover of Germany. The Nazi regime wanted Jews to leave without their assets. German Jews who sought to flee would not emigrate without them.

This impasse was resolved by an ingenious arrangement.

Jews who had decided to settle in Palestine would deposit a percentage of their funds into a special bank account in Germany. Once in Palestine, they could withdraw them to purchase German-made goods.

To its supporters, the agreement was a blessing. It allowed tens of thousands of German Jews to leave a country that had reduced them to second-class citizens and to start their lives anew in the ancestral homeland of the Jewish people. To the Nazis, it conformed with their objective of driving Jews out of Germany.

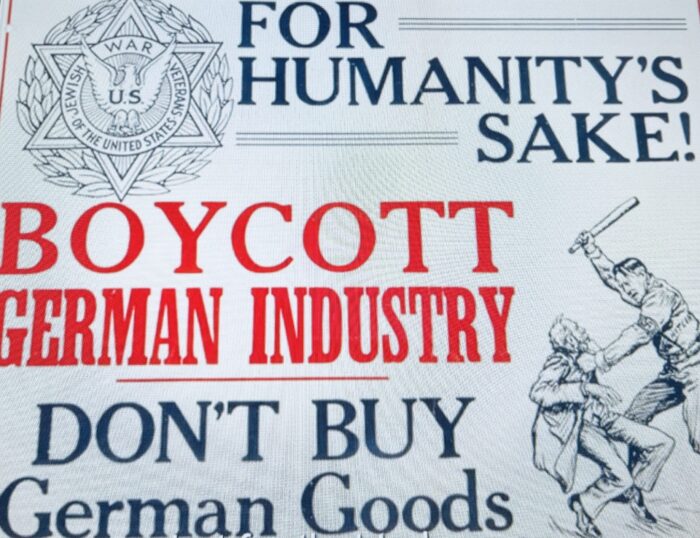

Its outspoken critics in Palestine and abroad despised the agreement, calling it shameful and accusing its organizers of undermining efforts to boycott Germany’s economy.

This footnote in Zionist history has been the object of a succession of monographs and books, some of which have harshly attacked Zionists who favored the agreement.

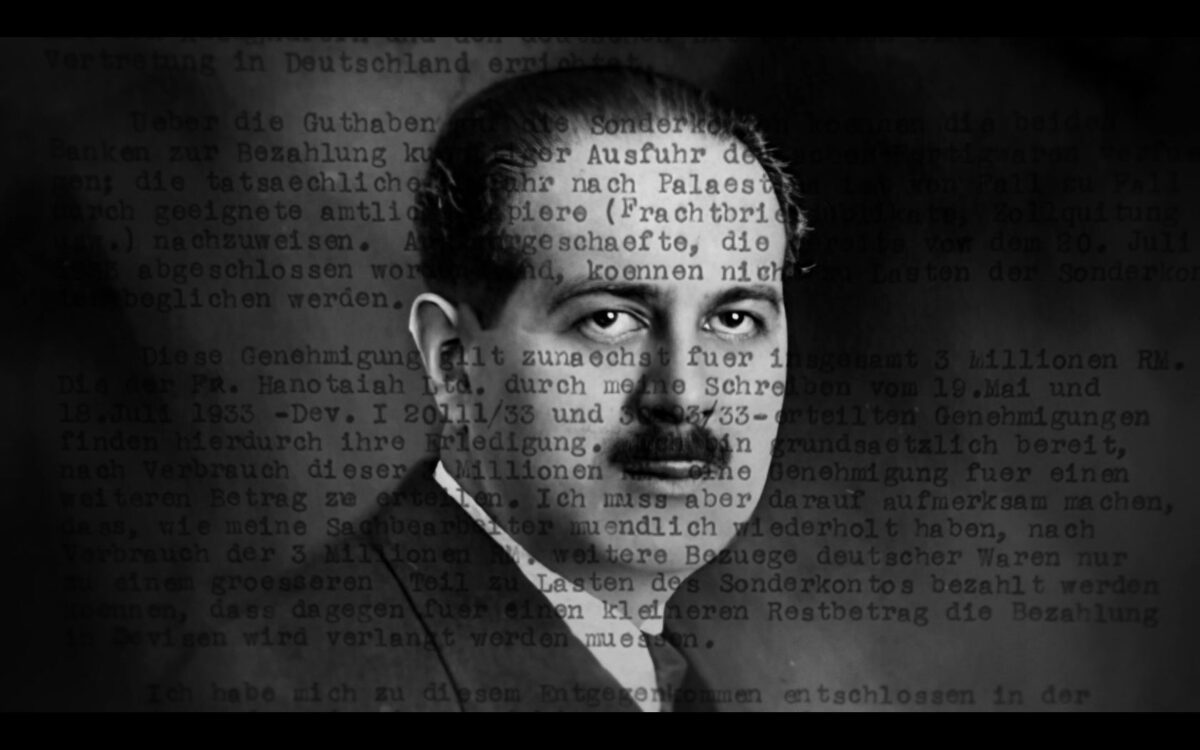

A Deal With the Devil? breaks new ground in that it highlights a usually overlooked element in the narrative. Livny focuses his gaze on Sam Cohen, a citrus exporter in Palestine. A Polish Jew originally from Lodz, he started the ball rolling by signing the first “transfer” agreement in March 1933. His Viennese-born wife, Anita Muller, thought it was a bad idea.

Heinrich Wolff, the German consul in Jerusalem whose wife was Jewish, was of immense help to Cohen, the owner of Hanotea, a company in the seaside town of Netanya. Wolff, an apparent anti-Nazi, contacted Hano Hartenstein, the official in charge of foreign currency in the German Ministry of Economics. Hartenstein convinced the regime that a deal of this sort would be advantageous to Germany.

Such was its success that mainstream Zionists in Palestine not only endorsed it, but enlarged the original agreement. Hitler eventually supported it, but a number of hardline Nazis vehemently opposed it.

In Palestine, right-wing Zionists roundly denounced it as a disgrace. Haim Arlosoroff, an up-and-coming Labor Zionist leader who backed it, was assassinated by Zionist Revisionists.

Practically speaking, the agreement was of the utmost importance to the Zionist movement. Sixty thousand Jews who might otherwise have remained in Germany settled in Palestine. The majority went to Tel Aviv, the first all-Jewish city. Still others founded Nahariya and Kfar Shmaryahu.

More than eight million British pounds worth of German goods, from agricultural equipment to baby carriages, flowed into Palestine. These funds enabled the new immigrants to establish companies ranging from the Assis juice factory and the Tirzah furniture plant to the Dubek cigarette company and the Strauss creamery.

The agreement, though nullified by the outbreak of World War II, was instrumental in the development of a strong Jewish economy in contested Palestine.

Nevertheless, textbooks in Israeli schools have downplayed or ignored the agreement as something of an embarrassment.

As for Cohen, he was quickly forgotten after 1939.

A Deal With the Devil? is an intriguing film inasmuch as it skillfully resurrects an important but little known episode in the annals of Zionism in the Jewish homeland. The screenplay, however, meanders and does not sufficiently focus on the hard, cold facts.