It was, as Steven J. Zipperstein writes in his cinematically vivid book, Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History (Liveright Publishing), “a dreadful moment” burned into the souls of Jews. He is referring to the unbridled anti-Jewish violence that broke out in Kishinev — a provincial Bessarabian city on the edge of the Russian empire — over three days in April of 1903 and resulted in the deaths of 49 Jewish men, women and children.

“Prior to Buchenwald and Auschwitz, no place-name evoked Jewish suffering more starkly than Kishinev,” says Zipperstein, a professor of Jewish culture and history at Stanford University. “No Jewish event of the time would be as extensively documented. None … would leave a comparable imprint.”

Sparked by a blood libel accusation that Jews had satanically killed a Christian child for ritual purposes, the pogrom aroused deep indignation and anger and prompted mass Jewish emigration from Russia. It also inspired the Hebrew poet Hayyim Nahman Bialik to write what is arguably his most influential work, In the City of Killing. And due to the widespread assumption that Russian officials had fomented it, the pogrom pushed some Jews into an embrace of socialism and Zionism.

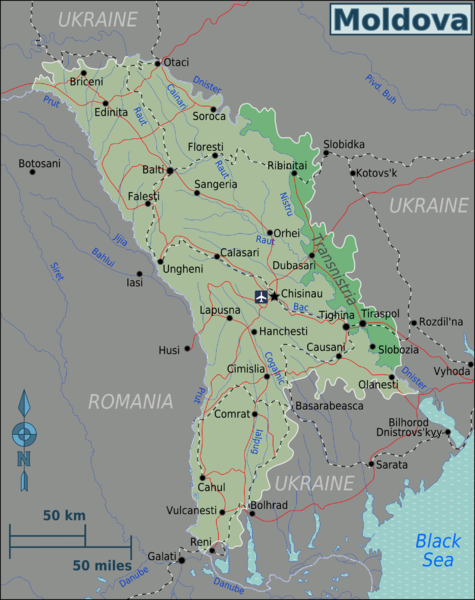

Zipperstein, a specialist in Russia, suggests that antisemitism was deeply ingrained in Bessarabia, which had been a province of the Ottoman empire until 1812. Wrested from Romania by Russia in 1878, it was a poor region inhabited by Moldavans, Russians, Germans, Swiss, Turks, Bulgarians and Serbs where Jews played a visible role as industrialists, shopkeepers, artisans and owners of wine and liquor bars.

Blessed with a balmy climate, Bessarabia was one of Russia’s richest agricultural areas and pasturelands, yielding a cornucopia of maize, wheat, barley, fruit and animal hides. Industry was sparse, but its sawmills, flour mills and factories were lucrative.

Bessarabia, though, was a backwater, with the highest mortality and illiteracy rates, the fewest roads and the least number of doctors in the empire.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Kishinev, with a population of 110,000, was inhabited by about 40,000 Jews. Day-to-day relations between Jews and Christians appeared amicable, and as Zipperstein notes, the ethnic German mayor spoke highly of the role Jews played in the city’s economic life. And as he reminds a reader, Kishinev had hardly been touched by the wave of pogroms that swept through Russia in 1881 and 1882.

Despite these positive notes, Jews were generally regarded as foreigners and were vulnerable to verbal and physical abuse.

As Zipperstein observes, “Their diet, language and clothing, their secrecy despite their obvious volubility, and their many mysteries — perhaps, above all, their purported capacity to resist liquor’s allure — set them apart. They were often thought of as wealthy despite their ubiquitous poverty; they were seen as unnaturally adept at making money while excoriated as unnaturally susceptible to political radicalism. They were loathed for their unwillingness to be absorbed into the fabric of Russian life, though conversion did not necessarily rid them of the taint of Jewish origin.”

According to Zipperstein, the spark that set off the pogrom was the fictitious medieval accusation, repudiated by facts on the ground but widely believed by locals nevertheless, that Jews had utilized the blood of a young Christian to bake their matzohs during the Passover holiday. Such malicious rumors were not uncommon in Russia before the start of Easter.

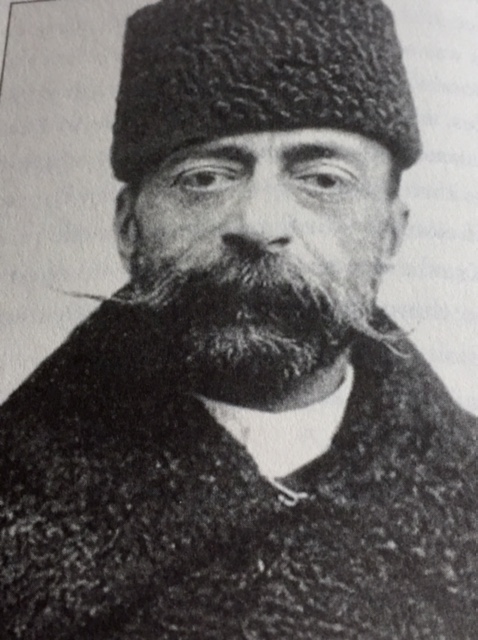

This anti-Jewish animus found its way into the pages of Bessarabets, a minor newspaper owned and edited by Pavel Krushevan, an antisemite who published the first version of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a czarist forgery that would cause Jews untold grief. “The shadow he cast over the pogrom was, by all accounts, considerable,” writes Zipperstein. “His name was cited repeatedly during the massacre, with rioters drinking to his health during the attacks, justifying their violence by citing him as an authority, and calling out his name as they attacked Jews.”

Curiously enough, Krushevan was originally a liberal, a progressive who had mingled with Jews in Vilna and Minsk, two of the most densely populated towns in the Pale of Settlement, where almost all Russian Jews were required to live. His stepsister Anastasia, who would marry a Jew from Kishinev and run off with him to the United States, claims her brother’s animosity toward Jews began only after a Jewish woman jilted him.

In Zipperstein’s view, the instigators of the pogrom were antisemitic activists closely linked to Krushevan, namely the builder Georgi Pronin, who admitted circulating anti-Jewish leaflets in bars and flophouses before the eruption of the pogrom. He was assisted by a magistrate, a semi-literate worker, several doctors and right-wing students.

Zipperstein doubts whether the Russian government was involved in the pogrom, which left hundreds wounded. A few weeks after its occurrence, an incriminatory letter purportedly written by Russian Interior Minister Vyacheslaw Plehve surfaced in which he instructed authorities in Kishinev to stand aside during the pogrom. Plehve certainly disliked and distrusted Jews, regarding them as a disruptive, rapacious and subversive force alien to Russian society. “He hated them because too many were radicals, and he suspected that most of them were insufficiently loyal to the regime.” Nonetheless, Zipperstein contends, claims that he was “unrelentingly anti-Jewish” are “exaggerated and mostly untrue.”

In fact, Plehve’s letter was a forgery concocted by unnamed Russians who agreed with its sentiments. “No evidence exists that Plehve wrote the letter, and there is considerable evidence that he did not.” By Zipperstein’s reckoning, he had a much deeper fear of mass unrest, which is at the core of any pogrom.

Shockingly enough, many of the perpetrators were neighbors of the victims. As Zipperstein says, “This interplay between familiarity and ferocity was replicated in incident after incident. Victims of rape or beating were known to call out the names of their assailants. One raped woman spoke afterward of having held her rapist as a baby in her arms.”

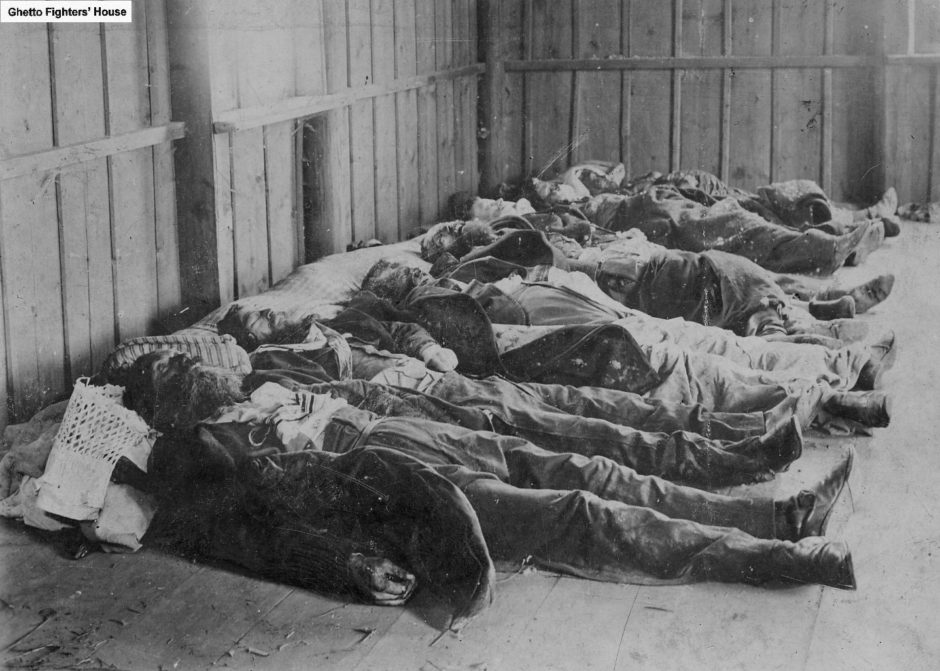

The New York Times reported, “The scenes of horror attending this massacre are beyond description. Babies were literally torn to pieces by the frenzied and bloodthirsty mob. The local police made no attempt to check the reign of terror. At sunset the streets were piled with corpses and wounded.”

An Irish journalist employed by the New York American, Michael Davitt, wrote the most harrowing, mesmerizing and widely read stories about the pogrom, all of which were pro-Jewish. Davitt’s interpreter in Russia for the first day or two was the Jewish leader Meir Dizengoff, who would immigrate to Palestine and become the long-serving mayor of Tel Aviv. Davitt went on to write Within the Pale: The True Story of Anti-Semitic Persecution in Russia, a book culled largely from his graphic newspaper articles.

As Zipperstein points out, Davitt’s views on Jews were complex, “born of sympathy, yet based on unassailable beliefs regarding inbred racial characteristics that presumably led Jews to exploit the weak, ignorant or naive.” In a book published in 1902, The Boer War for Freedom, Davitt singled out South African “Anglicized and German Jews” as exploiters of the Boers, the original white inhabitants of the country.

Surveying the effects of the pogrom, Zipperstein says it convinced innumerable Jews that there was no future for them in Russia. “It would constitute for many the final nail in the coffin for the prospect of Russian-Jewish integration, the ultimate verdict on the necessity for emigration to the United States or Palestine (and) the clearest of all clarion calls for revolution …”

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Kishinev, the capital of independent Moldova, was renamed Chisinau. Known in recent years as a hub of international prostitution, Moldova is bedevilled by corruption and weakened by an ambiguous identity that may encourage Romania or Russia to absorb it one day.

The vast majority of its Jewish residents are gone, having settled in Israel and the United States.

In his concluding remarks, Zipperstein refers to a conversation he had with a local literary scholar, who claimed that Chisinau would have fared far better economically had Jews remained in the city. “Yet she had insisted just a few moments earlier that the real reason for the outbreak of the pogrom was that (Kishinev) was packed with far too many Jews, which justly exasperated locals. Though pressed, she acknowledged no contradiction in what she had just said.”