Claudio Lomnitz’s ancestors were wanderers, as his book suggests.

Lomnitz, a professor of anthropology at Columbia University in New York City, has written a ruminative memoir about his family that will surely strike a chord with Jewish families that were forced to leave their ancestral homes in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Nuestra America: My Family in the Vertigo of Translation (Other Press) takes us on a vivid journey from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires to the Hispanic lands of the new world.

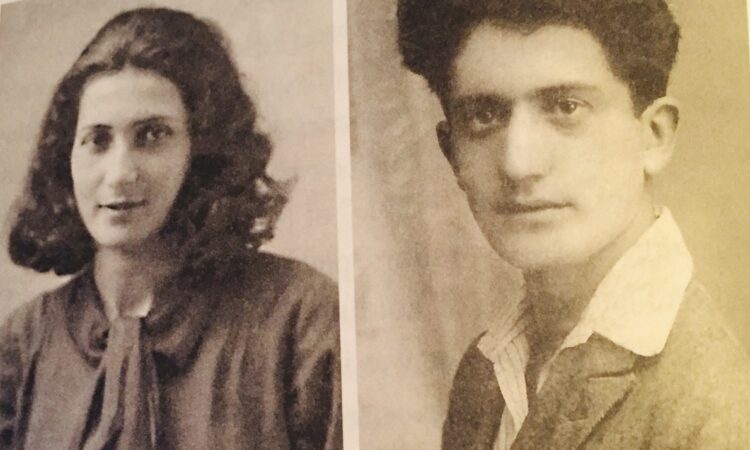

He focuses on his grandfather, Misha Adler, a learned man who immigrated to Peru before setting off to other destinations. In the course of charting his peregrinations, Lomnitz tells us about his parents. Cinna, his father, was born in Berlin. Larissa, his mother, lived in the Bessarabian town of Nova Sulitza before settling in Columbia.

Adler was born in 1904 in Bessarabia, one of the most underdeveloped areas in Europe. Inhabited by Moldovans, Jews, Germans and Greeks, it was rich in agriculture.

Under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, this region was claimed by Romania, the last European country to grant Jews full citizenship rights. From the 1920s onward, however, Romanian Jews suffered from an upsurge of antisemitism. So in towns like Nova Sulitza, sympathy for Zionism swelled, and Adler was one of its acolytes.

He planned to settle in Palestine, but limits on Jewish immigration imposed by the British Mandate authorities compelled him to choose a country even more distant and exotic. He chose Peru, which sought European settlers as “a eugenics-inspired counter-balance to the large number of Chinese immigrants that it had previously received.”

By the late 1920s, Lomnitz writes, there was not a single Jewish family in Nova Sulitza that did not have at least one relative in South America. Most of the newcomers went to Lima, a path Adler followed. He landed there in 1924.

“The Eastern European Jews who arrived in Peru had to operate in a complicated racial hierarchy that was new to them,” says Lomnitz, referring to the deep schism between its Spanish and Indigenous population. “Peru’s desire to foster European over Chinese immigration was such that it was willing to embrace migrants from backward Eastern Europe, and did not even care whether those who came were Jews.”

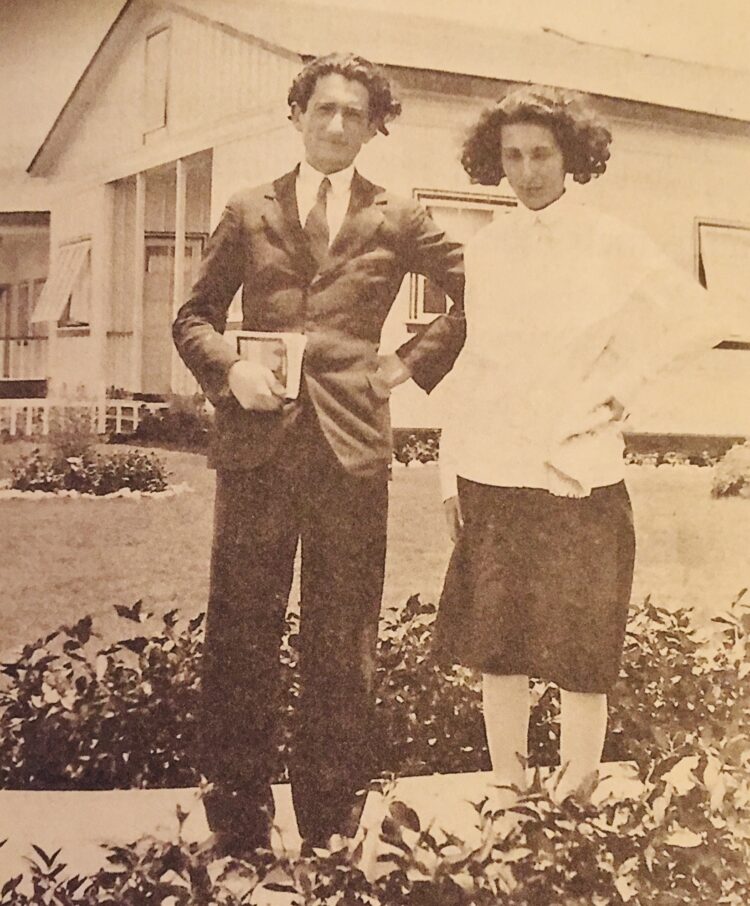

The first Jewish migrants were uniformly men. They became door-to-door salesman who sold clothes on installments. Adler, though not a peddler, found a job managing them. Three years after his arrival, he met, then married, Lisa Noemi Milstein, whose family hailed from the Ukrainian city of Mogilev.

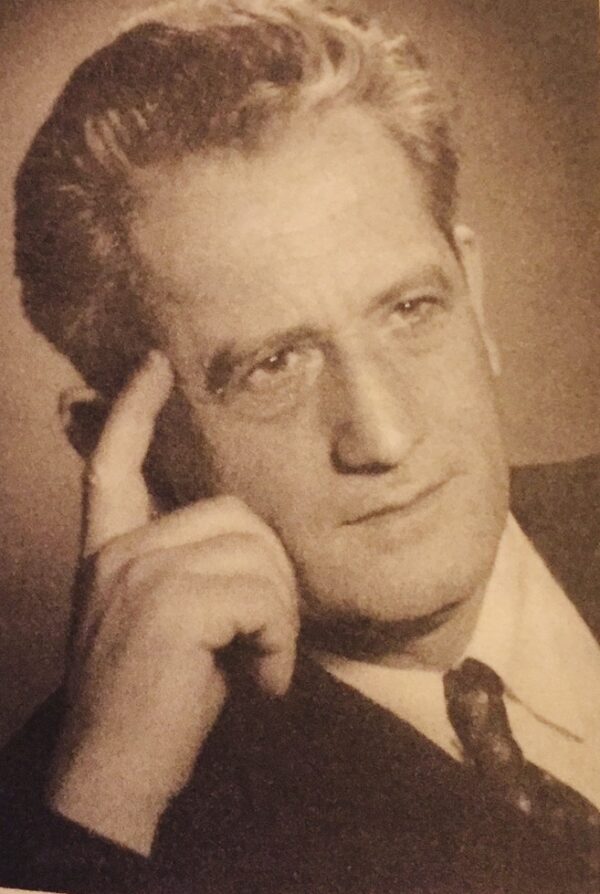

Adler’s real passion was scholarship. In 1930, Adler, a committed socialist, received a PhD degree in philosophy. His dissertation on Karl Marx was the first to be submitted to a university in Peru, says Lomnitz.

He and Noemi knew Jose Carlos Mariategui, one of the founders of Peru’s Socialist Party and a sympathizer of the Zionist movement.

For a brief period, Adler and his wife co-edited a Jewish magazine. Having plotted against Peru’s authoritarian regime, they were arrested. Upon their release, they were deported from the country they had come to love.

They lived in Paris from 1932 to 1934, during which time Adler studied Indo-American ethnology, Jewish ethnology and the scientific critique of racism.

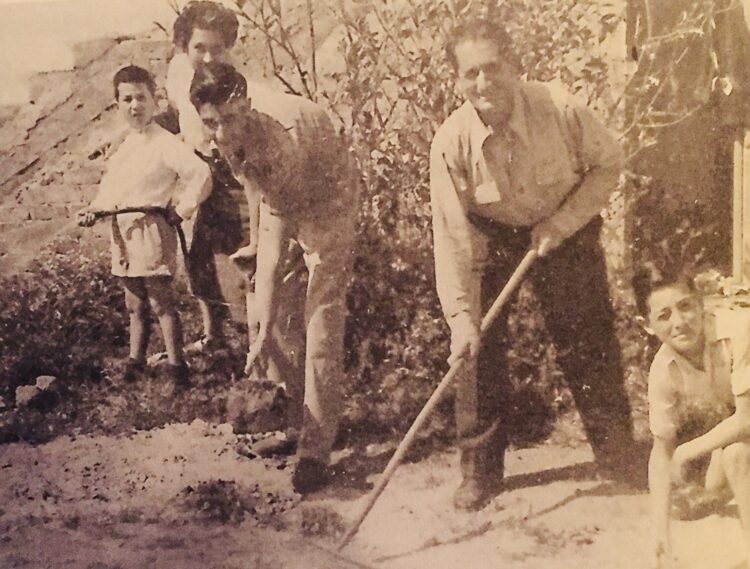

Returning to South America, they went to the Colombian town of Tulua, where their relatives had settled. They soon moved on. Adler successively established Jewish schools in Cali and Bogota. He was also director of the Institute for Colombian-Soviet Friendship and played a role in fostering the Soviet Union’s cultural relations with Colombia.

Unable to obtain Colombian citizenship, the Adlers immigrated to Israel in 1949. “The decision represented for them a new beginning in a land where they would be fully accepted, and where they could and would obtain citizenship,” says Lomnitz.

The Adlers lived on a kibbutz. Adler, who had a gift for languages, earned a living as a Hebrew teacher. Their daughter, Larissa, met her husband, Cinna Lomnitz, there.

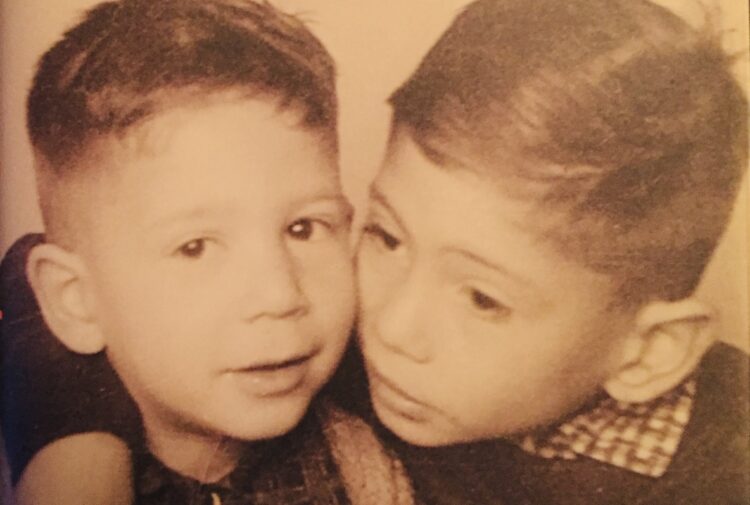

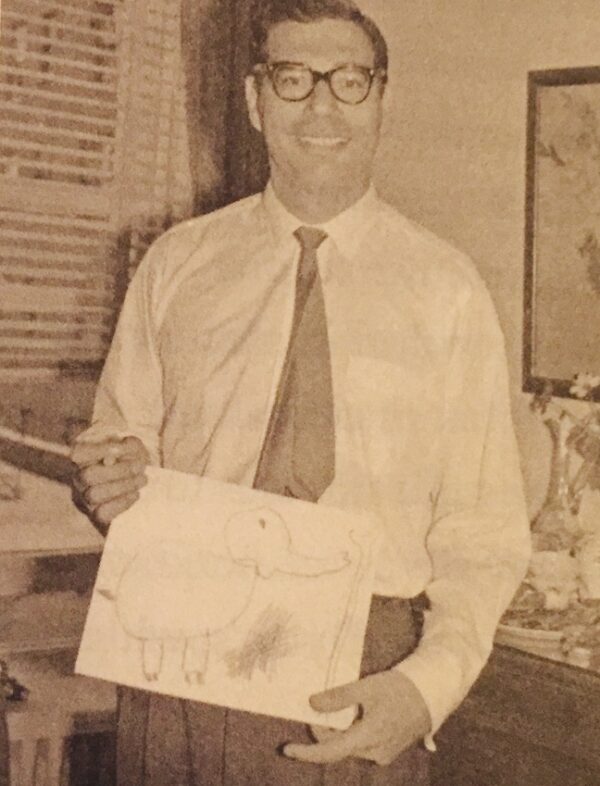

Larissa and Cinna, having grown tired of kibbutz life, were drawn to Beersheba, where Cinna worked as an engineer. They left Israel permanently after he decided to pursue a postgraduate degree in California. Larissa herself would write a doctoral thesis in Latin American urban studies. When Lomnitz was seven years old, his parents moved to Berkeley. In 1968, they all went to Mexico City.

Lomnitz wraps up the loose ends of this sprawling inter-generational story in the final pages of Nuestra America, which speaks to the constant wanderings of Jews in the Diaspora.