As a lawyer and as a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, Ruth Bader Ginsburg has been a force for constructive change in the United States since the 1970s. “She created a legal landscape,” says one of her admirers in RBG, an upbeat and bracing documentary by Julie Cohen and Betsy West due to open in Canada on May 18. “She is the closest thing to a superhero I know,” observes women’s rights crusader Gloria Steinem.

Ginsburg, now 85, helped liberate American women from the shackles of inequality. Case by case, she chipped away at deeply ingrained discriminatory laws, customs and conventions that held women back from their rightful place in society.

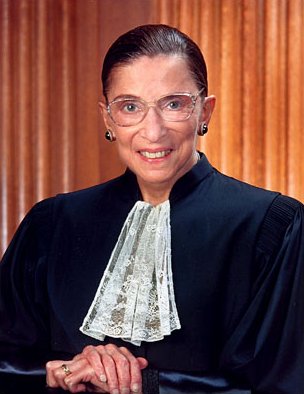

Only the second woman after Sandra Day O’Connor to sit on the Supreme Court, Ginsburg comes across as a shy, reserved, resolute person. The film, composed of home movies, photographs, file footage and interviews, presents her as a quiet and effective reformer whose impact has been profound.

The scion of Russian Jewish immigrants who lacked the means to attend university but who valued higher education, Ginsburg was a bright child who radiated intelligence and magnetism and eschewed small talk. That, at least, is how she is fondly remembered by school friends from Brooklyn, a borough of New York City where she was born and raised.

Ginsburg appears to have had two important personal relationships. She was very close to her mother, who dispensed good advice on people management. She died when Ginsburg was only 17. “I wish I had her longer,” she muses. Ginsburg also lucked out in her selection of a husband. Marty, her spouse for more than 50 years, was her soulmate and cheerleader. He passed away in 2010.

“Marty was the first boy who cared I had a brain,” she recalls. “He never regarded me as a threat.”

They met at Cornell University, fell in love and married.

Ginsburg was the mother of a 14-month-old infant when she arrived to attend Harvard law school in 1956. One of nine women in a class of more than 500 men, she was dogged by the uncomfortable feeling of being watched. Marty, who would be an eminent tax lawyer, supported her career path unreservedly.

At Harvard, Ginsburg was a superb student. But due to a job Marty accepted in New York City, she transferred to Columbia University to finish her law degree. Much to her disappointment, she could not find a position at a law firm. “I became a lawyer when women were not wanted,” she says matter of factly.

As a law professor and lawyer in private practice, she devoted herself to fighting gender discrimination, winning a series of seminal Supreme Court cases that the film examines in some detail.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed Ginsburg to the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C. In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated her for the Supreme Court. Marty played a key role in advocating for her appointment. Confirmed by a margin of 96-3, she was the 107th associate justice to sit on the high court.

As the court turned more conservative, she became one of its liberal dissenters. Despite her ideological leanings, she formed a friendship with one of its most right-wing members, the late Antonin Scalia.

Two bouts with cancer since 1999 have not affected her attendance at court proceedings. But old age is creeping up. In 2015, she was caught nodding off during President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address. Nonetheless, she has no immediate intention of retiring. “I will do this job as long as I can do it full steam,” she told an interviewer recently.

Ginsburg is a careful person, but she slipped in 2016. In an unguarded moment, she described Donald Trump, then a presidential contender, as a “faker.” Quickly recognizing her comment as inappropriate, she apologized.

As RBG suggests, it was one of the very few known mistakes she has ever made in a brilliant career.