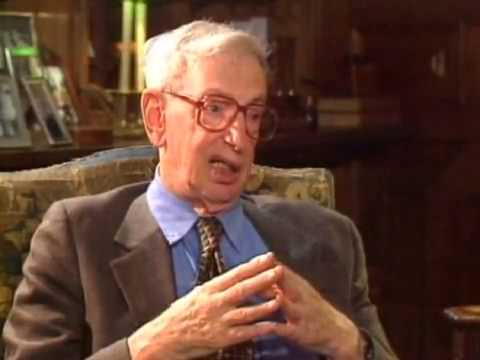

This year being the centenary of his birth, many articles are appearing about one of the 20th century’s most eminent historians, Eric Hobsbawm.

The accolades are coming particularly from the left, as Hobsbawm was a lifelong member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, and chair of its Historians’ Group. As he himself stated, the first decade of its existence from 1946 to 1956 “was the time when we really became historians.”

However, unlike many of his intellectual colleagues and comrades, including Christopher Hill, John Saville, and E.P. Thompson, Hobsbawm did not quit the party even after the crimes committed in the name of Communism by Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union were exposed in 1956.

The Historians’ Group also vociferously protested against Moscow’s suppression of the Hungarian revolt that year, and he himself became a prominent dissident. But he remained a member of the party, to the puzzlement of many of his British friends.

Perhaps Hobsbawm’s own life history provides an answer. First and foremost was the fact that he was a Jew who came of age in the 1930s, when fascism and Nazism were spreading across Europe, spewing vitriolic racial antisemitism in their wake.

In his autobiography, Interesting Times: A Twentieth Century Life, published in 2002, Hobsbawm attributed much of his intellectual development to his unusual life. He was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1917, to Jewish parents — a father from the East End of London, and an Austrian mother.

After World War I ended, they settled in Vienna, but both parents had died by 1931. Before coming to England as a schoolboy in 1933, Hobsbawm lived briefly in Berlin, appalled by the rise of Adolf Hitler.

He took part in the last legal demonstration of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), days before Hitler became chancellor, a response to a display of force by the Nazi SA (Sturmabteilung) Brownshirts.

It seemed to him, as to so many Jews, that the Communists, Hitler’s arch-enemies, were the only ones willing to stop the Nazis. He later explained that he had become a Communist not as a Briton, but as a central European fighting fascism, and so still owed a measure of loyalty to the movement.

“I didn’t want to break with the tradition that was my life and with what I thought when I first got into it,” he told Sarah Lyall in an interview that appeared in the New York Times on August 23, 2003. “I still think it was a great cause, the emancipation of humanity. Maybe we got into it the wrong way, maybe we backed the wrong horse, but you have to be in that race, or else human life isn’t worth living.”

Hobsbawm left behind a prodigious body of work, but is probably best remembered for his three-volume history of what he called the “long nineteenth century”: The Age of Revolution, 1789–1848; The Age of Capital, 1848–187, and The Age of Empire, 1875–1914. He later added to his original trilogy The Age of Extremes, 1914–1991, on the “short” twentieth century. They remain among the standard historical works for the period.

Beginning in 1956, Hobsbawm also moonlighted as a jazz critic for the New Statesman and Nation, writing under a pen name, Francis Newton.

Although I wrote my PhD dissertation on Jewish Communists in Britain, I never met Hobsbawm until 1994, as he wasn’t involved with the ethnically Jewish immigrant working-class movement in London’s East End.

At a conference on “Opening the Books: New Insights into the History of British Communism,” held at the University of Manchester, my paper, “Sidestepping the Contradictions: The Communist Party, Jewish Communists and Zionism 1935-48,” was on the same panel as one of his presentations.

In the book of the conference proceedings published later that year by Pluto Press, Hobsbawm wrote that my paper, demonstrating the “disproportionately great” role of Communism among British Jews, “can throw light on the history of the lesser components of the multi-ethnic nation-state of Great Britain.”

I must say that I was flattered.

When Hobsbawm died in 2012, at the age of 95, an appreciation of his life that appeared in the October 1 edition of the Guardian, the left-liberal London newspaper, contended that Hobsbawm had achieved a unique position in Britain’s intellectual life.

“In his later years,” observed columnist Martin Kettle and University of London sociologist Dorothy Wedderburn, “he became arguably Britain’s most respected historian of any kind, recognized if not endorsed on the right as well as the left, and one of a tiny handful of historians of any era to enjoy genuine national and world renown.”

Most remarkably, they noted, he “achieved this wider recognition without in any major way revolting against either Marxism or Marx.” A year before his death Hobsbawm published How to Change the World: Tales of Marx and Marxism, a defense of Karl Marx’s continuing relevance in the aftermath of the 2008 recession.

And, we must remember, by then the USSR had not only been ideologically discredited but had in fact dissolved, along with its former east European satellite states! Hobsbawm’s own life span had lasted longer than that of the Soviet Union.

But are the ideals he espoused also really dead? Not according to Joseph Fronczak, a Princeton University historian, in an on-line June 9 article, “Hobsbawm’s Long Century,” published in the Jacobin, the left-wing quarterly published in New York.

“Hobsbawm’s vision of humanity-encompassing Enlightenment ideals expressed politically in the form of socialism, seemingly dead at his short century’s end in 1991, now in 2017 suddenly appears once more in surprisingly sturdy shape,” he asserts, “fortified for what looks to be another long century.”

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.