At a moment when jihadism is on the rise and Israel’s relationship with the Palestinians has reached a nadir, Princeton University Press’ encyclopedic volume, A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations, is a welcome addition to our fount of knowledge.

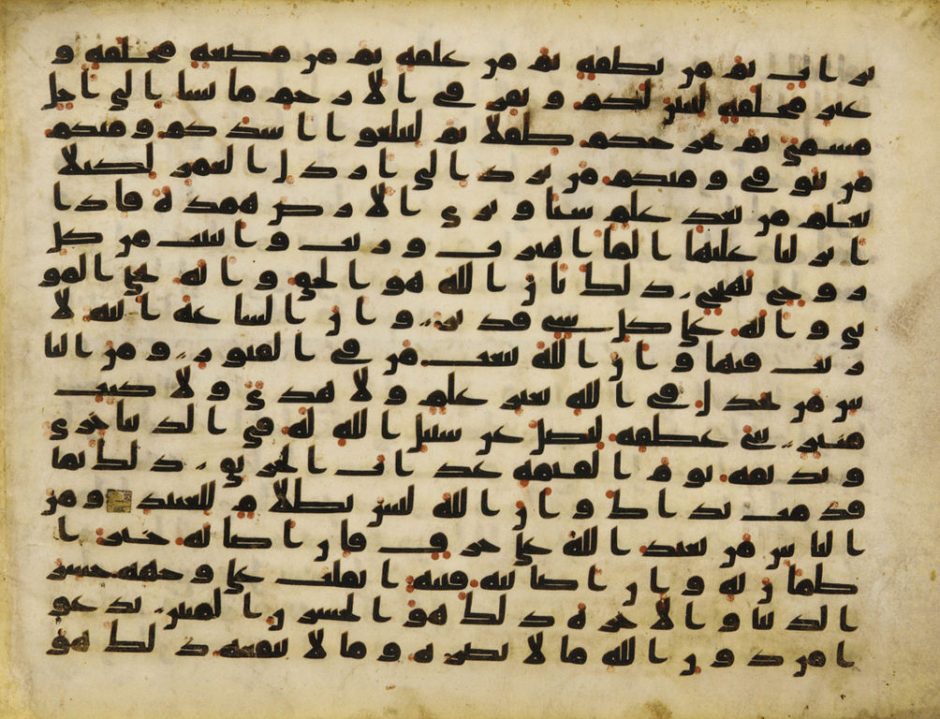

More than 1,100 pages in length, and lavishly illustrated, this authoritative tome should be required reading for those who are even mildly interested in this weighty topic.

Edited by Abdelwahab Meddeb and Benjamin Stora, and containing some 150 essays by experts in history, politics, religion, philosophy and anthropology, it’s divided into four parts: the medieval period, the early modern era through the 19th century, the 20th century and the connections between Jews and Muslims.

Having dipped into it, I found it to be an erudite and even-handed guide to a complex subject.

The first essay, by Mark R. Cohen, separates myth from reality in Jewish-Muslim relations during the Middle Ages. Pointing out that certain 19th century historians painted an idealized picture of it, he contends that this “interfaith utopia” was something of a myth. “It ignored, or left unmentioned, the legal inferiority of the Jews and periodic outbursts of violence,” he says.

The European historians who created this myth, some of whom were Jewish, were disappointed by the failure of the Enlightenment to wipe out antisemitism and produce real equality. With the rise of political Zionism, Muslims appropriated the myth as a weapon to be used against the Zionist movement and the state of Israel.

Cohen goes on to discuss the dhimma system, which regulated the lives of Jews and Christians under Muslim rule. Jews had substantial confidence in it, he notes. “If they kept a low profile and paid their annual poll tax, they could expect to be protected and to be free from economic discrimination (and) not to be forcefully converted to Islam, massacred or expelled.”

Cohen, in another essay, points out that Mohammed the Prophet initially adopted a conciliatory attitude toward Jews and adapted several Jewish practices in the hope of converting them to Islam. Most Jews rejected his teachings, resulting in hostile references to Jews in the Koran and other early Islamic sources, which, he claims, are “packed with anti-Jewish … venom.”

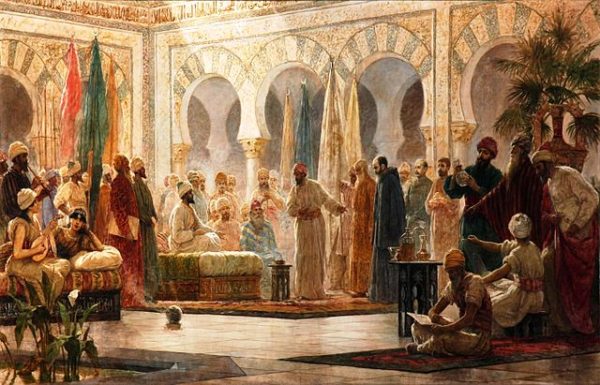

In The Jews of al-Andalus, Mercedes Garcia-Arenal says that Jews in Muslim-dominated regions of Spain experienced great material prosperity and, in some instances, played a key role as viziers. One such figure, Hasdai ibn Shaprut, was a patron of Jewish letters who set in motion the “Hebrew Golden Age,” a two-century era of extraordinary literary achievement.

Mohammed Hatimi, in The Conversion of Jews to Islam, argues that Jewish elites had the most to gain from abandoning Judaism. “Conversions occurred out of conviction or opportunism — or out of love,” he says. Some Jewish converts, like the Moroccan Yahya al-Maghribi, displayed a marked hostility to Jews.

Gilles Veinstein writes about the immigration of Jews into the Ottoman Empire before the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. Sephardic Jews began arriving in Ottoman lands as far back as 1391, following the Almohad persecutions. Mehmed II, the Ottoman sultan, recognized “the usefulness of Jewish contributions to his fledgling state.”

In his second essay, Veinstein argues that the 16th century represented “a kind of golden age of Ottoman Jews, an apogee of their economic and financial position, and even, to a certain extent, of their political influence.”

Lale Uluc, in Images of Jews in Ottoman Court Documents, claims that more Jews lived in Ottoman lands than elsewhere for much of the 16th and 17th centuries. How true is that? What about Jews in the Russian Empire?

In The Jews of Palestine, Yaron Ben Naeh writes about the Jewish community during the Mamluk era. The community was composed of Arabic-speaking natives, Jews from North Africa and Spain and a handful of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim. They were concentrated in five cities — Jerusalem, Safed, Gaza, Nablus and Hebron — and in a few villages in the Galilee. “The Jews and their Muslims neighbors lived in close proximity, and no particular ostracism was observed. They rubbed shoulders in the urban centers where they worked side by side … Men frequented the same cafes and hammams.”

European Jews who arrived in Palestine from the 18th century onward created problems for the Ottoman authorities because they sought to place themselves under the protection of powers like the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Britain and Russia, writes Nazmi Al-Jubeh in The Jews of Jerusalem and Hebron During the Ottoman Era. Jewish relations with Palestinian Christians were less than ideal, he notes. “On the other hand, it is not rare to see Jews residing in the same houses with Muslims and sharing their daily life, sometimes even certain jobs.”

Jewish merchants in the Moroccan town of Essaouira were intermediaries between Morocco and Europe, writes Daniel J. Schroeter in a brief essay. “The interdependency between Muslims and Jews helped maintain a system of relative trustworthiness: Muslims depended on Jewish brokers to market their merchandise, while Jews depended on Muslim transporters to convey their goods over long distances.”

Vera Basch Moreen, in The Jews in Iran, says that minorities living under the sway of the Safavid dynasty (1501-1736) were considered impure. Jews, in particular, occupied the lowest strata of society and were increasingly marginalized and oppressed. As a result of a blood libel accusation, the Jewish community of Tabriz was destroyed in 1791. And in 1839, the Jews of Mashad were forced to convert to Islam.

In Iranian Paradoxes, Katajun Amirpur focuses on the period in Iran following the 1979 Islamic revolution, which deposed the monarchy of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Under the shah, the Jewish community flourished and Iran maintained cordial relations with Israel. But under the new Iranian regime, Jews briefly faced uncertainties and ties with Israel were severed. Many Jews emigrated, but eventually, Iran made a distinction between Israel and Iranian Jews, while Iran’s spiritual leader, Ayatollah Kohmenei, renounced his antisemitic views for a more balanced and tolerant approach.

Michel Abitbol, in The Diverse Reactions to Nazism by Leaders in Muslim Countries, writes about Haj Amin al-Husseini’s flirtation with Nazi Germany, its plans to extend its influence in the Middle East and the 1941 pogrom in Baghdad, which claimed the lives of upwards of 180 Jews.

The emigration of Jews from the Arab world after Israel’s proclamation of statehood in 1948 is the subject of Michael M. Laskier’s essay. He cites the deteriorating conditions of Jewish communities in an array of countries from Morocco and Syria to Algeria and Egypt.

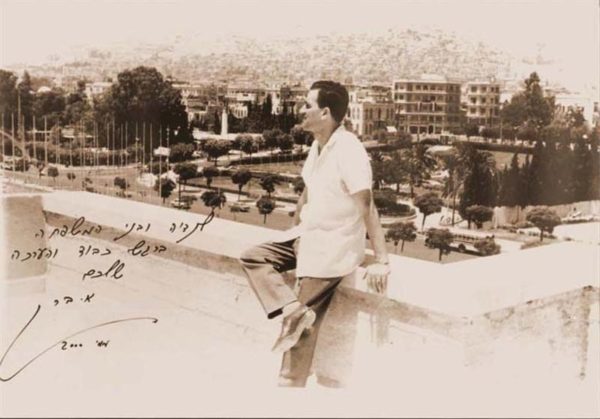

As far as Syria is concerned, he says that hostility toward Jews increased after Israeli spy Eli Cohen was caught and hanged. He claims that the situation for Jews improved after Hafez al-Assad seized power in 1970, even though their freedom of movement and right to emigrate remained limited.

Lebanon was a different story, says Kirsten E. Schulze in The Case of Lebanon: Contemporary Issues of Adversity. Anti-Jewish riots broke out in Tripoli in 1945 and in Beirut after the 1947 Palestine partition plan and the emergence of Israel. The Lebanese government, however, disapproved of such violence and sent in police or the army to protect Jews. In the wake of the first Arab-Israeli war, she adds, Muslim-Jewish relations returned to their “friendly character” and Lebanon absorbed Jewish emigrants from Syria and Iraq. Consequently, Lebanon became the only Arab state in which the number of Jews grew exponentially, from 9,000 in 1950 to 14,000 in 1958. The Six Day War, though, was a turning point as innumerable Jews left Lebanon.

Nora Seni’s essay, Survival of the Jewish Community in Turkey, charts its decline from the 1934 pogroms in Edirne, Tekirdag and Kirklareli, the 1942 wealth tax, the establishment of Israel and the 1955 riots in Istanbul targeting Greeks, Jews and Armenians. Yet Turkey values the Jewish community, however diminished, as proof of its commitment to tolerance.

Arab perceptions of the Holocaust are discussed by Esther Webman in her essay. In general, Arab reaction has ranged from justification to denial, while Arab intellectuals have refused to acknowledge the Holocaust out of concern that it would diminish the plight of the Palestinians. According to Webman, Arab scholars have written few original studies on the Holocaust.

Mark R. Cohen’s essay, Muslim Antisemitism: Old or New?, posits the position that “Muslims first came into contact with European-style antisemitism in the Ottoman period, when the Islamic world absorbed new Christian populations.” He says it took off in the 19th century, when European missionaries spread anti-Jewish tropes. “Antisemitism in the Arab Middle East grew in intensity after the rise of political Zionism” and was fanned by Nazi propagandists in the 1930s and 1940s.