Thousands of Italian women joined the anti-fascist resistance between September 1943, when Italy surrendered and joined the Allies, and April 1945, when Italy was finally liberated from the fascist regime and the German occupation.

During this tumultuous 19-month period, Italian partisans fought not only the Germans, but clashed with Benito Mussolini’s Nazi-supported fascist government in a nation-wide civil war.

“This tragedy, outside Italy, is seldom remembered,” writes Caroline Moorehead in her substantive book, A House in the Mountains: The Women Who Liberated Italy From Fascism, published by Random House. “It is a story that deserves to be told.”

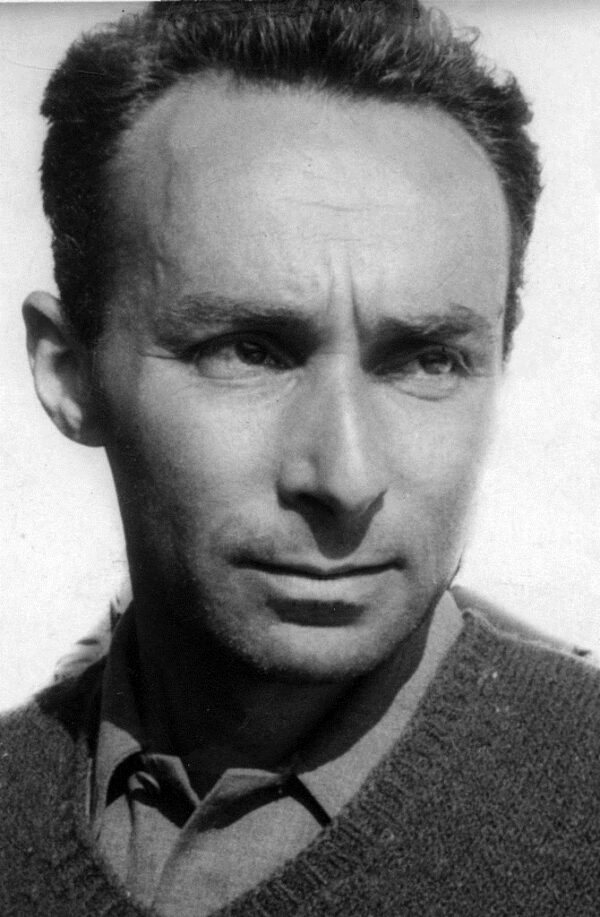

Moorehead’s narrative unfolds, in part, through the experiences of several liberal-minded women from the northwestern industrial city of Turin, the headquarters of the Fiat automobile company and the hometown of the author and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi.

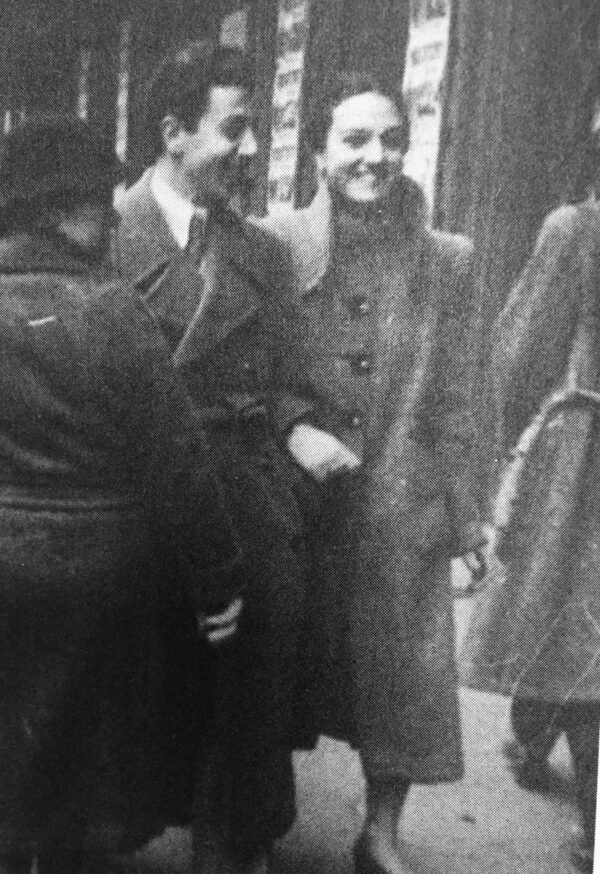

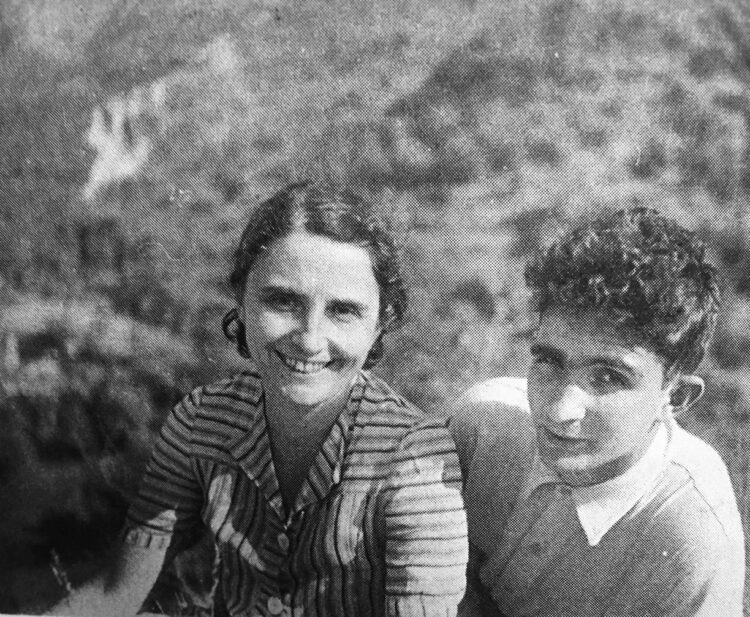

The women, bound by the bond of friendship, were Ada Gobetti, a teacher and translator, Bianca Guidetti Sera, the editor of clandestine women’s newspapers banned by the fascists; Frida Malan, a university student and the only Protestant among this Catholic circle, and Silvia Pons, a physician.

“What made these women extraordinary was that fascist Italy had turned them into shadows: they had no rights, no voice, no equality, no say in either their own lives or in the running of the country,” says Moorehead. “That they found the courage, the imagination and the selflessness to fight — and often to suffer arrest, torture, rape and execution — is what made them truly exceptional.”

Like the vast majority of Italian women, their lives were circumscribed by Mussolini’s misogynist views. “Few had questioned his diktat that the function of a women was to marry and produce children, preferably boys, for the patria.”

This servitude vanished as a great many women decided that patria had a totally new meaning. They would no longer pledge allegiance to a fascist dictator, but to a different and egalitarian kind of Italy where they could flourish and prosper.

For Bianca and Frida, there was another reason to take up arms against the fascists: the passage of antisemitic laws in 1938 that had demonized and marginalized their Jewish friends.

The events that compelled them to risk their lives for a noble idea took flight in the summer of 1940, when neutral Italy — an ally of Nazi Germany — joined the Axis powers in World War II. The war went so badly for Italy that, on July 24, 1943, the Fascist Grand Council convened in Rome to settle the question of Mussolini’s leadership.

Nineteen of its 27 members accused him of having pursued a “disastrous foreign policy” and of having “imposed a dictatorship” on Italy. They then voted to unseat him as leader after more than decades at the helm.

On the heels of this momentous decision, the king asked Marshal Pietro Badoglio, a war hero, to form a non-fascist government. “It was a coup, a bloodless revolution, without a shot fired,” says Moorehead.

Adolf Hitler came to Mussolini’s assistance as Germany invaded and occupied Italy to restore fascist rule. Meanwhile, a German commando squad, led by Otto Skorzeny, rescued him from house arrest in a hotel in the Abruzzi mountains and installed him as the head of the new Salo republic in the town of Gargnano, near Lake Gardo.

“In exchange for the restoration of fascist rule, Mussolini was to cede territory to a newly enlarged Austria, supply Italian labor and machinery for the German war effort and sack a few of his more troublesome followers,” says Moorehead.

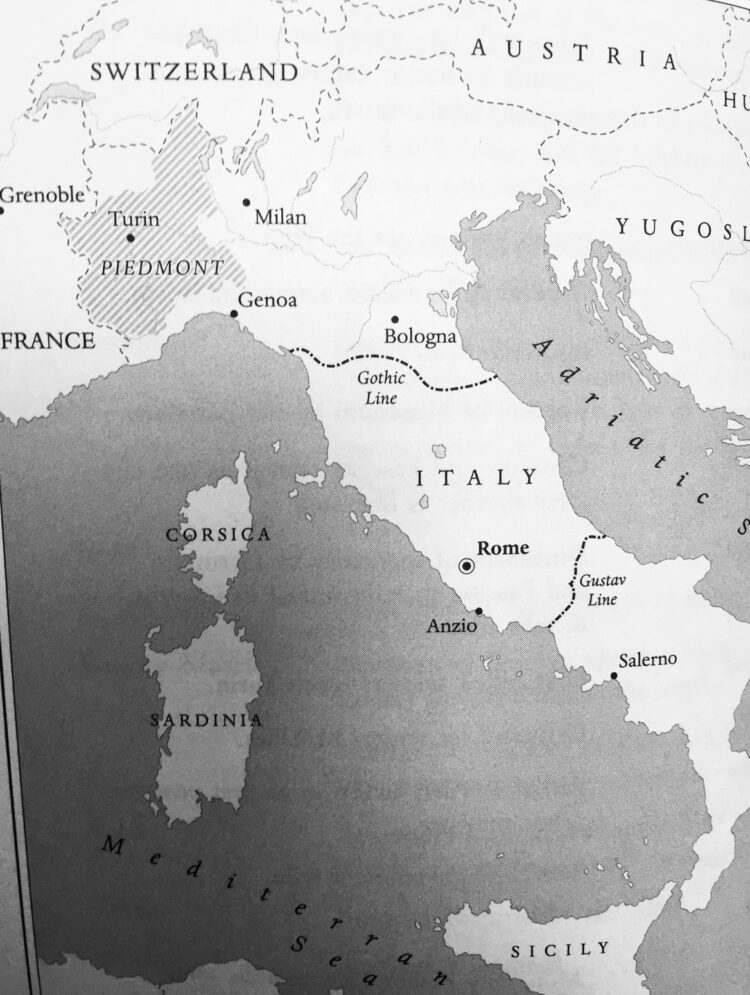

Italy was now cut in two. The north and the center, demarcated by the Gothic Line, were occupied by Germany and Italian fascists, and the south was in the hands of the Allies. Italy was governed by three separate governments: Salo in the northeast, Badoglio in Brindisi, and a six-party underground coalition in Rome.

Amid the confusion and chaos, the Germans, aided and abetted by local fascists, began to round up Jews and deport them to Italian labor and Nazi extermination camps. By then, the 45,000 Jews of Italy had been subjected to a litany of antisemitic laws that rendered them second-class citizens and jeopardized their lives.

By Moorehead’s estimate, 6,806 Jews were deported on 48 transports to Poland, of whom 836 survived, including Primo Levi.

Italian partisans, though short of weapons, fought the Germans and the fascists tooth-and-nail. Germany dealt harshly with them. One-fifth of the 200,000 partisans were killed. Throughout the course of her book, Moorehead documents the activities in which Ada, Bianca, Frida and Silvia participated.

Jewish partisans contributed a disproportionately high number of fighters to the resistance movement. Well over 2,000 joined and close to half were arrested, executed or deported.

By the close of the war, Italy’s infrastructure was largely destroyed and its health system was in ruins. Following the entry of Allied troops into Turin on April 30, 1945, partisans exacted vigilante justice on local fascists. “Nowhere was the spirit of revenge more visible nor the number of reprisals higher than in Turin, long regarded as the epicentre of fascist and German sadism but also of the northern resistance,” writes Moorehead.

All over this elegant city, collaborators and informers were ruthlessly hunted down and quickly executed. Italian women who had slept with Germans were treated with the utmost disdain and even violence. As for Mussolini, he was caught trying to escape, shot and strung up along with his mistress and a few of his associates.

Unlike Germany, Italy did not haul its leading war criminals into a court to stand trial. “What mattered most was not justice, but reconstruction,” writes Moorehead indignantly.

Several thousand fascists were imprisoned, but they were released soon after the war. Fascists who had turned Jews over to the Germans and had sent partisans to their deaths were eventually set free.

Nor was Italy’s fascist-tainted judiciary purged.

In 1946, Italy staged eight major exhibitions about the resistance, but as Moorehead observes, “women flitted across them like shadows.”

She adds bitterly, “It would take twenty years and the arrival of the feminist movement before Italian women partisans — along with Jews and the clergy who had fought and died with them — received their due.”