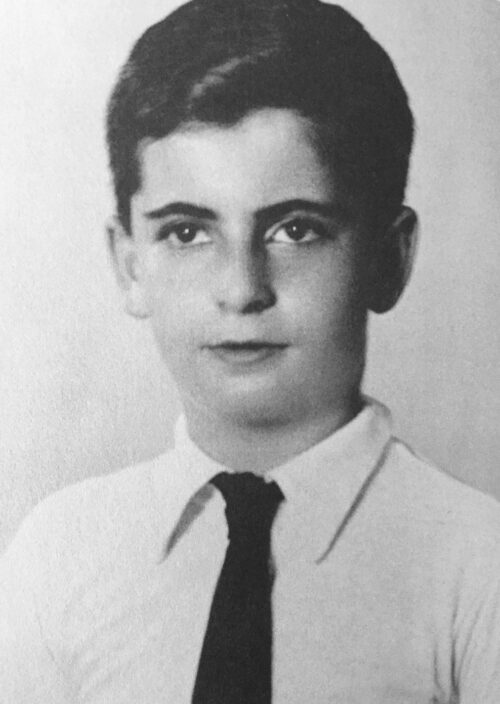

Otto Ullmann, a 13-year-old Jewish boy in Nazi-occupied Austria, bid his parents farewell in Vienna in 1939, just months before the outbreak of World War II. He was bound for Sweden, where he would live the rest of his life.

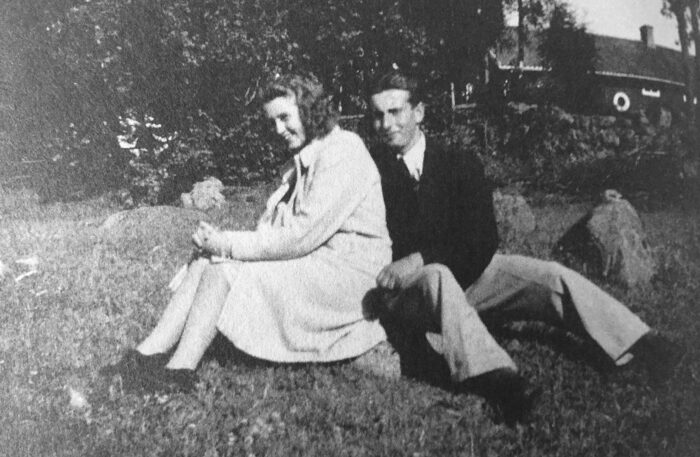

Ullmann spent a year in a Swedish orphanage and then obtained work as a farm laborer. He and the landowner’s son, Ingvar Kamprad, bonded.

It was a very odd friendship. Influenced by his father’s fascist beliefs, Kamprad joined Sweden’s hard-core Nazi party. During World War II, when Sweden was neutral, Kamprad started IKEA, a company that would become the world’s largest furniture retailer. For a while, Ullmann was Kamprad’s right-hand man at IKEA. Kamprad, though antisemitic, regarded Ullmann as his best friend.

Their highly unusual relationship is one of the elements of Elisabeth Asbrink’s unusually different book, And in the Vienna Woods the Trees Remain: The Heartbreaking True Story of a Family Torn Apart by War, published by Other Press.

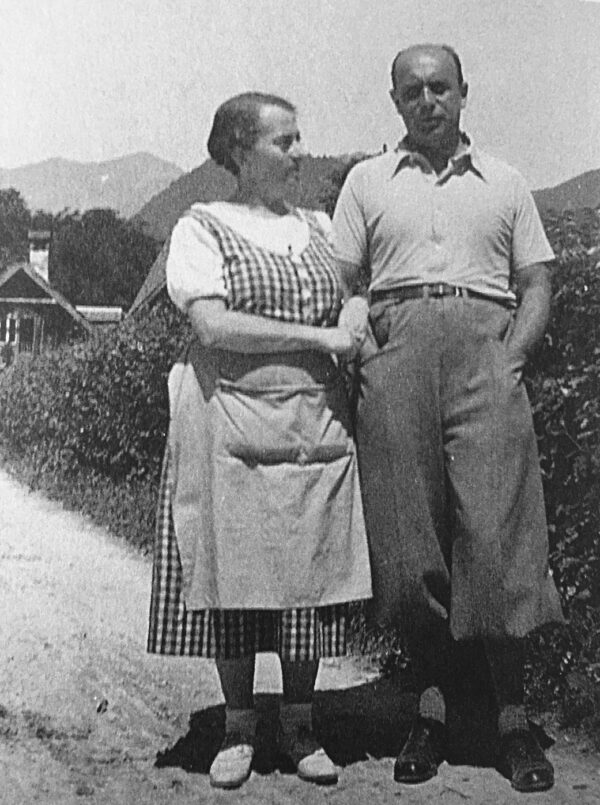

Born on July 20, 1925, Ullmann was the only child of Josef and Elise. Reading the handwriting on the wall, they arranged for their son to be sent abroad. He was very fortunate to be admitted to Sweden. Jewish refugees seeking asylum there were granted entry permits only in exceptional circumstances.

As Asbrink, a Swedish journalist, points out, Swedes were not accustomed to new immigrants and antisemitism was fairly widespread in the country.

The centrist prime minister, Per Albin, believed it was necessary “to preserve a certain restrictiveness” in Sweden’s immigration policy. The leader of the left-of-center Social Democratic Party claimed that while many Swedes were not antisemitic, they feared that an influx of even a few thousand Jews would stir up antisemitism. Right-wing politicians made no attempt to conceal their opposition to the entry of Jewish refugees.

Ullmann’s parents in Vienna circumvented this obstacle by contacting the Swedish Israel Mission, which sought to convert Jews to Christianity. On the basis of its recommendation, the Swedish government granted 45 Jewish children in German-occupied Austria the right to reside in Sweden.

Several years later, Sweden liberalized its immigration policy by admitting several thousand Danish Jews, who reached Denmark’s shores by boat. When the war ended, a further 7,000 displaced European Jews were permitted to settle in Sweden.

After living in Sweden for more than a year, Ullmann turned up at Feodor Kamprad’s estate as a farmhand. Kamprad was a fierce anti-Communist as well as an antisemite. His son, Ingvar, shared his views and was a follower of Per Engdahl, a Swedish fascist who maintained that Jews are a “foreign element” in Western societies and must be removed from leading positions. His solution: deport Jews to a “specifically designated place” and stop all Jewish immigration.

Ingvar Kamprad was 18 when he met Ullmann for the first time. Despite his extreme xenophobic outlook, he took a liking to him. “He didn’t see a connection between his ideology and the Jewish refugee toiling at his side,” writes Asbrink.

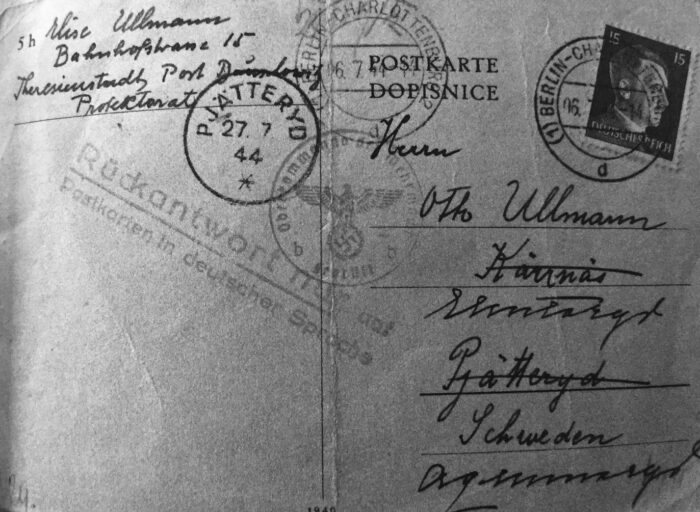

During the war years, Ullmann received a steady stream of letters from his parents, who were eventually shipped to the Nazi Theresienstadt camp in Czechoslovakia. Upbeat in tone, the letters stopped arriving in the summer of 1944. Josef Ullmann, 51, and Elise Ullmann, 53, were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on September 28 and October 3 respectively. Neither of them survived.

Ingvar Kamprad founded IKEA in 1943, and Ullmann was his chief lieutenant. Ullmann performed his job to his boss’ satisfaction, but resigned after a year.

Ullmann left the Kamprad farm after the war and found a variety of jobs in Stockholm. His application for Swedish citizenship was denied. He finally became a citizen in 1955 on his third attempt.

In November 1948, as the War of Independence raged, he volunteered to serve in the Israeli army. Oddly enough, Asbrink says he “travelled to Palestine to fight for Israel.” He stayed for nine months. “No words or documents remain from that time in the desert and his assignment as a sniper,” she writes.

Ullmann got married and eventually had three children. For a while, he worked as a journalist. Later, he ran an advertising business and opened a restaurant. He died in 2005.

Asbrink interviewed Ingvar Kamprad in preparation for writing this book. But after she unearthed evidence in the Swedish Secret Police Archive that he had been a member of the Swedish Socialist Unity Party, Sweden’s homegrown Nazi Party, he severed all contact with Asbrink. Kamprad died in 2018.

Asbrink’s book, translated into English from Swedish by Saskia Vogel, sustains a reader’s interest and proves yet again that necessity is the mother of resilience and survival.