Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas met Ehud Olmert, the former Israeli prime minister, in New York City a few days ago, and predictably enough, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu vociferously condemned their meeting as “shameful” and “disgraceful.”

For Netanyahu, Olmert and Abbas were convenient targets.

Twelve years ago, they came tantalizingly close to reaching a peace agreement on the basis of an equitable two-state solution. Under the plan, borders would be more or less based on the pre-1967 ceasefire lines, land swaps would take place, a division of Jerusalem would occur, and the Palestinian refugee problem would be symbolically resolved.

If it had been implemented, it might have normalized Israel’s contentious relationship with the Palestinians.

Regrettably, Abbas never replied to Olmert’s far-reaching proposal, possibly because Olmert was a lame duck leader on the cusp of being indicted on charges of corruption. Shortly after presenting it, Olmert resigned. Following his conviction, he served 16 months in jail, the first Israeli prime minister to be imprisoned.

On February 11, Olmert and Abbas met in private and then appeared at a joint press conference, just hours after Abbas denounced the United States’ “vision” of peace,” which was unveiled with fanfare in Washington, D.C. on January 28.

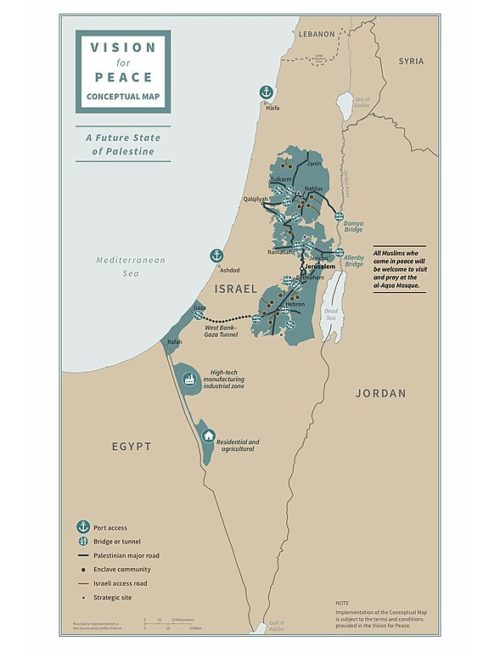

President Donald Trump’s one-sided peace plan, which favors Israel, was roundly rejected by the Arab League and the European Union. Predicated on Palestinian acceptance of all its conditions, it offers the Palestinians a demilitarized and truncated state broken up into enclaves in about 70 percent of the West Bank. Abu Dis, a suburb of Jerusalem, would be its capital. Israel would retain western and eastern Jerusalem and the Jordan Valley. The settlements and outposts would be annexed by Israel. The Israeli army would be in charge of security in the West Bank and all border crossings. There would be no “right of return” for Palestinian refugees. The Palestinians would recognize Israel as a Jewish state.

The Palestinians have been given four years to accept the plan, which Abbas has denounced as the “slap of the century.”

Certainly, it’s a pale imitation of Olmert’s generous offer, and Abbas did not mince words in rejecting it in a speech before the United Nations Security Council. Charging that it enshrines Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, and will bring neither peace nor stability to the Middle East, Abbas said he was ready to enter into direct negotiations with Israel under the auspices of the Quartet, composed of the United States, Russia, the European Union and the United Nations. Abbas also said he would not resort to violence and terrorism to achieve Palestinian objectives. As he put it, “We will fight by way of popular, peaceful resistance.”

During the press conference, Abbas called for a resumption of talks he had held with Olmert. Over a three year period, they met 36 times, usually in Jerusalem. By contrast, Netanyahu has met Abbas only a few times, and he and his associates have repeatedly dismissed Abbas as a suitable partner for peace. In the meantime, Netanyahu’s government has expanded Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

By no coincidence, Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, Danny Danon, claimed on February 11 that peace will remain elusive as long as Abbas is president of the Palestinian Authority. “Only when he steps down can Israel and the Palestinians move forward,” he claimed. “A leader who chooses rejectionism, incitement and glorification of terror can never be a real partner for peace.”

Lambasting the Israeli government’s glib campaign of demonization against Abbas, Olmert described him more accurately as a “worthy partner,” “a man of peace,” “the only partner we can deal with,” and “the only partner in the Palestinian community who represents the Palestinian people.”

Abbas has his faults, to be sure, but in his speeches he has consistently rejected terrorism and supported a two-state solution on the basis of the 2002 and 2007 revised Arab League peace proposal. It calls for a full Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank, the creation of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza, with East Jerusalem as its capital, and a mutually accepted resolution of the Palestinian refugee issue.

Historically, Abbas is one of the most moderate leaders the Palestinians have ever produced. He is far more forthcoming than his predecessor, Yasser Arafat.

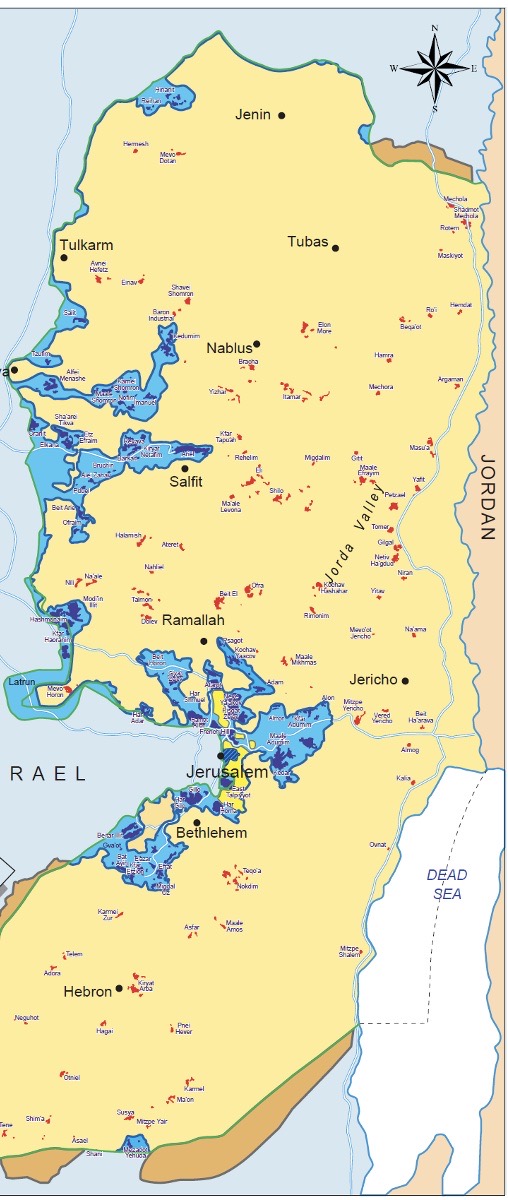

Olmert recognized these qualities in Abbas during the course of their protracted negotiations. In exchange for a peace treaty with the Palestinians, he offered Abbas an unprecedented proposal — a near total Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank, a demilitarized Palestinian state in almost all of the West Bank, a capital in the eastern sector of Jerusalem, and administration of Jerusalem’s Holy Basin by Israel, Palestine, the United States, Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

According to Olmert, Israel would be responsible for border crossings, and in mutual land swaps, Israel would retain major settlement blocs: Ariel, Jerusalem-Maaleh Adumim and Gush Etzion, amounting to 6.3 percent of the West Bank. By way of compensation, Israel would give the Palestinians 5.8 percent of Israeli territory around Afula, Tirat Zvi, Lachish, and areas close to Har Adar and the Gaza Strip. Israel would relinquish a bit of more land to the Palestinians so that a tunnel could be built between the West Bank and Gaza.

As for Palestinian refuges, Israel would accept a symbolic number of 5,000 over five years.

Olmert presented these proposals to Abbas at his residence in Jerusalem on September 16, 2008, and both sides agreed to meet the following day to finalize Israel’s border with a Palestinian state. Abbas called to postpone the meeting, saying he had a previous engagement in Jordan and would be available the following week.

In fact, Abbas never responded to Olmert’s offer. “I’ve been waiting ever since,” Olmert told The Tower.org in an interview last week.

As Olmert said the other day, Abbas never explicitly rejected his offer. But why did he not respond? Was it because Olmert was already in deep trouble with the law? Or was it because the Palestinians were not prepared to accept Olmert’s offer? A comprehensive answer has yet to emerge.

But at his press conference with Abbas a few days ago, Olmert made one thing crystal clear: he did not go to the United States to criticize the Trump peace plan, but to endorse two important principles: peace will be possible only on the basis of a two-state solution, and peace can only be achieved by direct talks between Israel and the Palestinians. He acknowledged that Trump’s peace plan, at least in theory, recognizes the necessity of a two-state solution.

Olmert’s fair-minded and balanced comments were too much for Netanyahu, who faces another election on March 2 and has been indicted on three charges of corruption. Branding Olmert’s meeting with Abbas as a “low point in Israeli history,” he suggested that the Trump plan is the only viable way forward.

This was nothing less than self-serving.

Being an annexationist who’s prepared to give the Palestinians little more than autonomy, Netanyahu is not sincerely interested in reaching a fair and equitable agreement with them. His Zionist Revisionist conception of peace, to which Trump subscribes, is nothing but a sham, a second-rate version of Olmert’s plan.

As Kelly Craft, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, said the other day, the Trump plan is an “opening offer” and not set in stone.

It should be revamped from top to bottom if it is to have any chance of success. But one strongly suspects this will not happen.