Golda Meir, Israel’s fourth prime minister, was an indomitable, single-minded person of unwavering principles singularly devoted to the Zionist cause. Occasionally presenting herself as an amiable grandmotherly figure, she was a tough cookie, possessing a will of steel who brooked no dissent.

Born in Kiev, Ukraine in 1898, she immigrated to the United States in 1906 and settled in Palestine in 1921, when it was a British Mandate. Occupying a succession of increasingly important posts, she attained high degree of respect in Israel’s political circles. Succeeding the late Levi Eshkol as prime minister in 1968, she ended her career after the 1973 Yom Kippur War on a sour note.

Francine Klagsbrun’s massive biography, Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel (Schocken Books), charts the trajectory of her life in magisterial fashion from the Russian Empire to Israel, with stopovers in Pinsk and Milwaukee. Klagsbrun is an impeccable researcher and a penetrating writer, a combination of talents likely to impress even the most discriminating reader.

Golda Mabovitch, whose father Moshe Yitzhak was a carpenter, grew up in a grimy apartment in Milwaukee that seemed luxurious compared to the hovels of Kiev and Pinsk. Exposed to Zionism in an epoch when most American Jews had little or no interest in it, she was mesmerized by the establishment of the first kibbutzim in Ottoman Palestine.

Morris Myerson, whom she married in 1917, did not share her enthusiasm for building a Jewish homeland in Palestine. But he followed her to Merhavia, a small settlement in the Jezreel Valley. She adapted to its primitive conditions, but he could not and rejected its collective lifestyle.

In 1923, they moved to Tel Aviv, where Golda found a job as a cashier in the public works department of the Histadrut, the Zionist labor union. The lowly position was offered to her by David Remez, an up-and-coming Zionist luminary who would be one of her lovers. The third man in her orbit, Zalman Shazar, would be one of Israel’s presidents. Golda’s romantic relationships with powerful men gave rise to rumors that she had slept her way to the top, says Klagsbrun.

In 1924, she gave birth to the first of two children. They lived in poverty for the next few years, the darkest period of her sojourn in Palestine. By this juncture, she and Morris had grown apart. Golda’s prospects improved after her appointment as secretary of a women’s workers’ council. Golda was appointed head of the Histadrut’s political department in 1940 following the death of her predecessor in a car accident.

As Klagsbrun suggests, Golda was a right-wing Zionist who, though not blind to the Arab presence in Palestine, thought that the land belonged to Jews and should not be partitioned.

During the Holocaust, she argued that the primary goal of Zionism was to save Jews imperilled by Nazi savagery. Some of her colleagues did not share this objective. Like David Ben-Gurion, who would be Israel’s first prime minister, she regarded the Irgun’s guerrilla war against the British as irresponsible and inimical to Jewish interests.

Appointed co-head of the Jewish Agency’s political department in the mid-1940s, she was placed in charge of a special committee to determine how much manpower would be needed to face the Arabs in a future war. With this in mind, Ben-Gurion sent her to Amman to sound out King Abdullah of Jordan. He said he would not permit Arab armies to pass through Jordan to invade the Jewish state. Later, Golda met Abdullah again. He told her that Palestine should remain undivided under his rule and that Jews should be content with autonomy rather than statehood.

In 1947, while being driven from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, the car she was in was attacked by Arabs. The man sitting next to her, the director of an organization that cared for young immigrants, was instantly killed and died in her arms, a gory incident she never forgot.

On the eve of the first Arab-Israeli war, she was dispatched on a fund-raising mission to the United States. She raised $25 million, then a considerable amount. American Jews loved Golda.

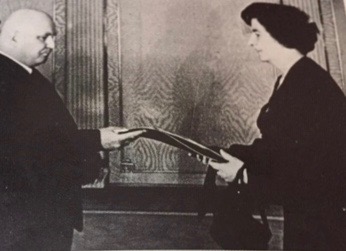

Ben-Gurion, who was very fond of Golda and admired her abilities and strong work ethic, appointed her as Israel’s first ambassador to the Soviet Union, a post she did not particularly desire. She arrived in Moscow during the short-lived honeymoon period between Israel and the Soviet Union. After Jews mobbed her ecstatically during an appearance at the Chorale Synagogue, Joseph Stalin, the Soviet leader, concluded that Jews were disloyal to Mother Russia. As for Golda, she became extremely devoted to the cause of Soviet Jewish immigration to Israel. In 1969, when she was prime minister, she broke radically with Israel’s longstanding policy of secrecy in its dealings with Soviet Jews, “pushing the subject out of the shadows and into the spotlight,” says Klagsbrun.

Much to her satisfaction, Ben-Gurion invited Golda to be minister of labor and social insurance in his cabinet. She built transit camps for new immigrants, paved roads and created an advanced social security system that included old-age pensions, health and unemployment insurance and disability laws.

She initially opposed Israeli contacts with West Germany, but ultimately resigned herself to accepting reparations from the Germans. However, Golda opposed Ben-Gurion’s plan to forge diplomatic relations with West Germany, a painful issue that tore them apart.

Golda succeeded Moshe Sharett as foreign minister in the summer of 1956 and promptly Hebraized her surname to Meir. She was kept out of the negotiations that culminated in Israel’s alliance with France and Britain to invade Egypt in the Sinai War. But she played a key role in forging ties with a succession of countries in Africa and sided with the Africans in condemning apartheid in South Africa.

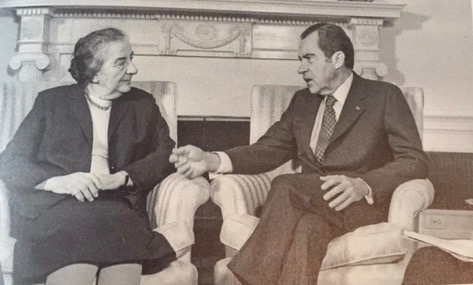

Thanks to a meeting with President John F. Kennedy, she was instrumental in improving Israel’s relations with the United States after the chill of the Eisenhower era. During the Nixon presidency, she convinced the United States to accept Israel’s atomic bomb program on condition that it was kept secret. Klagsbrun describes their understanding as “a historic turning point in America’s attitude toward Israel and the bomb.”

Abba Eban replaced her as foreign minister in 1966, after which she became the secretary-general of the Mapai Party, the forerunner of the Labor Party. According to Klagsbrun, it was the second most important position in Israel.

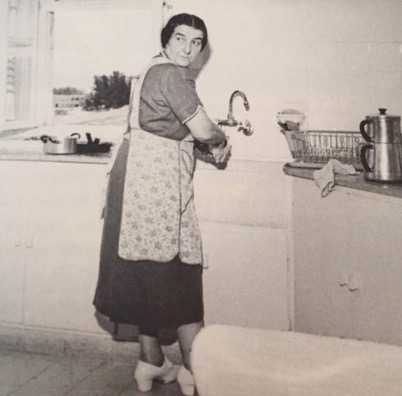

Pinhas Sapir, the powerful secretary-general of the Labor Party, ensured that Golda filled Eshkol’s shoes as prime minister after his death. She and her circle of advisors would meet in her kitchen to discuss the pressing issues of the day. Proposals would then be presented to the cabinet for approval. Critics complained that Golda’s “kitchen cabinet” was undemocratic.

As prime minister, she hewed to the principle that Israel could not return to the pre-1967 borders. “She viewed the (occupied) territories as bargaining chips she could use to arrive at stronger, more secure borders,” writes Klagsbrun. However, she rejected the notion that Israel should keep the entire West Bank (“we don’t want a million Arabs who don’t want us”) and spoke of a withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula. She insisted on keeping East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights.

She had a blind spot about the Palestinians, claiming “they do not exist.” In denying their existence, she opposed Palestinian statehood. “She lacked the foresight to see the rising tide of nationalism among Palestine’s Arabs,” Klagsbrun notes.

When the secretary-general of the Labor Party, Arie Lova Eliav, advocated a two-state solution, Golda eased him out of his job, even though he believed that Palestinian statehood should be linked to an arrangement with Israel’s neighbor, Jordan.

Golda rushed to the aid of Jordan’s King Hussein, whom she met regularly in secret, when Syrian armored units crossed the Jordanian border and occupied the northern city of Irbid in 1970 during the Black September crisis. Israel massed troops on the Syrian frontier and Israeli jets buzzed Syrian tanks in Jordan, sending an unmistakable signal to Syria to withdraw immediately.

She reacted suspiciously to Anwar Sadat’s 1971 peace initiative offering to defuse military tensions with Israel and reopen the Suez Canal if it started to withdraw its army from the eastern bank of the canal. Israel’s pullback would be a first step toward a full withdrawal of Israeli forces from occupied Arab territories and the “restoration of the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people,” Sadat said, subsequently noting that Egypt would be “ready to enter into a peace agreement with Israel.”

As Klagsbrun acknowledges, this marked the first time an Arab head of state had mentioned the concept of peace with Israel. Thought tempted by Sadat’s sweeping proposition, Golda essentially rejected it, setting into motion Sadat’s decision to go to war with Israel in 1973.

On October 6 of that fateful year, Egypt and Syria launched the Yom Kippur War, recapturing territory and inflicting punishing casualties on Israel. With just hours to go before they attacked Israeli lines, Israel’s chief of staff, General David Elazar, made two recommendations that Golda balked at. In accordance with Defence Minister Moshe Dayan’s advice, she neither fully mobilized the reserves, nor did she authorize preemptive air strikes on Egypt and Syria. These catastrophic misjudgments notwithstanding, Golda was like a “rock” during the three-week war, an appraisal that even her severest critics held.

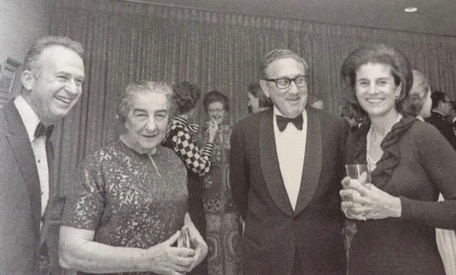

As U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger picked up the pieces in post-war shuttle diplomacy, Golda succumbed to American pressure and agreed to relinquish parts of the Sinai to Egypt. It was the beginning of a protracted process that would lead to Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt in 1979. Before it was signed, Golda rebuked Prime Minister Menahem Begin for agreeing to vacate the Sinai in its entirety, saying that Israel should retain a small portion of it for its own security.

The 1974 Agranat Commission found Elazar and two of his deputies responsible for mishaps that occurred during the war, but the commissioners exonerated Golda and Dayan, a verdict the majority of Israelis considered a whitewash of reality. Although she did not feel blameworthy, she resigned in April. “Five years are enough,” she said in tendering her resignation in a calm 15-minute speech. “I have come to the end of the road.”

Her long political career was over. “She left the Knesset with an overwhelming sense of relief and an enduring sadness,” says Klagsbrun.

Yitzhak Rabin, her successor whom she treated like a son, consulted Golda regularly and often turned up at her home on Saturday mornings to prepare for his Sunday cabinet meetings.

Until almost the end, Golda continued to be “a voice of authority” in the Labor Party and maintained an involvement in national affairs. But as she approached her 80th birthday in 1978, her health declined precipitously. Golda’s lymphoma worsened and she was plagued by a heart condition. She died in Ramat Aviv on December 8 at 4:30 in the afternoon, felled by liver failure, a complication of lymphoma.

In assessing her contribution, Klagsbrun is kind to Golda. “In spite of faults and failures, she left a legacy for Israel, the Jewish people, and the world at large of courage, determination, and devotion to a cause in which one believes, however difficult the course.”