Delivering a lecture in 1979, the German scholar Eberhard Jackel nailed it when he said, “We Germans were liberated from (Adolf) Hitler, but we’ll never shake him off. Hitler will always be with us … He is present — not as a living figure, but as an eternal cautionary monument to what human beings are capable of.”

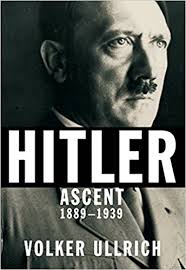

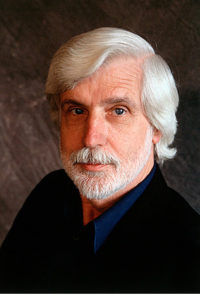

German historian and journalist Volker Ullrich refers to Jackel’s sage words as he launches into Hitler: Ascent, 1889-1939 (Alfred A. Knopf), the first part of a magisterial biography of “the most malevolent person” of the 20th century.

Ullrich’s 998-page book, ably translated into English by Jefferson Chase, is the latest in a line of biographies of the demagogue and mass murderer who stirs up more emotions than any other figure in modern history. Proceeding Ullrich was Alan Bullock’s Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, Joachim Fest’s Hitler: A Biography and Ian Kershaw’s two-volume work, Hitler, 1889-1936: Hubris and Hitler 1936-1945: Nemesis.

Like his predecessors, Ullrich believes that Hitler was guided by a consistent world view — the removal of Jews from Germany and Europe and the conquest of territory in the east.

Ullrich disposes of two misconceptions in chapter one. First, he dispels the rumor, circulated by the former Nazi governor of occupied Poland, Hans Frank, that Hitler was of partial Jewish descent.

Second, he dismisses the idea that Hitler’s personality was deformed by an unhappy childhood and a paucity of motherly love. But he agrees with the theory that the world would have been a far different place had Hitler, an aspiring artist and architect, been accepted into the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

The Austrian capital, he writes, greatly influenced his character and political views. A pan-German sympathizer and radical nationalist, Hitler lived in Vienna from 1908 to 1913. When he arrived in the city, a hotbed of crass racist theories, he was not hostile to Jews. Indeed, he had fond memories of Eduard Bloch, the Jewish doctor who had treated his beloved mother. He sold his paintings to the Jewish owners of picture-framing and art shops. He praised the cultural achievements of German Jews like the poet Heinrich Heine and the composer Gustav Mahler. Yet, in his mind, Jews were always foreigners, a “race unto themselves,” as he would write in his turgid manifesto, Mein Kampf.

By Ullrich’s reckoning, World War I was Hitler’s defining experience. It enabled him, a dispatch runner, to win the Iron Cross, Second Class, for uncommon valor. As he wrote in a letter to a friend, “It was the happiest day of my life.” The war, too, made a career in politics possible for Hitler, a disoriented and disaffected loner who had no real purpose in life.

With Germany’s ignominious defeat, Hitler faced demobilization and the prospect of being plunged back to his insecure pre-war existence. But thanks to an army captain who selected Hitler as an undercover agent to reignite the spirit of nationalism and militarism among his fellow soldiers in the wake of a Marxist revolt and a right-wing counter-rebellion in Bavaria, Hitler found his calling in politics.

“His turn towards fanatical antisemitism, which he would later claim originated in Vienna, actually took place amidst the revolution and counter-revolution in Munich,” says Ullrich. From that point forward, he adds, “the Jew” as the incarnation of evil occupied the center of his racist world view.

Hitler, having believed unfounded accusations that Jews had shirked their duty during the war, was ordered to attend a meeting of the German Workers’ Party in 1919. Hitler joined the party and soon became its leader. “Without Hitler, the rise of National Socialism would have been unthinkable,” he says. “In his absence, the party would have remained one of many ethnic-chauvinist groups on the right of the political spectrum.”

Broadly speaking, it appealed to the lower middle class, national conservatives and antisemites. More specifically, it attracted artisans, small businessmen, shopkeepers, white-collar workers and farmers, but not blue-collar workers.

In his speeches to his followers, Hitler never failed to claim that Jews were intent on ruling the world and that they had to be removed from German society.

Ullrich believes that the failed Beer Hall putsch of November 1923 was a pivotal moment in Hitler’s ascent. If the Bavarian judicial system had enforced the letter of the law, he contends, Hitler would have spent many years in prison for his attempted coup, making a political comeback almost inconceivable. Worse still, he was allowed to use his trial as “a stage for self-aggrandizement.”

Hitler’s brief incarceration in Landsberg prison was a turning point. Although he had toyed with suicide while in jail, Landsberg encouraged his belief in himself and his historic mission to make Germany great again. And it prompted Hitler to compose Mein Kampf, which became a bestseller and made him rich.

By this juncture, Hitler no longer spoke of driving out German Jews, which he demonized as vermin. He was now intent on eradicating them. And in terms of foreign policy, he demanded an abrogation of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, a restoration of Germany’s 1914 borders, a settling of accounts with Germany’s “arch-enemy,” France, the restitution of its overseas colonies, and more “living space” for its expanding population.

Ullrich argues that the Great Depression, which hastened the collapse of the German economy and the Weimar Republic, transformed the Nazi Party into a mass party. By 1931, the Nazis formed the largest parliamentary faction, having won 37 percent of the vote in that year’s general election. In the subsequent election, however, they did not fare as well.

Nonetheless, time was on Hitler’s side. One chancellor after another resigned after failing to steer Germany through choppy waters, and President Paul von Hindenburg decided that a national unity government would be in its best interest. Under pressure, Hindenburg appointed Hitler as chancellor. Conservatives such as Franz von Papen and Erich Ludendorff were convinced they could keep Hitler in check and direct him for their own purposes.

The director of the Central Association of Germans of the Jewish Faith, Ludwig Hollander, was cautiously optimistic as well, assuming that the “inalienable connection” of Jews “to everything truly German” would not be broken by Hitler.

Ullrich attributes the Nazis’ success to “powerful tendencies deeply anchored in German history.” He lists them. An anti-Western nationalism that rejected the ideas of the French Revolution. A belief in conspiracy theories that attributed Germany’s unexpected defeat in the war to stab-in-the-back legends and lies. A strain of antisemitism that permeated virtually all strata of German society.

Hitler’s brilliant abilities as an orator was also a factor in his meteoric rise. “Even intelligent, strong-willed people found it difficult not to be moved and convinced by Hitler,” Ullrich writes. Interestingly enough, he wrote his own speeches.

Until his appointment as chancellor in January 1933, Hitler was always frank about his intentions. With astonishing openness and clarity, he promised to “root out” Marxism — a euphemism for the Social Democratic Party and the Communist Party — and pledged to remove Jews from Germany.

But it was Hindenburg, not Hitler, who initially pushed Germany into dictatorship. Only days after Hitler was named chancellor, Hindenburg issued a decree curtailing the right to free speech and free assembly and subjecting the two left-wing parties to severe restrictions. Within about a month of that development, the first of many concentration camps, Dachau, was opened.

The Nazis consolidated their powers with the passage of the Enabling Act, which was followed by the first boycott of Jewish businesses, lawyers and doctors. By then, physical attacks on Jews had become common in Germany.

In short order, Jews were dismissed from the civil service. This was a watershed, marking the first time a German government had curtailed the legal equality of Jews. “It was the first steep in a gradual process of reversing the legal emancipation of German Jews completed in 1871,” says Ullrich. “There was no place for Jewish Germans … stigmatized as racially inferior.”

With all sectors of cultural life brought under Nazi control, Jews in journalism and the arts — music, film, theater, the visual arts and literature — lost their jobs.

During his first years in office, Hitler was careful in his pronouncements on foreign policy. But eventually, he dropped all pretences of moderation. German troops reoccupied the Rhineland, triggering a wave of euphoria throughout Germany. The Saar region was returned to Germany after a referendum. Compulsory military service was reintroduced as Germany continued to rearm.

As the economy continued to improve and Germany achieved full employment, a mood of optimism swept through the country, bringing with it a cult of popular Hitler worship and the “Heil Hitler” greeting. Hitler, widely regarded like a pop star, portrayed himself as a simple man of the people who led an almost ascetic existence.

Not exactly.

He had a passion for fast and expensive Mercedes cars. He lived in the lap of luxury, exercising an insatiable appetite for Viennese pastries with whipped cream. But he refrained from consuming meat or smoking cigarettes, and he rarely drank. He kept a mistress, Eva Braun, but referred to her as his “private secretary,” kept her under wraps and did not marry her until his final days.

Throughout the 1930s, the Nazi regime continued to remove Jews from what Ullrich calls “the German ethnic-popular community” by harassing, persecuting and attacking them. The Nazis hoped they would emigrate. Many left, but a considerable number remained behind, even after they lost their citizenship with the promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws in 1936.

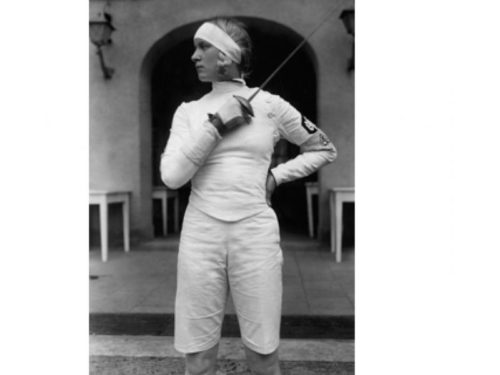

There was a slight reprieve during the winter and summer Olympics, both held in Germany. Antisemitic signs were taken down. The virulently anti-Jewish rag, Der Sturmer, was not delivered to newspaper kiosks. Two token half-Jewish athletes, the ice hockey player Rudi Ball and the fencer Helene Mayer, were selected for the German Olympic team. And the Nazi press stopped assailing the partially Jewish president of the German Olympic Committee, Theodor Lewald.

But once the Olympics were over, the Nazis unveiled a new and ferocious antisemitic campaign accompanied by outbursts of violence. Another wave of antisemitism was unleashed in the early autumn of 1938 as synagogues and Jewish institutions were attacked. On November 9, following the assassination of a German diplomat in Paris at the hands of a young Polish Jew, a nation-wide pogrom broke out, the worst since medieval times. Kristallnacht, as it was known, was portrayed by the Nazi Party press as a spontaneous expression of grassroots outrage, but in fact it was orchestrated by Hitler’s government.

“It is fairly safe to say that the majority of the German populace reacted negatively to Kristallnacht, although their public rejection of the violence was largely based not on empathy with the Jews, but rather on their dismay at the destruction of valuable commodities,” Ullrich writes. “Hitler and his henchmen could consider Kristallnacht a success. They had unleashed antisemitic violence against the Jewish community on a previously unprecedented scale without encountering any resistance. This was a clear sign that the majority of Germans had accepted the exclusion of Jews from the ‘ethnic-popular community,’ even if they had reservations about open brutality.”

During the same year, Austrian-born Hitler annexed Austria in the Anschluss, grabbed the Sudetenland, converted the rest of Czechoslovakia into a German protectorate and successfully demanded the return of Memel from Lithuania.

With these triumphs, Hitler made a shambles of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement toward Germany, which, Ullrich says, was “utterly misguided.”

Emboldened by his string of successes abroad, Hitler reopened the Danzig issue. Danzig, having been incorporated into Poland after World War I, had been renamed Gdansk. But now Hitler hankered for it. Acutely aware that a line had to be drawn in the sand to stop German aggression, Britain and France issued a statement guaranteeing Poland’s independence.

Hitler, buoyed by his victories in Europe, was not impressed and prepared for an invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. “Hitler believed he was at the zenith of his unprecedented career, but in reality his descent had already begun,” says Ullrich. “He had gone down a path that would lead to his own demise.”