Polish journalist Ksawery Pruszynski visited Mandate Palestine in 1933 at the suggestion of his Jewish friend, Mojzesz Pomeranz, a Zionist who would settle in Tel Aviv toward the end of that decade.

Pruszynski, a conservative Pole from an aristocratic family hailing from what is now Ukraine, met Pomeranz when they were both studying law at Jagiellonian University in Krakow. Pomeranz convinced him that a series of articles about the evolving Jewish community in Palestine would be of interest.

During a six-week tour of the country, most of it on foot, Pruszynski visited cities and kibbutzim and met Jews and Arabs. His stories were carried by Slowo, a Polish newspaper in Vilna, and then published in book form in 1936 under the title of Palestyna po raz trzeci, or Palestine for the Third Time.

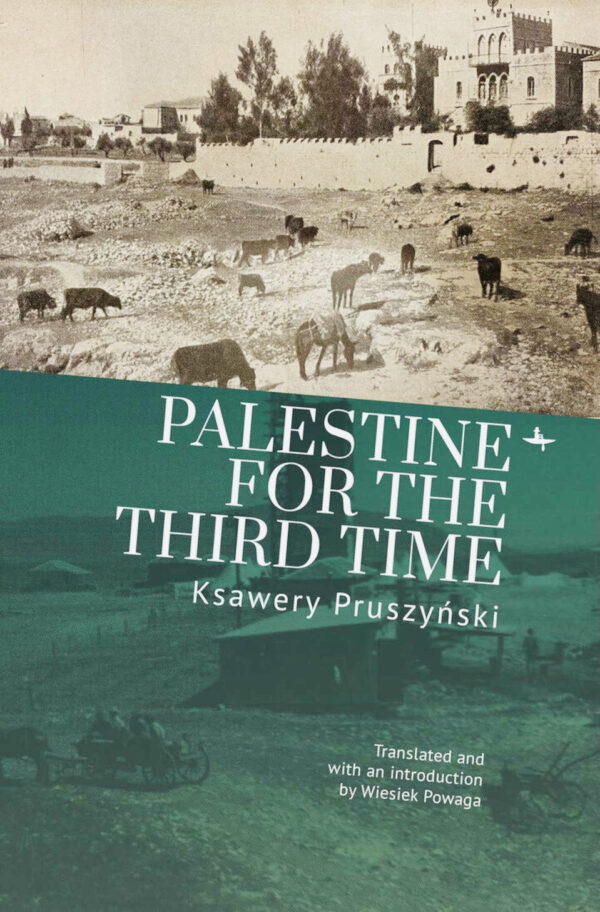

Printed in English for the first time by Academic Studies Press, Palestine for the Third Time is an engaging, empathetic and often perceptive account of the Zionist project in the ancestral homeland of the Jews. Translated into English by Wiesek Powaga, it begins with a foreword by Antony Polonsky, a specialist in Polish history.

According to Polonsky, Pruszynski was dismayed by the growing antisemitism and anti-Ukrainian sentiment in 1930s Poland. Having been raised in a region of diverse cultures and languages, he was sympathetic to the traditions of the old pluralistic Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

And as Powaga writes in the introduction, he supported the work of the Zionists in Palestine. As the citizen of a nation that had lost its sovereignty and independence after being partitioned by foreign powers, he empathized with the desire of Jews to resurrect their ancient homeland.

Following World War II, Pruszynski was employed as an advisor to Poland’s mission at the United Nations. The Polish ambassador, Oskar Lange, invited him to join the new Ad Hoc Committee for the Palestinian Question, a branch of the UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP).

Pruszynski believed that “the Jews deserved a state of their own, while fully aware that the festering Arab-Jewish conflict required some kind of guarantee for the rights of the Palestinians,” says Powaga. In accordance with this belief, his subcommittee recommended the partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. “He worked tirelessly in support of this plan,” Powaga adds.

Pruszynski’s pro-Zionist views appear in the foreword of Palestine for the Third Time. “The fact that three million Jews live in Poland today provides justification for addressing this issue,” he writes. “Whether we like it or not, we cannot remain indifferent to their aspirations, nor can they ignore what we think about them. Poland seems to be a highly suitable vantage point from which to observe the efforts of this new country, which now, before our eyes, is entering history, and not for the first time.”

Shortly after his arrival in Palestine, he is standing on the balcony of Poland’s consulate high above Tel Aviv. His host, Bernard Hausner, is the consul of the Polish republic. (Hausner, a rabbi, was the father of Gideon Hausner, the prosecutor at Adolf Eichmann’s war crimes trial in Jerusalem in the early 1960s).

“Below, Tel Aviv spread before us in a wide swathe of white houses and streets caught between Jaffa Bay and the green belt of orange groves,” Pruszynski writes. He goes on: “Everywhere, here and as far as the eye can see, building sites … patches of sand, white piles of cement, the concrete pillars of future houses …”

To Pruszynski, Palestine radiates prosperity. “Unemployment is unheard of … there is a shortage of labor … despite the availability of Arab workers … and a well-regulated quota of labor immigration and … a fairly sizeable constant flow of ‘tourists’ who come and then decide to stay for good.”

Compared to the economic woes besetting other countries during the Depression, Palestine “feels like an oasis.” Palestine again is “a land flowing with milk and honey.” Yet poverty is endemic, he notes.

In his judgment, Jews come here for “an idea, just like they go to America for wealth.” The “idea” is followed by “sold capital, given with noble intentions by rich magnates” like the Rothschilds. “Palestine is a classic example of how great things can be achieved through a combination of big money and the right people.” In his view, Jewish immigration and capital have “dragged” Palestine from feudalism to capitalism.

He is amazed by the development of the country. “Some thirty kilometres south of Jaffa, a more or less solid stretch of settlement begins. It is the richest part of Palestine, the pardes region, and it is mostly privately owned. It circles around Tel Aviv and climbs through Petah Tikvah and Herzliya toward French Syria.”

And yet some new Jewish immigrants, like a doctor from Poland he met who was assailed by antisemitic thugs, feel “unsettled and insecure” here.

He evinces admiration for Russian Jews who endured hardships after arriving here, describing them as “tough and resilient.” And he stands in awe of the Zionist campaign to drain malarial swamps and replace them with orange groves. Pruszynski, too, is impressed by the reemergence of Hebrew.

As he surveys the achievements of the Zionist movement in Palestine, he argues it has given Jews, “this great, historically rich nation, a new political direction.” In a prescient observation, he writes, “It may be the beginning of a portentous change, fraught with consequences that will be felt not just in the Middle East, but everywhere else where Jews live in the world.”

Of the 200,000 Jews in Palestine, 45,000 are workers, he says. Most of them are members of the Histadrut, the labor federation. “With its network of branches, an efficient bureaucratic apparatus, and large financial resources, the Histadrut is indeed a power in the land.”

He visits Merhavia, a kibbutz, and compares it to a “typical Polish manor.” He is struck by the Christian appearance of the children. “All all are flaxen-haired blond with cornflower blue, Slavic eyes. They could easily be taken for Germans … A weird transformation. Observing the parents, I notice that they, too, look somehow different from the usual physical Jewish type of the Diaspora. Perhaps it is the effect of the sun, manual work, different climate? Whatever it is, these people have changed since they left their native Tarnows, Rzeszows or Jaslos.”

At another kibbutz, Gesher, he learns that the banana fields were burned by the sun, forcing the kibbutzniks to plant orange trees, which have flourished. Nonetheless, some have found employment in the nearby Rutenberg power station, “the biggest capitalist industrial colossus in Palestine.”

Visiting Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall, or Western Wall, he calls it “a symbol of endurance and survival,” although it’s in “pitiful” condition and in ruins. He reaches it by walking through the “narrow, smelly streets of the Arab town.”

In a conversation with an “Arab friend” and his companions, he learns that Arabs are afraid that Jews will become a majority in Palestine. His Arab interlocutors do not believe that Jews and Arabs can form a “common position” against the British authorities, yet he thinks, incorrectly, that constructive negotiations between Zionists and Palestinian nationalists are possible. Pruszynski is of the opinion that Britain plays Jews against Arabs to tighten its foothold in Palestine.

In his view, Palestine and Transjordan can absorb three to five million Jews. “These are not overly optimistic estimates,” he says. “They are, if anything, too low.” He is right, of course.

He claims that Soviet representatives in Palestine are trying to provoke the Arab masses against Jews. “The main force waging war against the rebuilding of the State of Israel — relentless, constant, now and in the future — is Soviet Russia. It reckons that it is better to win over millions of Arabs than 200,000 Palestinian Jews …”

Peering into the future, Pruszynski miscalculates when he says, “The Palestinian project is not threatened by Arab daggers, but by Soviet cannons,” and when he claims that “the Soviets have turned out to be the most dangerous enemy of the Jews.”

Pruszynski learns that Polish exports such as textiles, timber and potatoes are pouring into Palestine, and that Polish Jewish immigrants account for a high proportion of the Europeans settling here.

“I do not think that even the worst antisemite convinced of the harm inflicted by Jews on Poland cannot deny that, as far as Palestine is concerned, there is no conflict. Even if he assumes that Jews are an undesired element in Poland, he should greet with satisfaction the fact that of all Diaspora countries Poland has the strongest emigration movement And the weakest when it comes to export of capital.”

In his afterword, Pruszynski admits that his traditional upbringing instilled in him “many gentile, even feudal, customs which I knew to be foreign, if not hostile, to Jews, yet which I accepted … All this did not make me close to Jewish culture, nor did it teach me to understand it.”

Nevertheless, he condemns “hotheaded” Poles and “nationalistic” Polish university students who maintain that antisemitic intimidation and emigration are the best ways of solving the ‘Jewish problem’ in Poland.

“My civic instinct told me that finding a solution to (it) in Poland was badly needed, necessary even.” Pruszynski, however, believes that Jewish emigration will surely affect Polish-Jewish relations. He admits that “probably no one in Poland, with the possible exception of the socialists, wishes for the assimilation of the Jewish masses.” He contends that assimilation is not in the Jewish national interest and that Zionism is the “most effective dam” against it.

In closing, he credits Palestine with having been a fount of three seminal events — the birth of Christianity, the emergence of the Crusades, and now, the resurrection of a Jewish homeland.

“What happened in this small and seemingly insignificant country (has) had worldwide resonance,” he muses. “I have a feeling that one day soon the consequences of the Zionist renaissance will rank in the same order of magnitude as Palestine’s previous two entries into world history.”

Pruszynski’s prophecy is dead on.

In the wake of Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939, Pruszynski worked with Wladyslaw Sikorski, the prime minister of the Polish government-in-exile in London, and was press attache at the Polish embassy in the Soviet Union. Unlike some of his Polish contemporaries, he called for a rapprochement with the Soviet Union, which occupied eastern Poland shortly after Germany’s invasion.

Returning to Poland in 1945, he was appointed councillor of the Polish embassy in Washington. He then headed one of the subcommittees of the UN Special Committee on Palestine. In this capacity, he delivered two speeches on the growing conflict in Palestine.

“There is something unique in the way this great nation, the Jewish one, made a religion of their longing for their lost home,” he declared in his first speech on November 25, 1948. “We, Polish people, have special reasons to promote the State of Israel. We have fought for too long time for a state of our own not to understand such a fight … We have a common debt towards the nation which gave so much to the world and was so badly repaid, and it is now the moment to repay this thousand year-old debt.”

Four days later, Pruszynski delivered his second speech.

“Poland has a particular interest in Palestine,” he said. “The reasons for this interest are altogether different from those assumed by Arab representatives. They are wrong to think that Poland views a Jewish state in Palestine as a kind of reservoir into which it can channel its own ‘inconvenient’ Jewish population.”

Pruszynski explained that “the Jewish cause” was dear to Poland’s heart precisely because of its antisemitic sins. “Our nation was the closest living witness of the terrifying mass murder carried out by Germany on the Jews. My country was the place of these executions — and this is why the fate of the Jews has shaken us to the core. It is that past, and that fate, which has stirred in us this conviction that a nation for centuries deprived of its motherland has to have a motherland to return to, that has to find its home.”

Concluding his speech, he said, “No other nation understands better than the Polish nation the longing for one’s own land, the land that belonged to one’s ancestors … This is the reason why the Polish nation understands the struggle of Palestinian Jewry.”

Shortly afterward, Pruszynski was appointed Poland’s ambassador to the Netherlands. Polonsky believes his new job was a demotion: “The Soviets seemed to have disapproved of his strongly pro-Israel stance at the United Nations.”

With the intensification of the Cold War, Pruszynski’s position as a diplomat became increasingly tenuous. He decided to return to Poland, but en route to Warsaw, he was killed in a car accident in Germany on June 13, 1950.

He was six months shy of his 43rd birthday.