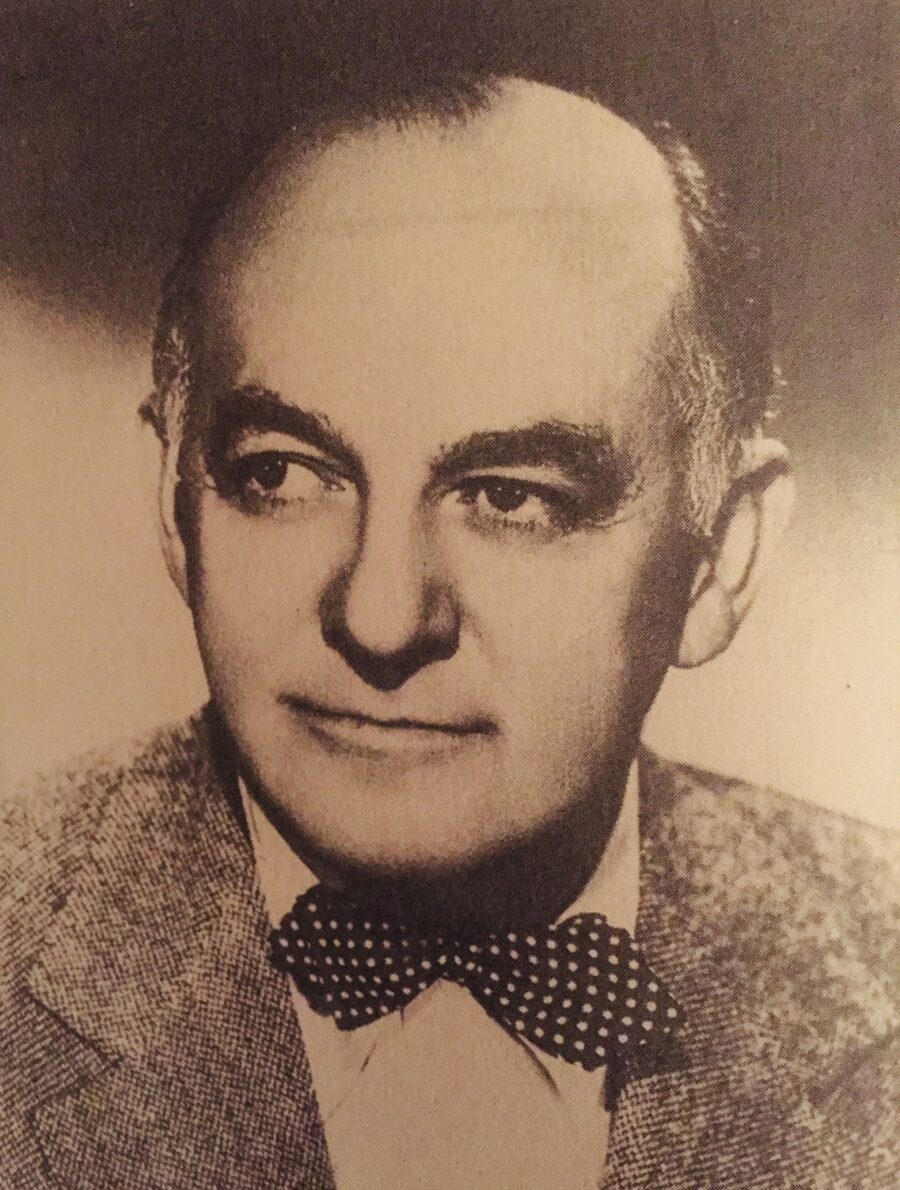

Harry Cohn, the chief executive officer of Columbia Pictures from 1932 until his death in 1958, prided himself on being unique. Regarded as the youngest Hollywood mogul, he was also the only president of a major studio who was head of production.

In addition, he had the most diverse background of any of his contemporaries, having been a pool hall hustler, trolly car conductor, nickelodeon performer, song-plugger, musical shorts producer and travelling exhibitor.

Yet, as Bernard F. Dick observes in The Merchant Prince of Poverty Row: Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures (University Press of Kentucky), a perceptive account of his career, Cohn’s real claim to uniqueness lay outside the boundaries of the movie industry. To this day, he is still the one and only Jewish mogul who was both bar mitzvahed and baptized.

A late convert to movies, he was almost 30 when he began taking the medium seriously, and he was 40 when he took command of Columbia Pictures.

Born in New York City in 1891, the son of Russian immigrants, Cohn was younger than any of his peers — Carl Laemmle, Adolph Zukor, Joseph Schenck, William Fox, Samuel Goldwyn and Cecil B. De Mille — and was among the Jewish founders of the Hollywood film industry.

Although he was unusually uncouth, as well as a notorious philanderer who supposedly bedded down a long list of starlets, his taste in film was generally refined.

“He could look back at his films and take pride in knowing that many were among the greatest of the American screen: Platinum Blonde, It Happened One Night, Twentieth Century, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington and The Jolson Story,” writes Dick, a professor emeritus of communications and English at Fairleigh Dickinson University and an authority on Hollywood lore.

As Dick points out, Columbia Pictures was an anomaly. While rival studios could easily be categorized — MGM, Universal, Fox and Paramount were respectively known for family fare, low-budget horror and comedy and highbrow and sophisticated dramas — Columbia was eclectic. Its movies ran the gamut from Three Stooges shorts and the Blondie series to All The King’s Men, Born Yesterday and From Here To Eternity, which won no less than a dozen Academy Awards in four years.

Columbia Pictures also made None Shall Escape, a 1941 Holocaust drama which included a scene in which Polish Jews were herded into cattle cars en route to their deaths.

Cohn was a penny pincher “At Columbia, a movie could be made for less than what Fox spent on sets … Even in the early 1930s, when Columbia was struggling to become one of the majors, budgets were uncommonly low.”

Unlike the Big Five — MGM, Fox, Warners, RKO and Paramount — Columbia did not have a theater chain. Yet talented directors, notably Frank Capra, and gifted screenwriters, including Sidney Buchman, Robert Riskin, Ben Hecht and Donald Ogden Stewart, were employed there.

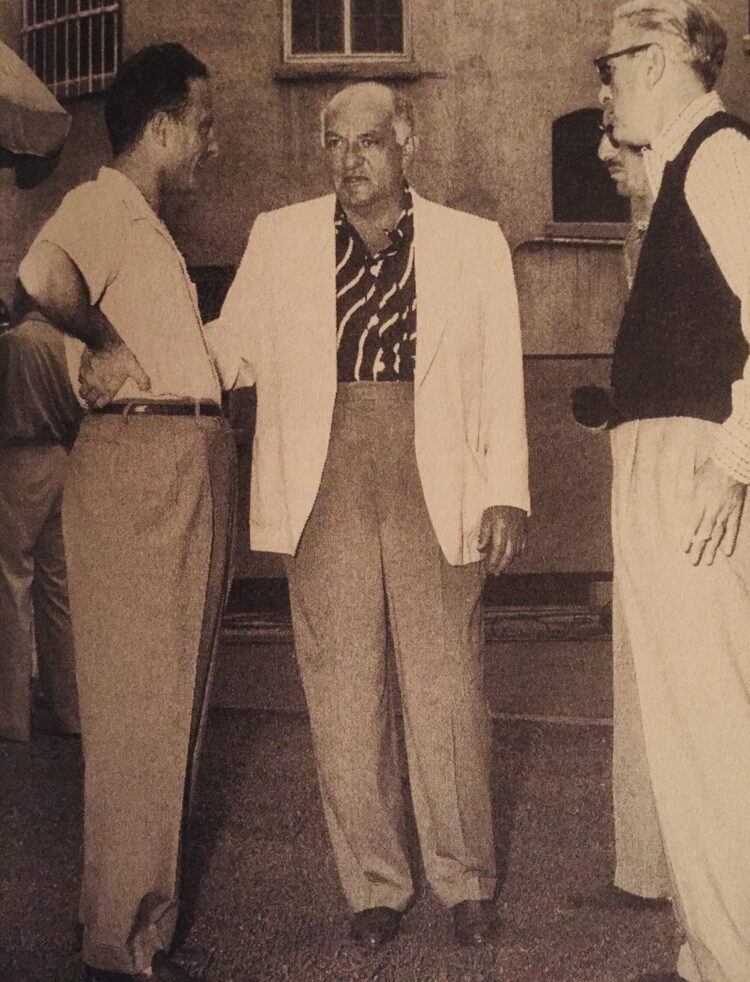

Tyrannical and foul-mouthed, Cohn projected the unflattering image of an overbearing mogul who had to be boss. He was so impressed by Benito Mussolini’s magnificent office in the Palazzo Venezia during a visit to Rome in 1933 that he duplicated it, minus the mosaics and reliefs. A visitor approaching his desk would notice that it was elevated on an eight-inch riser so that Cohn would be looking down at his guest.

“Cohn had the knack of finding a person’s vulnerable spot,” says Dick. “If he sensed weakness, which he despised, he would not relent until he destroyed every vestige of the person’s self-worth. If one retaliated or showed some mettle, Cohn often backed down. Still, dealing with him was an ordeal.”

He died of a heart attack in the winter of 1958 while vacationing in Arizona. His wife, Joan Perry, a minor actress whose likeness appeared as a torch-bearing woman in Columbia films, had him converted to Catholicism. Perry, who married Cohn in 1941, claimed he had uttered the name of Christ before he died.

Dick is skeptical. “Although Cohn never seems to have evidenced any interest in Catholicism, Mrs. Cohn must have convinced the priest that he did.”

Perry choose a Sunday for Cohn’s memorial, as befitting a new addition to the faith. The ceremony took place at two Columbia soundstages that workmen had transformed into a chapel. “There was nothing about the service to suggest that the deceased had been born a Jew,” says Dick.

Among the honorary pallbearers at his funeral were the actors Tony Curtis, Spencer Tracy, Dick Powell and Jack Lemmon. Danny Thomas, a Catholic of Lebanese descent, read the twenty-third Psalm, while Danny Kaye delivered the eulogy the screenwriter Clifford Odets had written.

More than six decades after Cohn’s passing, Columbia Pictures still stands. Coca-Cola bought it in 1982 and sold it to Sony in 1989.

The new ownership and the change of name to Columbia Pictures Entertainment notwithstanding, Columbia will always be associated with the larger-than-life mogul who ran it for a quarter of a century during Hollywood’s golden era.