The United States, Israel’s chief ally, has launched a campaign that could realign the political landscape of the Middle East.

In what could be a diplomatic coup as significant as the United States’ successful drive to end Israel’s state of war with Egypt in 1979, Washington is making a concerted effort to normalize Israel’s relations with Saudi Arabia.

Last week, President Joe Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, visited Saudi Arabia for the second time in three months to gauge the prospects of nailing down such a landmark agreement, but he returned to Washington empty handed.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Saudi Arabia in January, but he, too, fell short of achieving this elusive objective.

Nevertheless, Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen claims that Israel is closer than ever to forging a historic normalization deal with the Saudis. “We are the closest we have ever been to a peace agreement with Saudi Arabia,” he said on July 31 without elaborating.

Late last month, the director of the Mossad, David Barnea, visited Washington to discuss this issue. He met Sullivan and three of his associates: Brett McGurk, the coordinator of U.S. policy in the Middle East; Amos Hochstein, Biden’s advisor on energy and infrastructure and the broker of Israel’s maritime border agreement with Lebanon last year, and Bill Burns, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Barnea did not issue a statement following his talks with these senior officials, but a White House spokesman said the United States and its regional partners are working toward that goal.

Tzachi Hanegbi, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s national security advisor, told reporters yesterday that the road to reaching an Israeli-Saudi normalization agreement is long yet possible. But in a caveat, he added, “Israel will not give in to anything that will erode its security.”

And here lies the nub of the problem.

Is the Israeli government, the most right-wing since statehood 75 years ago, really prepared to make the kind of political and territorial concessions that would entice Saudi Arabia — the seat of Islam and the custodian of the holy Muslim cities of Mecca and Medina — to sign a peace accord with Israel?

Saudi Arabia demands concrete progress toward a two-state solution to resolve the gnawing issue of Palestinian statelessness, but Israel regards the West Bank as an integral part of its territory and Palestinian statehood as a dire threat to its security. In accordance with this outlook, Netanyahu and his coalition allies have been expanding existing Israeli settlements in the West Bank, thereby incrementally dooming the possibility of an independent Palestinian state.

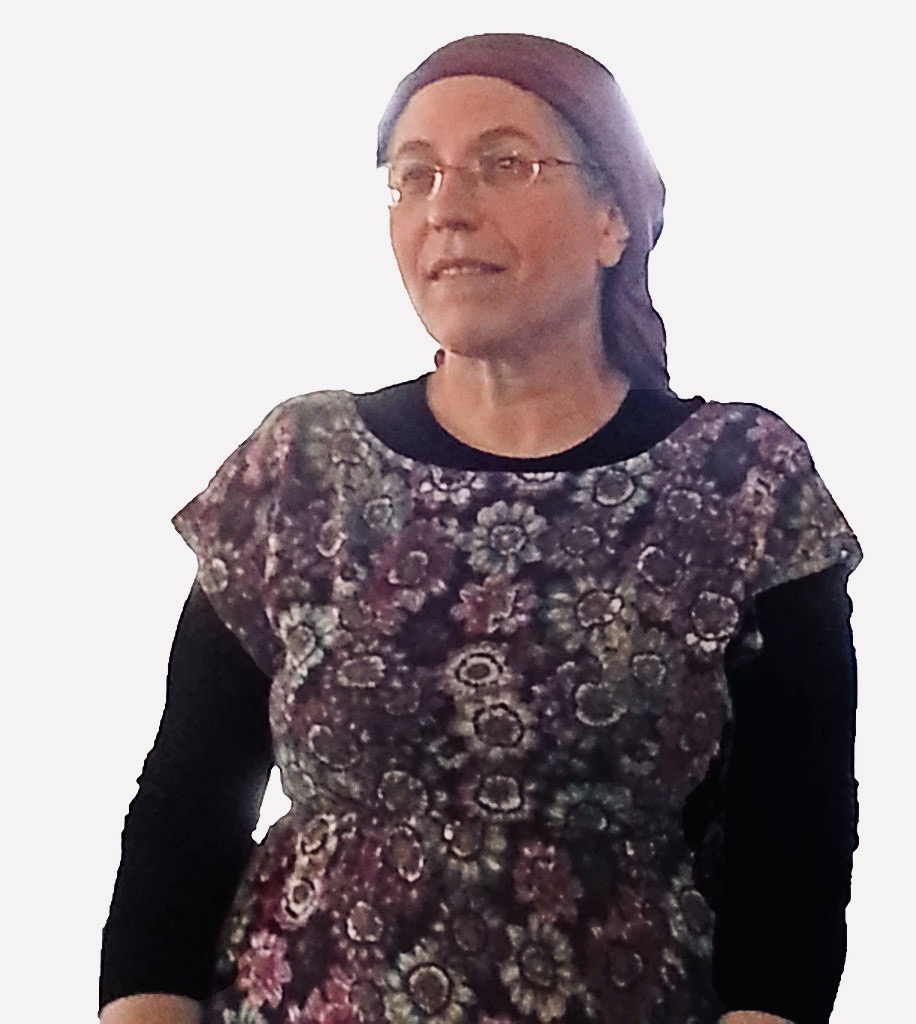

One of the members of Netanyahu’s cabinet, National Missions Minister Orit Struck of the Religious Zionist Party, said that she and her colleagues will not grant concessions to the Palestinians. As she put it recently “We are done with withdrawals. We are done freezing settlements in Judea and Samaria. This is the consensus among the entire right wing.”

Struck was not mincing words. Like Struck, Netanyahu is a right-wing Zionist who abhors territorial compromise — the diplomatic formula that, in theory, would allow the Palestinians to form a sovereign state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

At the same time, Netanyahu realizes that an Israeli rapprochement with Saudi Arabia would be of stellar strategic importance in Israel’s quest for regional acceptance and legitimacy.

Two months ago, he described an Israeli-Saudi normalization pact as “a quantum leap forward” that would upend the region in geopolitical terms. “It would fashion, I think, the possibility of ending the Arab-Israeli conflict,” said Netanyahu, who has called Saudi Arabia the most influential country in both the Arab and Muslim worlds. “And I think that would also help us solve the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.”

On July 30, Netanyahu had Saudi Arabia in mind when he disclosed that Israel is considering building a railway line from Kiryat Shemona to Eilat, and that it could eventually connect Israel to Saudi Arabia.

An agreement with Saudi Arabia would expand the 2020 Abraham Accords, under which the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan agreed to normalize relations with Israel after it dropped its plan to annex the Jordan Valley and Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

For Netanyahu, the Abraham Accords were a monumental step forward because he managed to decouple the burning Palestinian issue — an exceedingly popular one in the Arab world — from the normalization process with four Arab countries.

The Saudis tacitly supported the Abraham Accords, which were brokered by the United States during Donald Trump’s presidency But the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, refused to come on board unless the Palestinian question is satisfactorily resolved.

Judging by the most recent reports, Saudi Arabia, at a minimum, is demanding a promise from Israel to desist from annexing the West Bank, expanding Israeli settlements, building new ones, or legalizing unauthorized outposts. As well, Saudi Arabia is demanding the transfer of some Palestinian-populated land in Area C of the West Bank, which Israel controls, to the Palestinian Authority.

It is highly doubtful whether this Israel government would meet these conditions, much less agree to full-fledged Palestinian statehood further down the road.

In exchange for normalizing relations with Israel, Saudi Arabia is demanding a stiff price from the Biden administration: a defence treaty with the United States, the sale of F-35 fighter jets and advanced missile-defence systems, and a civilian nuclear program.

Apart from its interest in brokering an entente between Israel and the Saudis, the United States hopes to persuade Saudi Arabia to end its participation in the protracted war in Yemen, to lower its oil prices, to draw away from its increasingly close relationship with China, and to join a front against Iran.

In the meantime, the Biden administration is working overtime to convince the Saudis that a deal with Israel would be in their national interest.

If Netanyahu ever decides that normalization with Saudi Arabia is more important strategically than clinging to the West Bank, he would have to be ready for serious political turbulence.

First, he would have to scrap his his alliance of convenience with the Religious Zionist Party and the Jewish Power Party, which are respectively headed by Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich and National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir.

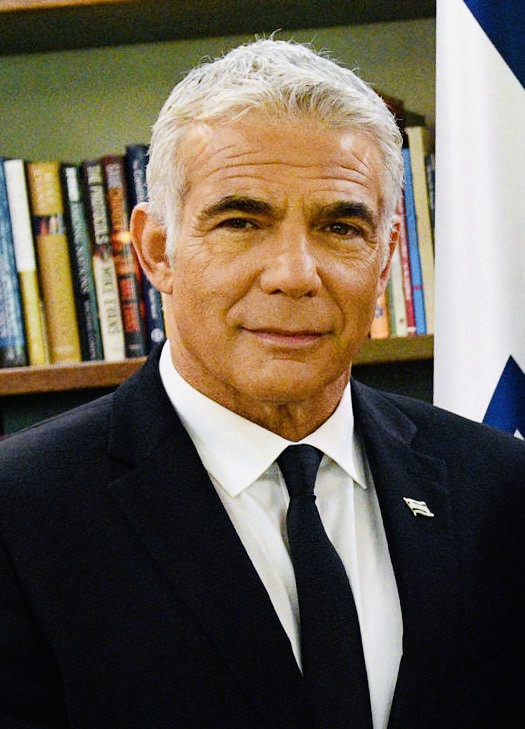

Second, he could attempt to cobble together a coalition with centrists like Yair Lapid and Benny Gantz, both of whom briefly served in his previous governments as minister of finance and minister of defence.

Realistically, this scenario is unlikely to materialize because neither Lapid nor Gantz trust Netanyahu, having been burned by him in the past. Gantz has pledged never to sit in another Netanyahu-led government. Lapid has said he is prepared to join a Likud coalition, but not while Netanyahu is its leader.