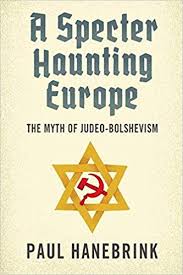

With the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia a fait accompli, Jews were tarred with the accusation that they had fomented and directed it. “Judeo-Bolshevism — the idea that Jews had created and supported Bolshevism and were therefore responsible for its crimes — was an explosive charge that had dangerous and often lethal consequences for Jews across Europe,” writes Paul Hanebrink in his superb book, A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-Bolshevism (Harvard University Press).

Partly as a result of the upheaval in Russia, pogroms broke out in Ukraine and Poland, Hungary passed Europe’s first antisemitic law, and Adolf Hitler launched a campaign against German Jews that culminated with the Holocaust. And the list goes on and on.

Communism in Europe has been swept away, but the belief that it was a global conspiracy hatched by Jews to destroy Western civilization and the Christian order remains intact to this day. Throughout the 20th century, as he notes, it was an ideological staple in counter-revolutionary, anti-democratic and racist circles.

Hanebrink, an associate professor of history at Rutgers University, argues cogently that the Judeo-Bolshevism peril was constructed from “the raw materials of anti-Judaism, recycled and rearranged to meet new requirements.” It rested on the assumption that Jews and Judaism were associated with heresy, misrule and social disharmony and an international Jewish conspiracy, as maliciously outlined in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a Czarist forgery.

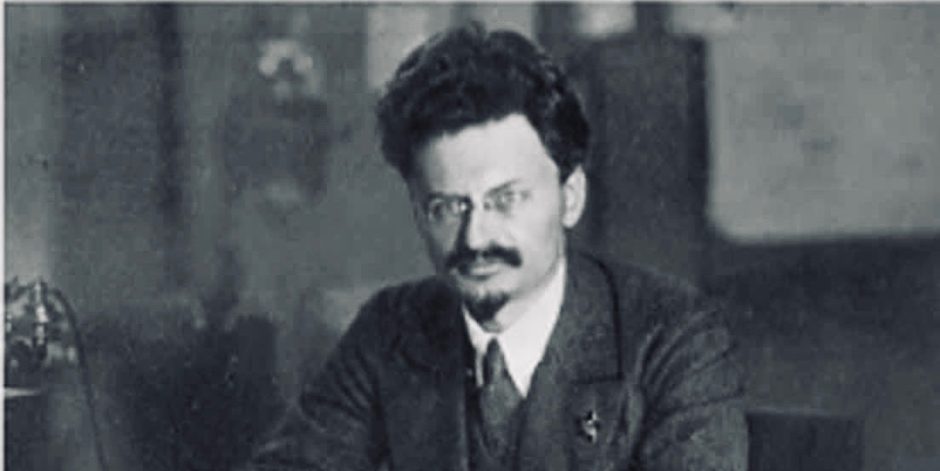

It is true, however, that a disproportionate percentage of Jews were found in the leadership of the Communist movement in various countries: Lev Bronstein (Trotsky) in Russia, Bela Kun in Hungary and Rosa Luxemburg in Germany. But as Hanebrink correctly notes, they were Jews only by birth and not by conviction or practice. And in Russia, in particular, many more Jews were Zionists and Bundists than Bolsheviks.

Nonetheless, the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism grew tremendously, with Trotsky — the founder and commander of the Red Army — often being the face of the Bolshevik Revolution. To counter-revolutionaries, Trotsky represented Jewish power sweeping away traditional authority, an alien force ruling Mother Russia.

“Judeo-Bolshevism received old anti-Jewish themes of disorder, conspiracy, and fanaticism and reshaped them into a critique of Bolshevism that was broadly persuasive, and not only to those who stood on the fringes of the far right,” says Hanebrink.

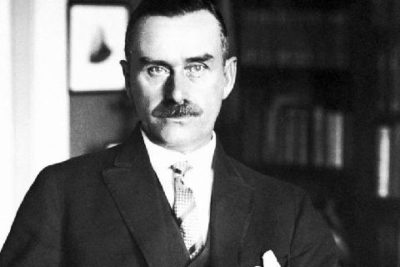

Consequently, this notion was embraced by, among others, Robert Lansing, the U.S. secretary of state; the British politician Winston Churchill, who observed that Jewish revolutionaries had “gripped the Russian people by the hair of their heads,” and the German novelist Thomas Mann, who wrote in his diary that the “Russian Jewish type” stood in the forefront of international revolution.

Fear of the Judeo-Bolshevist threat fuelled pogroms in Eastern Europe that claimed the lives of thousands of Jews and shaped right-wing politics in Poland, Hungary and Romania. In Poland, for example, the specter of Judeo-Bolshevism was an article of faith among rightist politicians and their supporters. They believed that Jews had backed the Red Army during the Polish-Soviet War and that Jews exercised undue influence in the Soviet Union.

“Judeo-Bolshevism reflected anxieties about fragile national sovereignty,” says Hanebrink. “It embodied fears of internal and external enemies. And it was an argument used to rationalize violence, making incidents internationally condemned as violations of humanitarian norms into legitimate acts of national self-defence.”

According to Hanebrink, Judeo-Bolshevism was bound up with Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. Jewish revolutionaries were involved in the rebellions that convulsed southern Germany in 1918 and 1919, and Hitler harped on this to justify his claim that Jews posed a threat to German society.

During the 1920s, he adds, the presence in German cities of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe triggered speculation that they had brought “revolutionary destruction” with them.

Among Spanish right-wingers in the 1930s, Judeo-Bolshevism was lumped together with liberalism and republicanism.

As Germany prepared to invade Poland in 1939, the Wehrmacht prepared guidelines for troop conduct. Soldiers were instructed to carry out “ruthless and energetic measures against Bolshevik agitators, partisans, saboteurs (and) Jews.” Reinhard Heydrich, a top SS official, said, “It goes without saying that cleaning actions primarily apply to Bolsheviks and Jews.”

During the German occupation of Poland, a propaganda campaign equated Communism with Jews, long a theme in Polish nationalist politics. After the Germans captured eastern Poland from the Red Army, a succession of pogroms took place, killing upwards of 24,000 Jews. “German invaders encouraged and provoked acts of ‘revenge’ against Jewish Bolshevik oppressors,” says Hanebrink. Jews, in effect, were accused of having welcomed the Soviet occupiers and collaborating with them.

“In fact, most Jews had never been Communists, and many had also suffered miserably under Soviet Communist rule,” he states. The truth is that the Soviets recruited allies from all ethnic groups.

Germany’s ally, Romania, drew similar parallels. As the Romanian army massed to take back Bessarabia in 1941, Romania’s leader, Marshal Ion Antonescu, ordered the general staff to “identify all Yids and Communist agents or sympathizers” along the Soviet border. Later that year, 4,000 Jews were killed in a pogrom in the city of Iasi.

In post-war Eastern Europe, the Jewish descent of certain leading Communist functionaries was damning evidence that the Soviet occupation was ultimately a Jewish plot. These figures included Jakub Berman, the head of the secret police in Poland; Matyas Rakosi, one of the leaders of the Communist Party in Hungary, and Ana Pauker, the foreign minister of Romania. But as Hanebrink points out, Jews were soon systematically removed from Communist leadership posts.

A special commission formed by the Roman Catholic church to investigate the 1946 pogrom in the Polish city of Kielce claimed that Jews were responsible for the violence because they were “the main propagators of Communism in Poland.”

Poland’s primate, Cardinal August Hlond, condemned the pogrom, but blamed Jews in “great measure” because of their prominence in the Communist regime.

Decades later, the Judeo-Bolshevism trope appeared in West Germany during the so-called historians’ debate of the 1980s, when the historian Ernst Nolte argued that the role Jews had played in Communist parties throughout Europe had decisively shaped Hitler’s worldview.

In Romania, the rehabilitation of Antonescu as an icon of national integrity fed into his discourse that Judeo-Bolshevism threatened the nation.

Judging by its durability, it’s clear that Judeo-Bolshevism is like classic antisemitism — a malleable concept that has adapted itself from one place and time to another, much to the misfortune of Jews.