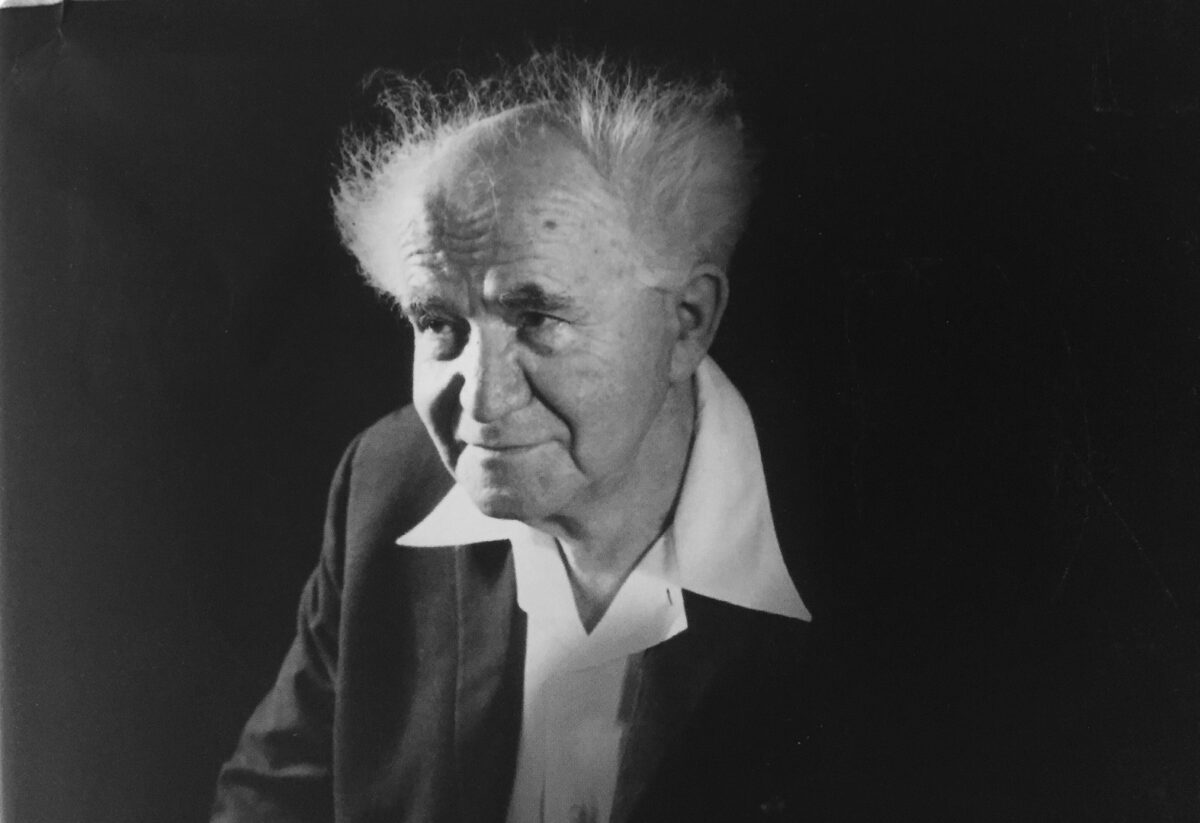

David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first and perhaps greatest prime minister, was a man of conviction.

As Tom Segev observes in his comprehensive and excellent biography, A State At Any Cost: The Life of David Ben-Gurion (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), “The Zionist dream was the quintessence of his identity and the core of his personality, and its fulfillment his greatest desire.”

Describing Jewish statehood as “recompense” for the murder of six million Jews during the Holocaust, he did not take credit for the founding of Israel, but he led this historic process and was willing to pay almost any price to attain it.

Ben-Gurion, however, was not fanatical by any means. Usually finding himself in the center of Zionist and Israeli politics, he was prepared to make tactical concessions and pragmatic compromises in the interests of advancing the cause.

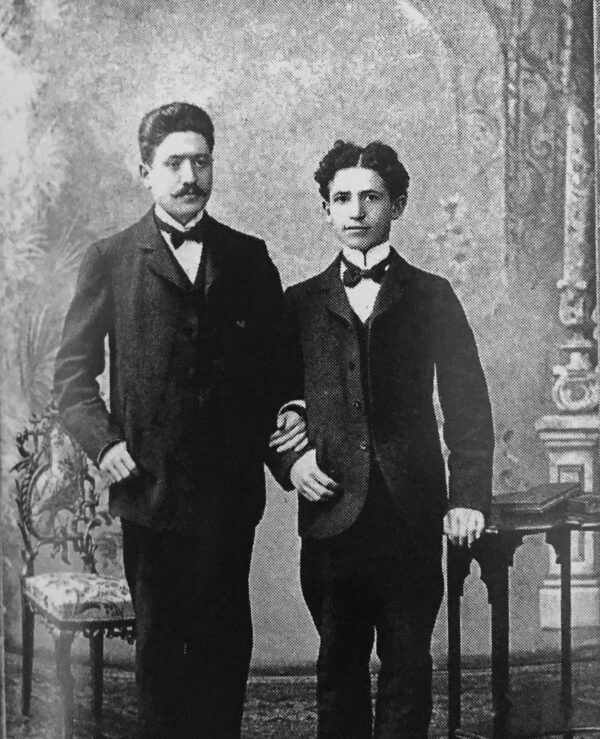

Hailing from Plonsk, a small Polish town 45 miles west of Warsaw, he was born in 1886 into a middle-class family. Named David Gruen at birth, he changed his surname to Ben-Gurion several years after his arrival in Palestine. It was an accepted practice at the time, designed to break with the Diaspora and create a new Hebrew identity.

A fervent Zionist, he immigrated to Palestine, an Ottoman backwater, in 1906. He arrived in Jaffa nine days after leaving Odessa. The majority of newcomers, largely from Russia, entered the country as tourists and usually stayed on illegally.

When he landed, 30,000 Jews lived in Palestine, representing eight percent of its population.The majority were Sephardim. The rest were Ashkenazim who depended on overseas funds to survive. Conditions were difficult and most new immigrants left after a while. Yet he exuded optimism. “Twenty five years from now, we will live in one of the most flourishing, beautiful and happy of countries,” he wrote in an effusive letter to his father.

Unimpressed with Jaffa, which was congested, smelly and noisy, he made his way by donkey to the Zionist settlement of Petah Tikvah. A significant proportion of its residents were ultra-Orthodox and spoke Yiddish. He found employment in an orange grove, but when he was not working, he suffered from hunger.

Ben-Gurion believed that the Land of Israel belonged to the Jews, despite the fact that it was mostly populated by Muslim and Christian Palestinian Arabs.

Within several years, he became a labor organizer, dedicated to the task of replacing Arab laborers with Jewish ones. Only then could Jews establish a separate Jewish economy, free of exploitation, and become a “normal people,” he claimed.

In 1908, he settled in Sejera, a Jewish village in the Galilee. He spent 13 months there, later saying it had been his most profound experience.

At this point, he regarded himself as a loyal Ottoman citizen, thinking that Zionist interests could better be furthered by loyalty to the empire.

During this period, he and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, a future president of Israel, co-authored a book about the connection of Jews to the Land of Israel. They claimed that the Arab peasant farmers of Palestine were actually the descendants of Jews who had lived there before the Arab conquest. This was proof that Jews had never left their homeland and were not interlopers in Palestine, they wrote.

In the waning months of World War I, Ben-Gurion joined the British army. He trained in Canada, but was not sent to the front lines in Europe. Returning to Palestine, he was appointed secretary of the Histadrut, the principal labor union in the Jewish community. “Politics was his sole occupation now,” says Segev, whose book draws on new archival material.

He also played a key role in the formation of the Palestinian Workers’ Party, or Mapai, the forerunner of the Labor Party. Later, he became the chairman of the Jewish Agency, probably the most important institution in the Yishuv.

From the outset, Ben-Gurion was a pessimist insofar as the possibility of Jewish-Arab amity was concerned. “There is no solution to that question,” he said in a reference to the dispute between Jews and Arabs. At best, the conflict could only be managed, he said.

Ben-Gurion’s relations with Chaim Weizmann, the elder statesman of Zionism, were testy. Unlike Weizmann, he believed that a Jewish state rather than a Jewish homeland should be created. In the early 1930s, Ben-Gurion was certain it should be established on both sides of the Jordan River, a maximalist position he would moderate.

After the rise of Nazism in Germany, Ben-Gurion warned that the Zionist project would flounder if Palestine’s Jewish population was not doubled. He defended the controversial Haavara agreement between the Nazi regime and the Zionist movement as a rescue operation. Under the accord, German Jews could settle in Palestine if they brought German-manufactured goods with them, thereby breaking the economic boycott against Germany.

Supporting the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, he justified his stance on the grounds that “a partial Jewish state is not the end but the beginning.” As he put it, “Our right to Palestine, all of it, is unassailable and eternal … I will not concede a single inch of our soil.”

In reality, he was a pragmatist. He adopted a dual approach to Britain’s 1939 White Paper, which drastically emasculated the prospects of Jewish statehood. With World War II raging, he proposed bringing one million European Jews to Palestine, an idea that never materialized. Only 50,000 to 60,000 Jews reached Palestine, 16,000 of whom were smuggled in illegally.

Segev discloses that Ben-Gurion tried to save hundreds of thousands of Jews in Romania, Slovakia and Hungary in exchange for bribes. All three attempts failed. He opposed Allied air raids to bomb the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, fearing that Jewish inmates would be killed. But the Allies were never seriously interested in bombing that killing factory.

For Ben-Gurion, the Holocaust boiled down to a defeat for Zionism. As he said forlornly, “Where will we get people for Palestine?”

After the war, he sent emissaries to Europe to bring Jewish refugees to Palestine, regarding them as a “Zionist fighting force.”

For a brief moment in time, he cooperated with the British authorities to hunt down members of the far-right Etzel and Lehi militias. During the “saison,” one of the most controversial periods in Zionist history, about 300 of their operatives were arrested.

He had advance warning of the Irgun’s plan in 1946 to blow up the King David Hotel, the headquarters of the British Mandate, but opposed it.

According to Segev, he wanted the Mandate to continue because the Haganah, the main Jewish fighting force, was not prepared for a war with the Arabs. On the other hand, he adds, Ben-Gurion insisted on declaring statehood immediately after the departure of the British from Palestine.

Yigal Allon, an army commander during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, tried without success to convince him that Israel should conquer the West Bank and draw its eastern border at the Jordan River.

Ben-Gurion had no qualms that upwards of 750,000 Palestinian Arabs fled, or were forced to leave, during the war. He hoped they would be successfully absorbed by neighboring Arab countries. On occasion, he broached the idea of allowing the refugees to return, but these were “diplomatic gestures” aimed at enhancing Israel’s international image, says Segev.

The major achievements of the war were two-fold. Israel captured 40 percent more territory that the United Nations had assigned to a Jewish state under the 1947 partition plan. And the Arabs who remained in Israel were a tiny minority, forced to live under military rule, their movements restricted, until 1966.

Israel paid a heavy price for its victory — close to 6,000 Israeli dead, including 2,000 civilians, and 12,000 wounded. But the outcome of the war bolstered Bon-Gurion’s political standing, and he reached the pinnacle of his career in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

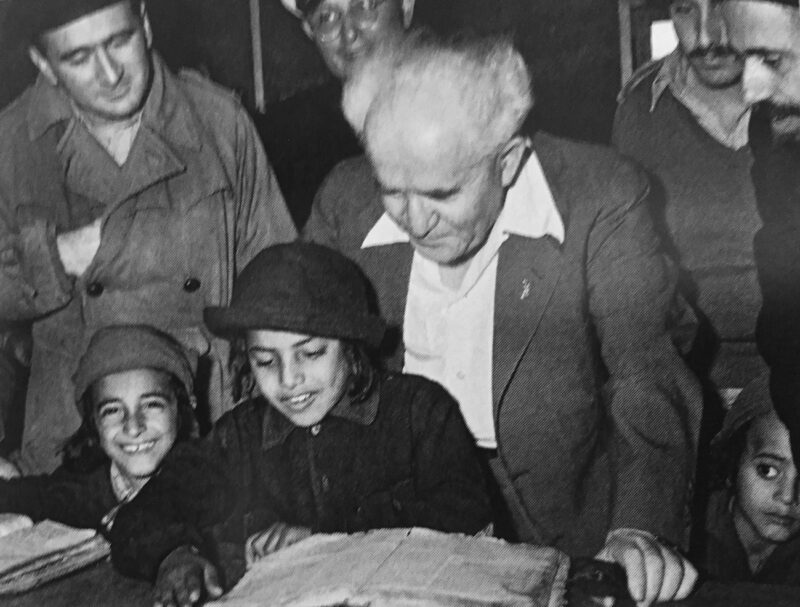

Yet the post-war era was exceedingly difficult. New immigrants had to be absorbed quickly, and a new wave of Arab terrorism inundated the country. But the institutions that had been built prior to statehood functioned smoothly. During its first 15 years of existence, Israel grew stronger, and under Ben-Gurion’s leadership the foundations for further progress were laid.

Israel, under his watch, turned away from a policy of non-alignment and joined the Western camp. Ben-Gurion was not hesitant to forge friendly relations with West Germany, whose reparation payments enabled Israel to recover from austerity and improve its economy. He cultivated a relationship with West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer that proved to be beneficial to Israel.

No longer able to tolerate the “mental pressure” of his job, he took a leave of absence. He and his wife, Paula, settled down in Sde Boker, a kibbutz in the Negev desert. “On his first day of work, he cleaned manure out of the stable,” says Segev.

Several years later, he returned to politics as minister of defence in Moshe Sharett’s government. Their differences over Israeli reprisal raids into neighboring Arab countries were a source of tension between these rivals.

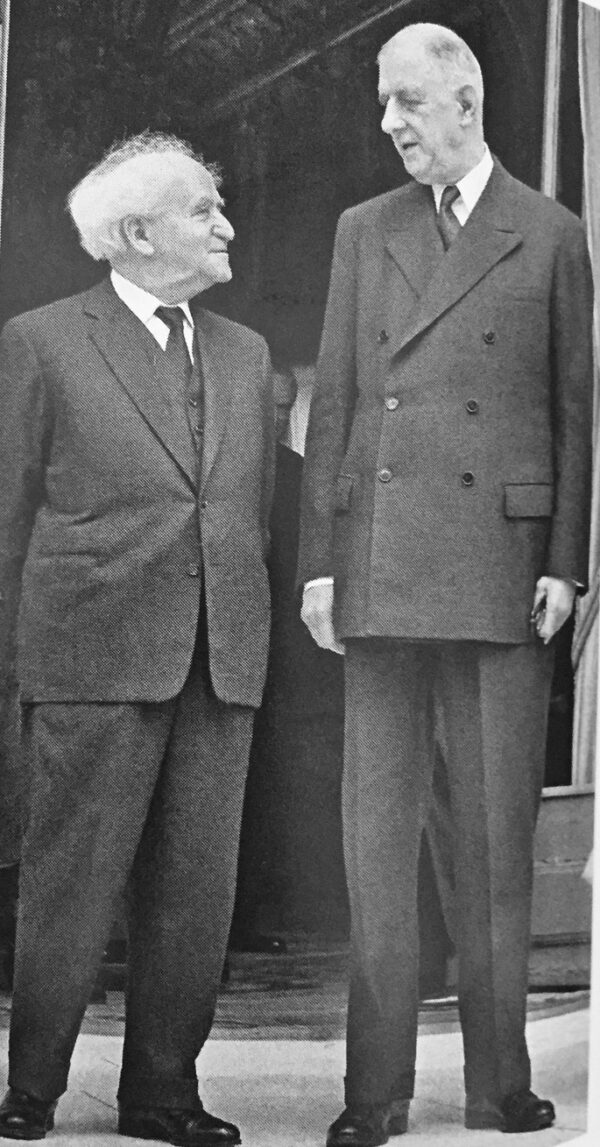

Segev argues that the chief of staff of the armed forces, Moshe Dayan, and the director-general of the Ministry of Defence, Shimon Peres, convinced Ben-Gurion that Israel should throw in its lot with Britain and France to invade Egypt in 1956. After the Sinai war, Israel formed close ties with France. In 1960, Ben-Gurion met the French president, Charles de Gaulle, in Paris.

Fearing that Israel could be destroyed by its enemies, Ben-Gurion believed that it required a nuclear capability. With the assistance of France, Israel built a reactor in Dimona, hoping that its Arab foes would abandon their dreams of obliterating the Jewish state. As he said, “We need deterrence, not victory in war.”

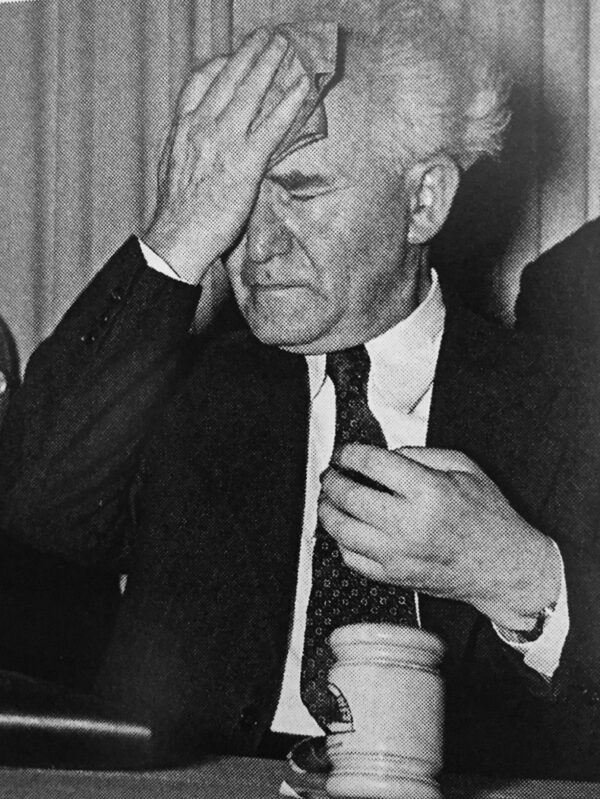

In the early 1960s, Ben-Gurion began to show signs of cognitive decline. He resigned in 1963, explaining that he lacked the fortitude to bear responsibility for his decisions. He had nothing but disdain for his successor, Levi Eshkol, who, he thought, did not possesses the “moral and national qualities” of a prime minister.

Reluctant to leave politics altogether, he formed a new party, the Israel Workers List (Rafi), but it won only 10 Knesset seats and was never a real factor on the political scene. As a result, Ben-Gurion found himself in the opposition for the first time.

Contrary to the view of the general staff, he opposed a preemptive strike on Egypt and Syria in the days leading up to the 1967 Six Day War. He feared that a war would require Israel to conquer the West Bank, with all its Palestinian Arab inhabitants, and create an unsurmountable demographic problem. Nor did he think that Israel should capture the Sinai Peninsula or the Golan Heights.

When he informed the chief of staff, Yitzhak Rabin, that Israel had erred in calling up the reserves, Rabin panicked and suffered a nervous breakdown that kept him out of commission for a few days.

Following Israel’s victory, he issued a statement recommending an Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai as part of a peace treaty with Egypt, but he felt that Israel should keep the Golan, even if Syria was willing to sign a peace treaty. He believed that Israel should control Gaza and East Jerusalem and maintain a military presence along the western bank of the Jordan River. As for the Palestinians of the West Bank, they should be granted autonomy and access to the port of Haifa.

“If I had to choose between a small Israel with peace and a large Israel without peace, I would prefer a small Israel,” he said, adding that Israel’s survival ultimately depended on enticing millions of Diaspora Jews to make aliyah.

Although Ben-Gurion sought to create a “new Jew” in Israel, he remained essentially a Polish Jew until the end, with his feet firmly planted in the Eastern European milieu from which he had come.

From a personal perspective, he never changed. He was an egocentric, deceptive, vindictive and humorless person, as far as Segev is concerned. And although he was attached to his wife and children, he plunged into affairs, driven solely by “animal urges,” as one of his lovers indicated.

Ben-Gurion died on December 1, 1973, about a month and a half after the Yom Kippur War, which exacted a horrible toll on Israel. “During his final days, his mind was foggy,” wrote one of his last visitors, Moshe Dayan. “He was unable to speak, his eyes were closed, and his mouth pursed. He left the world calmly, his life slowly ebbing away.”

As his doctor recalled, he was an old and weary lion, secure in the knowledge that his place in the annals of Zionism was assured.