Fifteen years after its unilateral withdrawal from southern Lebanon, this combustible area remains a thorn in Israel’s side and a potential threat to regional peace.

Since completing its hasty pullout on May 24, 2000, Israel has fought a war with Hezbollah — the Lebanese Shiite movement aligned with Iran and Syria — and may yet fight another one.

Prior to the Six Day War, Israel’s border with Lebanon was the quietest one in the Arab-Israeli arena. While Israel was at odds with Egypt, Syria and Jordan, the Israel-Lebanon frontier was consistently tranquil. It was said in optimistic tones that Lebanon would be the first Arab country to sign a peace treaty with Israel.

The Lebanese bubble burst in the wake of the Six Day War as the Palestine Liberation Organization, headed by Yasser Arafat, extended its control over southern Lebanon and used it as a launching pad from which to attack northern Israel.

The weak and divided Lebanese government was powerless to stop Palestinian guerrilla raids, particularly after Lebanon slid into civil war in 1975. In a bid to eradicate Palestinian bases and encourage the Lebanese government to crack down on the PLO, Israel launched reprisal raids by land, sea and air. Southern Lebanon became one of the hottest flashpoints in the Middle East.

Israel also invaded Lebanon, first in March 1978 and then in June 1982.

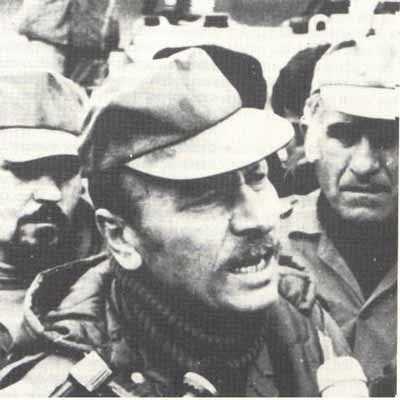

Around this time, Israel created a self-declared security zone in southern Lebanon and subsidized the formation of the South Lebanon Army, an anti-PLO Lebanese militia led by Saad Haddad, a former officer in the Lebanese army. Israel’s occupation was fiercely resisted by Hezbollah, which exacted a bloody toll on Israeli troops.

Israel sought to withdraw from Lebanon within the framework of a peace agreement with Syria, but when that option fizzled, the then Israeli prime minister, Ehud Barak, decided that Israel had no alternative but to carry out a unilateral withdrawal, which was completed within two days in May 2000.

With Israeli troops no longer in southern Lebanon, Hezbollah, based in Beirut, established a strong military presence south of the Litani River. Like the PLO of the late 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, Hezbollah — a major force in Lebanese politics — created a de facto state-within-a-state in the rugged border terrain adjacent to Israel.

The Lebanese army and the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon, which had been formed after Israel’s 1978 invasion, were supposed to maintain security in southern Lebanon. But in actual fact, Hezbollah took charge.

Almost immediately after Israel’s withdrawal, Hezbollah periodically initiated hostilities, kidnapping and killing three soldiers in October 2000, laying mines and firing occasional missiles after that.

A border incident in July 2006, during which several Israeli troops were killed after two soldiers were kidnapped in a Hezbollah ambush, escalated far beyond Hezbollah’s calculations. Calling it an act of war, Ehud Olmert, the then Israeli prime minister, ordered massive reprisals. Hezbollah responded, firing scores of missiles at Israel.

The Second Lebanon War claimed the lives of more than 1,000 Lebanese and 164 Israelis, primarily soldiers, before it ended in August in a draw. By the end of the war, Hezbollah had fired some 4,000 missiles toward Israel, displacing Israelis and disrupting Israel’s economy.

Through this war, Israel restored a measure of deterrence — killing hundreds of Hezbollah fighters, destroying thousands of its missiles, wreaking destruction on Shiite towns and villages and reducing to rubble parts of Dahiya, a Shiite neighborhood in Beirut where Hezbollah maintained its headquarters.

Shortly after the war, Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s spiritual leader, admitted he was surprised by Israel’s disproportionate reaction and suggested he would have acted with restraint had he known better.

Nine years on, southern Lebanon remains a tinderbox, though Hezbollah is not disposed to wage war at this moment.

Hezbollah, with 100,000 missiles and rockets at its disposal, is far stronger today than it was in 2006. According to recent media accounts, Hezbollah’s military infrastructure is now more deeply embedded in southern Shiite villages than was the case in the last war.

Hezbollah has built rocket-launching sites, anti-tank and infantry positions, underground tunnels and arms depots in these places. Hezbollah cynically regards Lebanese villagers as human shields.

Like Hamas in the Gaza Strip, Hezbollah is recklessly endangering Lebanese civilians. Should another war break out in southern Lebanon, Israel would not hesitate to bomb these villages, notwithstanding the inevitable political and humanitarian fallout.

Tensions between Israel and Hezbollah have been rising since January, when an Israeli air strike killed six Hezbollah fighters and an Iranian general on the Syrian side of the Golan Heights. Hezbollah, in coordination with Iran, has set up bases there.

By way of retaliation, Hezbollah killed two Israeli soldiers on patrol in the Shebaa Farms district, which Israel captured from Syria in the Six Day War but which Lebanon claims as sovereign territory.

Two months ago, the United Nations Security Council voiced “deep concern” over these incidents.

Israel’s front line with Hezbollah has been quiet for the past few months, but shooting could break again, despite Hezbollah’s increasingly growing military involvement in Syria’s civil war on the side of Syrian President Bahar al-Assad.

Hezbollah has lost hundreds of its best trained soldiers in these battles, but many more have honed their skills under fire. It goes without saying that Israeli soldiers will confront battle-hardened Hezbollah fighters in the next round of fighting in southern Lebanon.