They were idealistic left-wing Jews whose overarching objective was to build a “shenere un besere velt,” a more beautiful, better world.

Secular in orientation, steeped in socialism, dedicated to the Yiddish language, committed to the Soviet Union as their ideological fatherland and determined to improve the lot of the Jewish working class, they were members of a unique subculture with roots in Eastern Europe and branches in countries ranging from Canada, the United States and Britain to South Africa, Argentina and France.

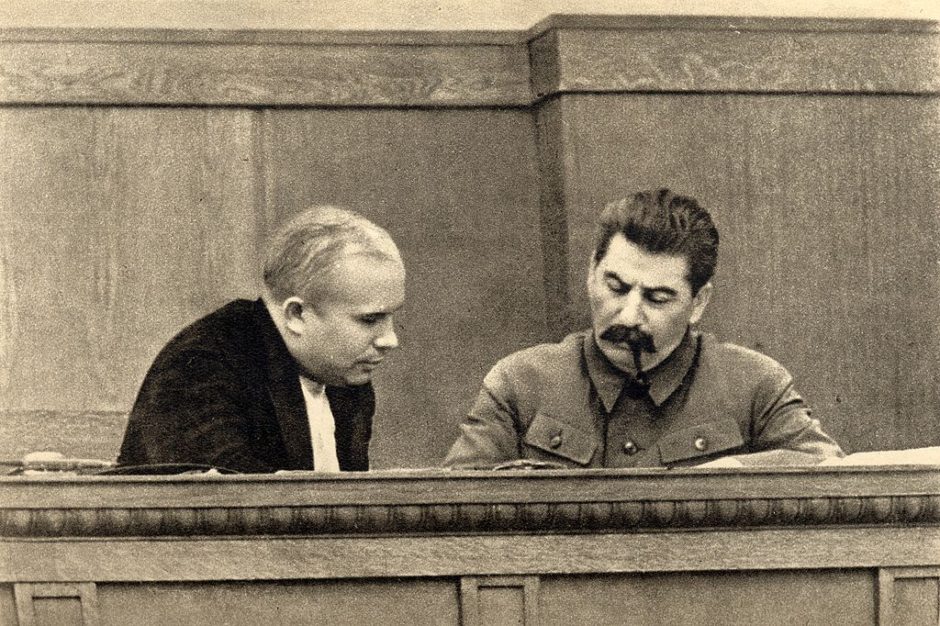

Active from about 1917 to 1956, a nearly 40-year period bookmarked by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s shocking revelations about Joseph Stalin’s crimes and antisemitic campaigns, they belonged to what Mathew B Hoffman and Henry F. Srebrnik describe as “the Jewish Communist movement.”

Blending Marxist universalism with Jewish nationalism, and infused with the philosophy of Labor Zionism and the Jewish Labor Bund, this world-wide movement reached its apogee of influence between the mid-1930s and the late 1940s.

Battered by disillusionment with the policies of the Soviet Union and by inexorable socio-economic changes, the movement plunged into a steep decline and all but disappeared. Today, it’s little more than a historical memory.

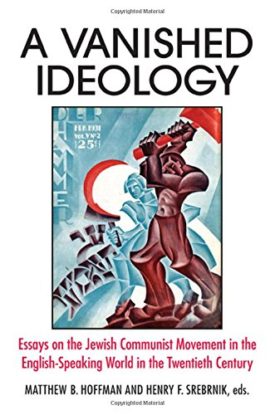

In A Vanished Ideology: Essays on the Jewish Communist Movement in the English-Speaking World in the Twentieth Century (State University of New York Press), Hoffman, Srebrnik and accompanying essayists examine this phenomenon in rigorous fashion. Journalists and scholars have delved into it over the years, but this appears to be the first academic treatment of the subject.

The introductory essay, written by the authors, provides readers with an excellent panoramic overview of their intriguing topic. Srebrnik, a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island, and Hoffman, an associate professor of Judaic Studies and history at Franklin and Marshall College, know the subject like the back of their hands. They’ve mastered the material and convey it in clear, fluid and accessible prose.

Their book should be required reading for anyone interested in understanding the nuances of the nexus between Jews and Communism in the 20th century.

Jews who gravitated toward this movement were animated by a desire to combat antisemitism and establish a just society. The Soviet Union, a nation that tore down class barriers, championed the rights of workers and declared antisemitism a crime, was their spiritual homeland and model state.

Unlike assimilated Jewish-born Communists, like Leon Trotsky, who distanced themselves from their Jewish past and who would not have shed a tear had Jews vanished from the planet, they saw a collective and distinctive future for Jews. “Rejecting religious and traditional Judaism, the Jewish Communists believed they could advance their cultural self-identity within a Marxist-Leninist framework,” Hoffman and Srebrnik write.

With his in mind, they formed their own immigrant organizations — the United Jewish People’s Order in Canada and the Jewish People’s Fraternal Order in the United States — schools, summer camps, newspapers, journals and publishing houses.

“But the Jewish Communist movements were not simple extensions of Communist parties,” Hoffman and Srebrnik add in an important caveat. “A majority of their members were neither Communist Party members, nor even Communists.”

That being the case, the movement was riven by a contradiction that was never really resolved. “It was Jewish, its focus was on Jews and the Jewish world, yet it tied itself to a non-Jewish ideology.”

The Birobidzhan project, one of the defining features of the movement, proved to be a failure as well. A sparsely-populated region of 36,900 square kilometers near Manchuria, it was set aside in 1928 by Moscow for Jewish settlement. Elevated to the status of a Jewish Autonomous Region in 1934, it was seen as a Soviet Zion where a proletarian Jewish culture could thrive. But Birobidzhan, with a limited Jewish population, never achieved its potential and became a source of disappointment.

Jews associated with the movement posted significant electoral victories from the 1940s onwards. Fred Rose of Montreal and J.B. Salsberg of Toronto won national and provincial parliamentary seats in 1943 and 1945, Phil Piratin of London swept into the British parliament in 1945.

“Jewish Communism remained a significant force until the mid-1950s, when its demise was swift and far-reaching,” write Hoffman and Srebrnik.

The Soviet Union, with Stalin at its helm, crushed nearly all aspects of institutional Jewish life, arresting Jewish personalities, closing Jewish schools and newspapers and circulating antisemitic tracts. Khruschchev, in a stunning speech to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party in 1956, revealed the betrayal in all its bitter details.

Birobidzhan, meanwhile, was exposed as an utter hoax, and Moscow’s decision to align itself with the Arab world against Israel was yet another disappointment.

“By the mid-1950s, the vast majority of Jewish Communists, forced to choose between their Jewish and their pro-Soviet attachment to socialism, overwhelmingly chose the former,” say Hoffman and Srebrnik.

More was yet to come.

The Soviet Union’s uncritical support of the Arab side in the Six Day War, plus the anti-Zionist campaign in Poland from 1967 onward, were bitter blows.

As Jews migrated from downtown neighborhoods into the suburbs, and as they left the garment industry and turned to business and the professions, the dream of a Jewish subculture informed by Communist values went by the boards.

The large influx of Holocaust survivors to North America and Australia had an effect, too. These newcomers tended to be more traditional in outlook and had few illusions about Communism or the Soviet Union. The latest batch of Soviet immigrants, who streamed out of the Soviet Union from the late 1980s onward, reinforced perceptions that the Bolshevik experiment had fizzled.

“All these changes shifted the community away from the far-left politically,” Hoffman and Srebrnik observe succinctly.

In his survey on the movement in the United States, Hoffman points out that Jewish intellectuals, writers, labor leaders and workers played a pivotal role in the growth and development of the Communist Party. Yet from the outset, some Jews in the party, particularly those who retained strong links to their Jewish background, had “to navigate between embracing Communist internationalism … and Jewish particularism.”

A man like Moyshe Olgin, the long-time editor of the Yiddish Communist daily, Morgn-Frayhayt, was a typical example of this dichotomy. Although he served on the Central Committee, he never became a power in the party due to his intense attachments to Jewish affairs.

The dividing line between Communists and non-Communists solidified in the wake of the 1929 Arab riots in Hebron, during which scores of Jews were killed. Initially, the Morgn-Frayhayt described the riots as a pogrom. But after the newspaper was rebuked by the Communist Party for engaging in “crass right-wing deviation,” it changed course and blamed the “Zionist-Fascists” for provoking it.

In another essay, Gennady Estraikh dwells on Olgin’s successor, Paul Novick, a standard-bearer of Yiddish Communism who remained in his post until the closure of Morgn-Frayhayt in 1988. Born in the then-Russian city of Brest-Litovsk in 1891, he arrived in the United States in 1913. A garment worker at first, he moved into journalism in 1915.

Novick’s transformation into a critic of Soviet policy was precipitated by Khruschchev’s seminal speech, the appearance in 1963 of Trofim Kichko’s antisemitic Ukrainian tract, Judaism Without Embellishment, and the antisemitic campaign in Poland in the wake of the Six Day War.

Jettisoning the Soviet line of condemning Israel as an aggressor and of hailing Arab states as bastions of anti-imperialism, Novick proclaimed his allegiance to Israel and aligned himself with Israeli Communist leaders critical of Moscow’s pro-Arab position.

Predictably enough, Novick was expelled from the Communist Party, charged with “opportunistic capitulation to the pressures of Jewish nationalism and Zionism.” He, in turn, accused the party of hatred for Israel bordering on antisemitism and “talked himself into believing that he was a custodian of real Leninism, whose ideas had been distorted by Soviet, American and other Stalinist-style pseudo Communists.”

Srebrnik, in Chasing an Illusion, analyzes the Jewish Communist movement in Canada.

In the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution, many Jews in Canada supported the Soviet Union uncritically. Jewish Communists, in particular, claimed that Communism was “the only true and sensible solution” to the “national question.” Among them was Joshua Gershman, who would be editor of Der Kamf from its founding in 1924 to its last edition in 1978.

Throughout the 1930s, he notes, Jewish Communists regarded Zionism as their chief enemy, going as far as to accuse the Histadrut labor union in Palestine of collaborating with Adolf Hitler’s regime by selling oranges to Nazi Germany.

Srebrnik reminds a reader that the Association for Jewish Colonization in the Soviet Union, known as ICOR, was not admitted into the Canadian Jewish Congress. Later, Congress expelled the United Jewish People’s Order from its ranks.

By one account, 30 percent of the Communist Party’s membership in Toronto in the 1940s was Jewish. In Quebec, the figure may have been as high as 70 percent.

Given these numbers, Jewish politicians associated with the party fared relatively well in elections. One of them, Fred Rose, who would be convicted of espionage, delivered a pro-Zionist speech in the House of Commons in which he expressed the hope that “Arab leaders will understand that the mass migration of Jewish people into Palestine is essential …”

The Soviet Union was the first country to recognize Israel, but Moscow eventually turned its back on the Jewish state, prompting the defection of Jews from the Communist Party. J.B. Salsberg, the Toronto alderman and member of the Ontario parliament, left the party in 1957 and was roundly denounced by its leader, Tim Buck, as a renegade who had dared question Soviet policies.

Ester Reiter, in The Canadian Jewish Left, says that the antisemitism Jewish immigrants encountered in Canada served “to strengthen the radical beliefs they had forged in eastern Europe.”

Writing about Quebec’s 1937 Padlock law, an offensive piece of legislation which enabled 21 Montreal police officers to raid the Morris Winchevsky Cultural Center, Reiter uses this shameful 1950 incident to expose the timidity of the now-defunct Canadian Jewish Congress.

Congress decided that the raid was not a Jewish issue, widening the gap between the mainstream Jewish community and the Jewish Communist movement. Another source of discord was the Korean War. Congress’ leadership supported it, but the United Jewish People’s Order came out against it, resulting in its expulsion from Congress.

Stephen Cullen’s essay, Jews in the Communist Party in Great Britain, suggests that the party exploited the Jewish fear of fascism and antisemitism for its own political ends. When Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists began expanding into London’s East End, where many Jews lived, Communist organizers set out to create “Little Moscows,” not only in London but in Manchester, Leeds and Glasgow as well.

The party was also appealing to Jews due to its aggressive stance on unemployment, underemployment and poor housing conditions.

Cullen says that Labour Party strategy in Stepney — a London neighborhood with a high concentration of working-class Jews — hinged on winning the loyalty of ethnic Irish voters, who had a deep aversion to Communism. As a result, he notes, the party resisted being drawn into the anti-fascist struggle, both at home and abroad.

Philip Mendes’ essay, Jewish Communism in Australia, comes to the point quickly. It was a “relatively minor affair” down under. Nonetheless, for a brief time between 1942-1950, it attained “a significant presence in the Jewish community.”

Jews were drawn to the Communist Party by a number of factors, foremost among which was its strong opposition to antisemitism and its commitment to equality for Jews. But the party’s defence of the Slansky trial in Czechoslovakia and the Doctors’ Plot in the Soviet Union eroded remaining Jewish support for Communism.

Two of the founding bodies of the Communist Party in South Africa were the Jewish Socialist Society in Cape Town and Johannesburg, says David Yoram Saks in his essay.

“Whereas in Western democratic societies, Communism has been largely a fringe phenomenon, Communists (in South Africa) actually succeeded in achieving political power with the overthrow of the white minority apartheid system and the ushering in of multiracial democracy,” he observes.

Two of the leading figures in the South African Communist Party were Joe Slovo and Solly Sachs, who were rewarded with cabinet posts after the advent of black majority rule. No less a person than Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first black president, wrote in his autobiography that Jews were “more broad-minded than most whites on issues of race and politics, perhaps because they themselves have historically been victims of prejudice.”

Most South African Jews did not support the agenda of Jewish Communists, but neither did they endorse the segregationist race policies of the ruling National Party. To this day, he says, the rift between mainstream Jews and left-wing Jewish activists has yet to to be bridged

In closing, Hoffman and Srebrnik write that the Jewish Communist movement was ultimately unable to survive “the twists and turns of Soviet policy toward the Jews.”

In the Soviet Union, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was disbanded shortly after the war, and not a single Yiddish publication appeared from 1948 until 1959. The last Jewish schools were shuttered, and Jews were eased out of political, diplomatic and military positions.

“The negative Soviet attitude toward its Jewish population would become more apparent when (it) began to provide ideological, military and economic support to Israel’s Arab neighbors,” they note

And as they go on to say, the underpinnings of the movement unravelled with increasing assimilation and the gradual disappearance of Yiddish as a marker of Jewish ethnic identity.