Thanks to his diaries, published in two volumes by Indiana University Press in 2007 and 2009, James Grover McDonald has received the recognition he so richly deserves.

McDonald (1886-1964), an American who worked tirelessly in the 1930s and 1940s to find a safe haven for Jews fleeing Nazi Germany, was the first U.S. ambassador to Israel. All this might have been forgotten had a researcher not stumbled upon his diaries in 2003.

Shuli Eshel’s poignant documentary, A Voice Among the Silent: The Legacy of James G. McDonald, which was broadcast on the PBS network on November 12, delivers McDonald’s story to a wider audience.

Hard-wired for decency, McDonald was a humanitarian in an era when rampant racism and casual antisemitism were discouragingly endemic. He understood the menace of Nazism as few of his contemporaries did and he spoke his mind about it. Morally courageous and sympathetic to the underdog, he was a man ahead of his times. Eshel’s documentary traces his life from his birthplace in Ohio to his role as an advocate for Jewish refugees and a champion of Israeli statehood.

After a stint as a University of Indiana professor, McDonald was appointed chairman of the Foreign Policy Association. In this capacity, he visited Germany two months after Adolf Hitler’s ascension to power. McDonald — whose mother was an ethnic German — witnessed the Nazi boycott of Jewish shops at first hand.

Having been granted a meeting with Hitler, he raised the Jewish question. At first, Hitler claimed the issue had been overblown, but then launched into a diatribe against Jews, saying they had to be eliminated from German society. McDonald’s unpleasant encounter with Hitler convinced him that Jews had no future in Germany and needed saving. This is what he told President Franklin Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, whom he had befriended.

Fluent in German, McDonald lobbied Roosevelt for the ambassadorship to Germany, but he was denied the post. As an apparent consolation prize, he was appointed high commissioner for refugees at the League of Nations, to which the United States did not belong. He resigned after concluding that the Roosevelt administration was not supportive of his work.

In 1936, McDonald joined the editorial board of The New York Times, only to step down two years later after realizing that the publisher disagreed with many of his views.

As a member of Roosevelt’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees, McDonald was a U.S. delegate to the ill-fated 1938 Evian conference, which turned out to be a bust. He was also disillusioned by the president’s abject failure to honor a promise to allot $150 million to resettle German-Jewish refugees.

Much to his further disappointment, the U.S. State Department kept cutting the refugee quota after 1940, when the plight of Jews in Nazi-occupied countries worsened. His nemesis was Roosevelt’s buddy, Breckinridge Long, the bigoted assistant secretary of state for refugees.

Amid the gloom, McDonald salvaged some victories. He collaborated with Varian Fry, an American journalist based in France, in rescuing some 2,000 Jews. And he played a behind-the-scenes role in persuading Roosevelt to establish the War Refugee Board, which saved more than 100,000 imperilled European Jews, particularly in Hungary.

Roosevelt’s successor, Harry Truman, appointed McDonald to serve on the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine, whose mandate was to ascertain whether Holocaust survivors stranded in Europe should be allowed to settle in Palestine. He had no doubts about it. “The gates of Palestine must be opened,” McDonald declared.

Believing that Palestine could be a refuge for at least some of the survivors, he endorsed the United Nations Palestine partition plan, passed on November 29, 1947 by a margin of 33-13.

In June 1948, a month after Arab armies invaded Palestine in an attempt to crush the newly-proclaimed Jewish state of Israel, McDonald got a telephone call from Clark Clifford, one of Truman’s pro-Zionist aides. Would he accept a position as the U.S. special representative in Israel? Secretary of State George Marshall opposed the appointment, but the Senate approved it.

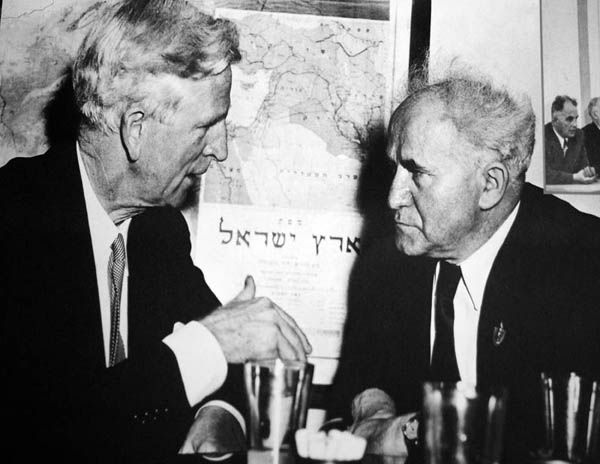

McDonald and his daughter arrived in Haifa in August 1948. Shortly afterward, he received word his job had been upgraded. He thus became America’s first envoy to Israel. He stayed until 1951, building from scratch a relationship that has endured through thick and thin. In the opinion of an Israeli academic who appears in the film, one of several who periodically pop up to offer comments, McDonald was the most committed and friendly American ambassador who ever served in Israel.

After leaving Israel, he wrote his memoirs, My Mission in Israel, and contributed his knowledge and expertise to the Development Corporation for Israel.

He was a sincere Zionist and a constant friend of the Jewish people, and Eshel’s film distills that spirit in fine fashion.