As improbable as it may sound, the Caribbean island of Jamaica was a wartime haven for European Jewish refugees fleeing fascism and antisemitism. Jamaica, then a British colony, began admitting imperilled Jews in 1938 and continued welcoming them through the early 1940s. This little-known footnote in the annals of the Holocaust could easily have fallen through the cracks of history. It does not due to Diana Cooper-Clark’s book, Dreams of Re-Creation in Jamaica, published by Friesen Press in Canada.

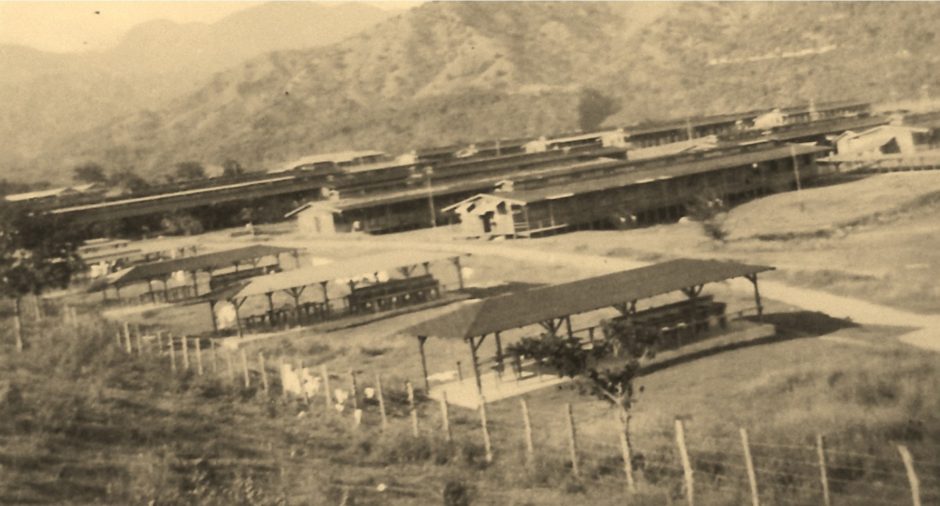

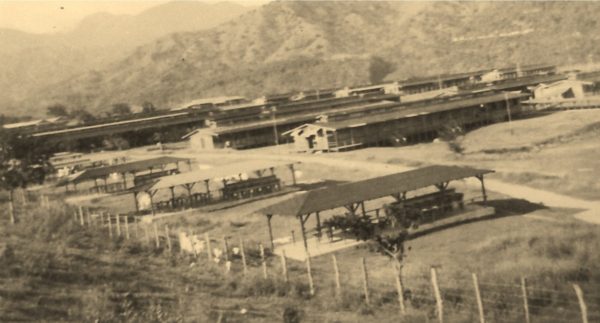

The refugees, mainly of Polish and Dutch ancestry, waited out World War II in the Gibraltar and Up Park internment camps in Kingston, the capital of Jamaica. Cooper-Clark, a professor in the departments of English and Humanities at York University in Toronto, describes their experiences through the prism of “hope, disappointment, pain, loss” and the prospect of a new life.

The author, whose interest in the Holocaust was sparked by a book she read at the age of six about the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, believes that about 1,400 Jews found refugee in these makeshift camps. They left Jamaica after the war, rebuilding their lives in countries such as the United States, Canada, Holland and Britain.

Cooper-Clark spices up her narrative with stories about refugees like Rudolph Aub, who was forced to leave his Christian wife and their children behind in Germany; Manfred Mann, who fled Leipzig after Kristallnacht and entered Belgium illegally before landing in Jamaica, and Yvonne Cardozo, who was born in Antwerp of Dutch parents.

Jamaica beckoned as a place of refuge after the British Foreign Office informed the Joint Distribution Board, a Jewish organization, that Jewish refugees could come to the island if it paid for their upkeep for at least a year and if the newcomers passed a security test ensuring they were not spies for the Axis powers.

She leaves the impression that many of the refugees were brought to Jamaica by Portuguese ships such as the Serpa Pinto and the SS Sao Thome. Upon arriving in Kingston, they were treated like enemy aliens, their passports stamped with the notation: “Permitted to land … but restricted to close supervision pending result of through investigation.”

Much to their disappointment, they were not permitted to look for jobs. And as time elapsed, some complained about conditions in the Gibraltar camp. One indignant refugee went as far as to liken Gibraltar to a Nazi concentration camp. “The comparison is an obscenity,” she writes, flatly dismissing the claim. “Gibraltar camp was a confined location for internees, but it certainly did not resemble the architectures of doom that were the Nazi concentration camps.”

Cooper-Clark adds that the refugees were fed reasonably well. They were no worse off than “the people of the island, and they were eating better than many impoverished Jamaicans.” She goes on to write: “People in Europe had not seen the kind of food served in the camp for years, such as meat, fruit, vegetables, butter and sugar. Ersatz coffee was all that Europeans had had for years, while … the refugees often had Blue Mountain coffee, one of the best in the world.”

Rejecting the allegation that the venerable Jamaican Jewish community was indifferent to the refugees, she contends that some local Jews were indeed helpful. Citing an example, she says that Owen Karl Henriques, a prominent businessman, worked tirelessly on their behalf.

In an interesting aside, she sketches a pen portrait of Jamaica’s long-established, highly assimilated Jewish community. Pointing out that mixed marriages have taken a drastic toll on its size since the 1880s, Cooper-Clark says the descendants of such unions are far removed from Judaism. She gives three examples. Chris Blackwell, a musician and recording executive who has worked with Bob Marley and the Rolling Stones, is related to the Jewish Lindo family. Harry Belafonte, the singer, has Jewish roots. Colin Powell, the former U.S. secretary of state, is descended from Jews on his father’s side.

In another aside, she informs a reader that 65 Jews from the Caribbean islands and Central America, almost all of them Sephardim, were murdered during the Holocaust. It’s a largely unknown fact, even to those familiar with the Holocaust.

Mexico tops this list with 23 victims, followed by Cuba (19), Curacao (15), Dominican Republic (two), Trinidad and Tobago (one), Saint Thomas, Virgin Islands (one), Guatemala (one), El Salvador (one), Nicaragua (one) and Guadeloupe (one). During this period, she says, the Nazis and their collaborators killed 160,000 Sephardic Jews.

Much to her credit, Cooper-Clark has rescued this obscure episode from oblivion. Although Dreams of Re-Creation in Jamaica is a workmanlike account well worth delving into, it’s disjointed and repetitious at times. These defects, though, are mere quibbles when compared to the broad sweep of her path-breaking book.