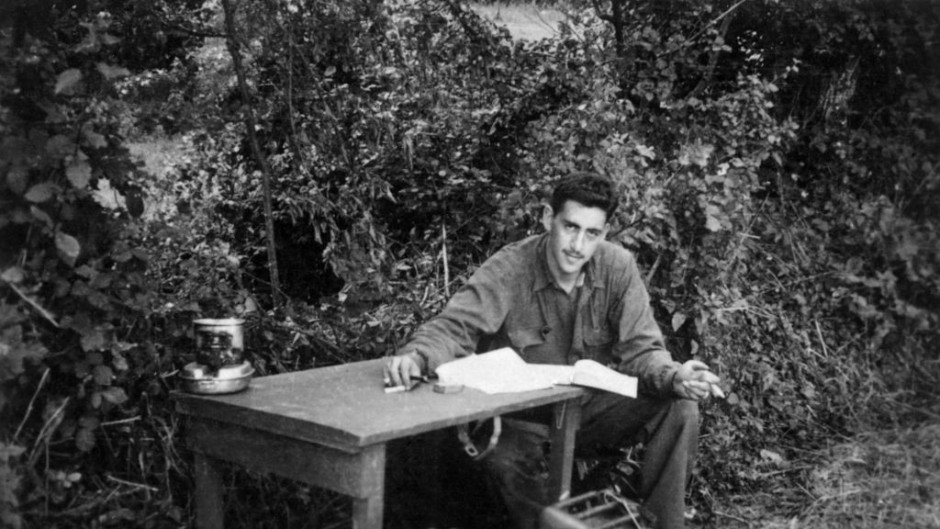

Jerome David Salinger, the great American novelist, was ubiquitous yet remote and elusive.

His iconic debut novel, The Catcher in the Rye, published in 1951, has been read by three generations of adolescents in the United States and the rest of the world and has sold an astonishing 60 million copies, a figure that staggers the imagination and will probably elicit enormous envy from fellow authors.

- J.D. Salinger

For all his fame and celebrity, Salinger, known as Jerry to his closed circle of friends and acquaintances, was a certified recluse. He never granted a formal interview. There are no video or audio recordings of him, as well as very few photographs. For much of his life, like a hermit, he lived in rural seclusion on the outskirts of a small town in New Hampshire, refusing contact with everyone but his family, old friends, neighbors and longtime associates.

He was the Howard Hughes of his day, as one observer has pointed out.

Salinger, the man and the writer, is the subject of Shane Salerno’s wonderful documentary, Salinger, which was recently broadcast on the PBS network’s American Masters series.

An official selection of the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival, Salinger is remarkable scope and substance. Salinger’s life, from youth to old age, is extensively explored, and cogent commentaries on his career and contributions are delivered by, among others, the novelists Tom Wolfe and E.L. Doctorow, the playwright John Guare and the biographer A. Scott Berg.

Salinger, they agree, was an extraordinary talent with a unique voice who was destined to be a published writer and who related to his fictional characters, from Holden Caulfield on down, as if they were living, breathing human beings.

By the same token, observers are still puzzled by his misanthropic retreat from the real world at the height of his powers and by his decision not to publish after the mid-1960s.

Salinger, who died in 2010 at the age of 91, hailed from a well-to-do New York City family. His father, a Jewish cheese importer, came from a long line of rabbis, and did not encourage his son’s literary ambitions. His mother, a Catholic, was his chief cheer leader. Unfortunately, they remain ciphers in this film. Nor does Salerno tell us how he related to the Jewish side of his heritage.

In the mid-1930s, Salinger was sent to the Valley Forge Military Academy, where he began writing. He published his first story, The Young Folks, in 1940.

From the outset, Salinger sought to be published in The New Yorker, which continually rejected his submissions. In the meantime, he succeeded in placing his stories in other national magazines. In 1941, The New Yorker finally accepted one of his short stories, but it was shelved due to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Exploring another facet of his development, Salerno examines Salinger’s romantic relationship with Eugene O’Neill’s beautiful and intelligent daughter, Oona, who ultimately spurned his advances and, at 18, married the 53-year-old Hollywood actor Charlie Chaplin.

Salinger enlisted in the armed forces in the spring of 1942 and was initiated into combat in June 1944, when Allied forces invaded Normandy in a bid to dislodge the German army in France. By then, he had already written six chapters of The Catcher in the Rye, a subversive and colloquial coming-of-age novel that took him a decade to finish.

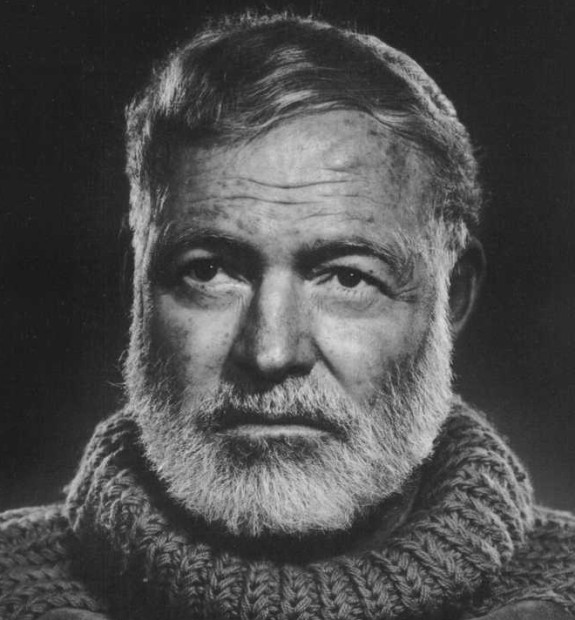

During the war, he served in the counter-intelligence corps, but continued publishing fiction in American magazines. He met his idol, Ernest Hemingway, in liberated Paris in 1944, and Hemingway liked the story Salinger had asked him to read.

Salerno suggests that Salinger’s experiences in U.S.-occupied Germany had a profound impact on him, but he doesn’t really elaborate. Salinger was one of the first American soldiers to venture into the Dachau concentration camp, where naked bodies were stacked up like logs. Appalled by Nazi crimes, he never got the smell of burning flesh out of his nostrils, and suffered a nervous breakdown.

Oddly enough, he married a German, Sylvia Welter, who may have been a Nazi party member. He introduced her to his family in New York, but their reaction is shrouded in mystery. Shortly afterward, Salinger divorced his first wife.

In 1946, bliss dawned when The New Yorker published his story, Slight Rebellion Off Madison. Salerno claims he achieved a literary breakthrough in 1948 with the publication of A Perfect Day for Bananafish in The New Yorker. From that point onward, he was inextricably identified with that magazine.

With The Catcher in the Rye, Salinger found his true voice, Salerno says. The first publishing house to which he submitted it asked for a rewrite. Self-confidently, he declined, shopping it around to another publisher. It was an immediate hit, resonating with a new generation of readers who appreciated its rebellious, anti-Establishment tone.

Instead of embracing adulation, he scorned it, finding peace and solitude in Cornish, New Hampshire, where the local people protected his privacy. Salinger worked in a bunker on his wooded mountain top property, turning out Nine Stories, Franny and Zooey and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction.

His obsessive work habits alienated his second wife, who filed for divorce. With her out of the picture, he cultivated relationships with a series of young women. Joyce Maynard, one of them, moved in with him and agreed to abide by his monastic regimen. Maynard, a vivacious and articulate person, claims he was “indulging in a fantasy of innocence” that could not last. The Maynard interview by far is one of the most interesting and revealing segments in Salinger.

Intriguing, too, are the recollections of two ardent fans who had awkward and disappointing personal encounters with Salinger.

According to Salerno, Salinger’s unpublished novels, short stories and novellas, some of which are rooted in World War II and the Holocaust, are scheduled to be published between 2015 and 2020.

One can only hope they are as good as the stories that have come before.