Joachim Fest’s thoughtful memoirs of his boyhood and youth, Not I (Other Press), transport a reader to a terrible time and a horrible place.

Born in Berlin into a conservative Catholic family, Fest was seven years old when Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. Fest’s father, Johannes, a German patriot and a supporter of the Weimar Republic, loathed the Nazis and refused to be coopted by the new regime. As a result, he was dismissed from his position as the headmaster of a primary school and effectively ostracized.

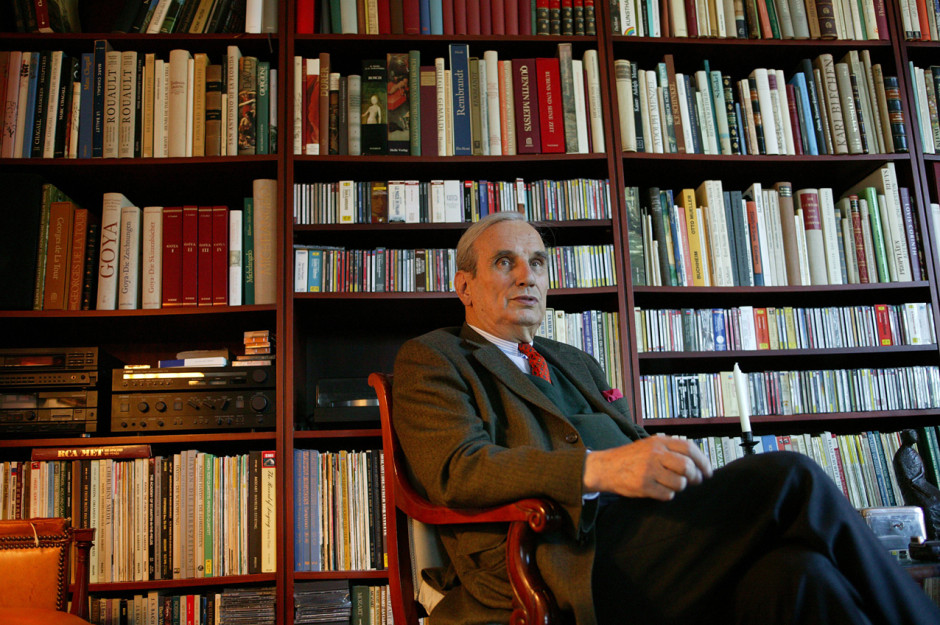

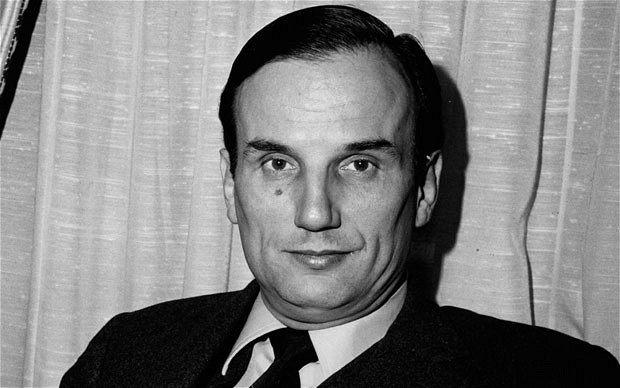

Fest, who would become a prominent historian and journalist in postwar western Germany, charts his father’s principled opposition to Nazism and his life after the Nazi interregnum. As well, Fest recalls his service in the German armed forces, his captivity as a prisoner of war and his career in West Germany.

Fest, the first German to publish a biography of Hitler, finished this memoir just before his death in 2006. It was a bestseller, and now Martin Chalmers has translated it into English. In all probability, North American readers will find Fest’s measured account of a society in transition and tumult quite interesting.

Johannes Fest, who’s at the center of this book, was “a rare combination of energy, self-confidence and mirth.” He was a member of the Zentrum Party and the Reichsbanner, a paramilitary organization set up in league with the Social Democratic Party and trade unions to defend the Weimar Republic from Nazi hooligans.

A realist, he did not share the view, then common in Germany, that Hitler would become more reasonable once he assumed power. And he was right. Shortly after Hitler assumed office, Johannes was summoned by his superiors and questioned on his attitude to the new government. Already considered a subversive, he did not bother concealing his animus toward the Nazis. His wife, worried by the obvious implications, was none too pleased by his obduracy.

On April 22, 1933, he was suspended from his job. Given a chance to recant, he refused, much to his wife’s displeasure.

Johannes’ reputation as a dissident in an increasingly totalitarian society had social consequences as well, Fest writes. “The previously friendly sales assistant in the grocer’s fell silent now as soon as my father came through the door. Acquaintances of many years disappeared into doorways or quickly crossed the road when he approached.”

He urged his vulnerable Jewish friends to leave Germany, but being loyal and patriotic Germans, they stayed put. “A nation, they said, that had produced Goethe, Schiller, Lessing, Bach and Mozart, and so many others, would simply be incapable of barbarism.”

In the face of rising antisemitism, Johannes implored them to emigrate, but they did not listen. “Everyone had mentioned countless reasons for staying, and he had even been accused of wanting, just like the Nazis, to make Germany Judenfrei — free of Jews.”

The outbreak of World War II, Fest observes, aroused a wave of loyalty to Hitler, but “a few seemed, for the first time, to have an inkling that the country had entered on a dangerous adventure.”

In 1941, two Hitler Youth officials accosted his father, demanding to know why his sons had not joined that Nazi organization. He stood his ground, ordering the pair out of his house.

Despite his sober assessment of the regime, Johannes was unable to grasp that Germany had embarked on a genocidal project to exterminate Jews in Europe. “It was true that he believed Hitler and his accomplices capable of anything. But in this case, he still believed it was one of those horror stories … the unscrupulous English propaganda had invented during the First World War.”

When Fest told his father he had volunteered for the German Air Force, he shouted in indignation. Fest explained that he had joined to avoid being drafted by the SS. “One does not volunteer for “Hitler’s criminal war,” he responded.

Captured at the battle of Remagen, Fest spent the rest of war as a prisoner in the custody of the American army. His parents survived the war, but his sisters came close to being gang raped by Russian soldiers. Upon being released, he was shocked by the devastation that Germany had brought upon itself.

After the war, Johannes joined the Christian Democratic Union Party, delivering speeches on the evils of Nazism. And in memory of some of his Jewish friends who had been murdered by the Nazis, he joined the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation.

As a young man, he says, he was fortunate enough to befriend one of his father’s Jewish friends who had made it through the war. To Fest, who would be the culture editor of the prestigious Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, he personified the contributions Jews had made to Germany prior to the Nazi era.

Fest takes issue with Jewish critics who contend that a German-Jewish symbiosis never existed. “This is very understandable as a response to injustice stretching over generations, and above all to the horrors of the Hitler years. But as a conclusion it remains inaccurate. The relationship between Jews and Germans was always deeper and more profound than, for example, that between Jews and the French or Jews and the English or the Scandinavians.”

Fest confesses that he struggled with “normalcy” in the wake of the war. “For anyone with eyes to see, the preceding years had swept away almost everything. To what should we cling?”

As he admits, he felt detached from conversations about the 1930s and 1940s in Germany. As he puts it, “We had the dubious advantage of remaining exactly who we had always been, and so of once again being the odd ones out.”

Indeed.