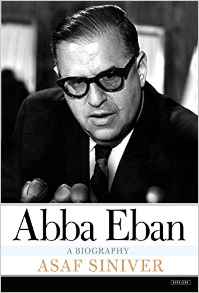

Abba Eban has been dead for 14 years but his name still resonates.

Eban was unquestionably Israel’s most eloquent foreign minister, defending the Jewish state at the United Nations and other international forums.

Hailed abroad as the Voice of Israel, he was regarded far less admirably at home. Although his contemporaries in Israel’s Labor Party acknowledged his skills as a brilliant public speaker, they disparaged his affected British mien and frowned upon his relatively moderate views on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

As Asaf Siniver observes in Abba Eban: A Biography (The Overlook Press), a magisterial work of scholarship, two of the most dominant figures in Israeli politics, Levi Eshkol and Golda Meir, adopted a strangely condescending attitude toward Eban.

Eshkol, his first boss, described him as “the wise fool.” Meir, Eshkol’s successor as prime minister, practically fell over herself in laughter when she heard he was considering running for the premiership following her resignation in 1974. “In which country?” she asked sarcastically.

As it happened, Eban dropped out of that leadership race. Yitzhak Rabin, fresh from his job as Israel’s ambassador to the United States, succeeded the lacklustre Meir as prime minister. Since Rabin disliked Eban with a passion, he relieved him of his post as foreign minister, replacing him with a demonstrably inferior candidate who was chosen on the basis of his political connections.

Having been frozen out of Israel’s inner circle, Eban continued to be a member of the Knesset. With his glory days behind him, he lectured at universities, spoke to Jewish groups, wrote widely admired books and served as the presenter of Heritage: Civilization and the Jews, one of the most critically acclaimed and commercially successful television documentary series ever broadcast.

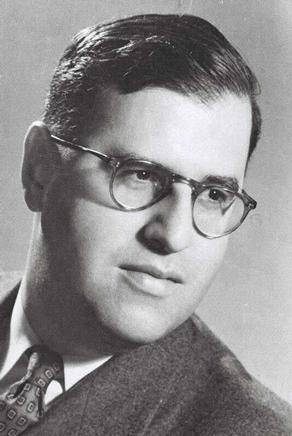

Aubrey Abba Eban, born in Cape Town and raised in London, was the son of non-observant Jews. Brought up in a secular and Zionist environment, he was editor of a Zionist youth magazine at the age of 16. An honours student at Cambridge, he studied classics and Middle Eastern languages. Although he seemed destined for a career in academia, he devoted himself to the Zionist movement after meeting three key Zionist figures.

During World War II, Eban was a junior officer in the British army, but in 1946 he joined the Information Department of the Jewish Agency in London. In his first diplomatic mission, he lobbied the governments of France, Holland and Belgium to support the 1947 United Nations Palestine partition plan, which was adopted by a considerable margin.

He was subsequently appointed Israel’s first ambassador to the United Nations and the United States, positions he held concurrently. In this capacity, he played a role in Israel’s decision to align itself with Washington rather than Moscow after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950.

Eban was privately critical of Israeli retaliatory raids into Jordan and Syria in 1953 and 1954, regarding them as excessive. But being a loyal servant of the state, he supported these incursions in speeches at the United Nations.

Like the rest of Israel’s diplomats abroad, Eban was left completely out of the loop by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion as he planned the 1956 invasion of Egypt in collusion with France and Britain. “For the rest of my life I shall never understand how it was possible to cause such frightening military commotion without a modicum of guidance to myself and other missions,” he would write in puzzlement and bitterness.

Nonetheless, Eban was an extremely able defender of Israel, fending off an implosion of Israel’s relations with the United States during this particularly tense period, says Siniver, a professor of international security in the department of political science at the University of Birmingham.

In Siniver’s judgment, Eban’s ambassadorial years were the “pinnacle” of his career “as one of the most eloquent and adroit diplomats of the century.”

Shortly after he and his wife returned to Israel in 1959, Eban was briefly president of the Weizmann Institute. But from the moment he set foot in the country, he was widely seen as something of an alien. Eban had shallow roots in the ruling Labor Party, and although he was fluent in 10 languages, he spoke neither Russian nor Yiddish, the languages of Israel’s pioneering elite. His proper English manners and his lavish American lifestyle were ridiculed. As for Eban, he was dismayed by what Siniver says was the “blatant anti-intellectualism that accompanied the criticism against him.”

Eban, nevertheless, was appointed minister-without-portfolio in Israel’s next government. It was, as Siniver points out, an “utterly useless” position for a person of his calibre. Eban’s subsequent appointment as minister of education and culture was more in keeping with his stature.

In 1966, he was appointed foreign minister, a role he cherished and excelled in for eight years. Oddly enough, his closest confidant in the ministry was his personal driver, Holocaust survivor Yacov Markovitch. Eshkol, the premier, admired Eban’s rhetorical skills, but was skeptical of his abilities as a strategist. “Eban never gives the right solution, only the right speech,” he said contemptuously.

For Eban, Israel’s acquisition of new territories in the 1967 Six Day War represented a golden opportunity to exchange land for peace with its Arab neighbors. In this spirit, he opposed the notion of annexing the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Yet Eban was not a dove. He did not believe that creating facts on the ground would predetermine Israel’s negotiation position, and he rejected the notion that there was a contradiction between Israel’s desire for peace and the building of settlements. Nor did he think the Israeli government should commit itself to a particular peace plan as long as Arab states spurned direct talks with Israel. At best, he was prepared to offer the Palestinians semi-independence status.

Under Golda Meir’s premiership, Eban’s position in the cabinet deteriorated. Meir, a hawk, did not appreciate his somewhat dovish outlook, and she detested his reluctance to fight for his views. Adding to Eban’s woes was Rabin’s intense antipathy to his style and demeanor. Like Meir, Rabin was disdainful of intellectuals.

During the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Eban was effectively a superfluous figure, having been sidelined by Meir. The catastrophic losses in men and materiel Israel sustained in that war forced Meir to resign. Eban backed Shimon Peres as Meir’s successor, but Rabin defeated him in a primary. Rabin offered Yigal Allon the foreign ministry, leaving Eban in the cold.

Humiliated by his ouster, Eban accepted a visiting professorship at Columbia University in New York City and an offer from Random House to publish his memoirs and a book on diplomacy.

Returning to Israel after Rabin’s ignominious resignation, he pledged to support Peres in his quest for the premiership. Peres promised to reinstate Eban as foreign minister, but the offer was rendered moot by the Likud Party’s victory in the 1977 general election. Although he retained his seat in the Knesset, Eban spent weeks and sometimes months in New York City, amassing a poor attendance record.

A fierce critic of Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, he branded it “the most miserable war in the country’s history.” The chairmanship of the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee provided him with a platform to enunciate his increasingly dovish views of how the seemingly intractable Arab-Israeli dispute could be resolved. By then, Eban was critical of Israel’s presence in the occupied territories and of its refusal to negotiate with the Palestine Liberation Organization.

In closing, Siniver concludes that “Eban’s story is ultimately one of failure.” Like his American friend Adlai Stevenson, Eban was the victim of anti-intellectualism. As long as he defended Israel during its hours of peril, he was a hero. “But once Eban arrived in Israel and entered the political arena, those qualities that had made him one of the most revered statesman of his generation now made him an easy target for ridicule and suspicion,” writes Siniver.

Eban, in his prime, was a shining symbol of Israel. But in the rough-and-tumble landscape of Israeli politics, he was tragically an outsider.