When I was a teenager, I would sometimes join my mother on her weekly shopping trips to Steinberg, her favorite supermarket in Montreal. She liked it because it was big, bright and bulging with an amazing variety of reasonably priced food and household goods.

If shoppers accumulated a sufficient number of Steinberg pink coupons, which looked like small postage stamps, they were eligible to receive, free of charge, leather-bound volumes from a popular American encyclopedia. After about eight months, we managed to collect the entire set.

By the late 1950s, Steinberg was the largest supermarket in the province of Quebec. Founded in 1917 by Hungarian Jewish immigrant Ida Steinberg as a simple retail grocery shop on St. Lawrence Boulevard, it outgrew its original premises and morphed into a formidable chain in the years leading up to World War II.

Steinberg’s son, Sam, and his brothers took over the burgeoning business after Ida’s death in 1942. By 1969, the Steinbergs owned 180 supermarkets, with 18,000 employees, in Quebec and Ontario. By then, the business had grown too large and unwieldy for Sam Steinberg to control, and he was ready to resign as president.

Sam Steinberg invited his top 15 managers to what would be a three-day meeting at the Palamino Lodge in the Laurentian mountains, north of Montreal, to discuss his pending resignation. Since he did not have a son who could succeed him, his successor would have to come from the ranks of his senior executives. It never occurred to him to designate one of his daughters as president. Such was the sexist climate of the day.

Arthur Hammond filmed the sedate proceedings, and his factual, fly-on-the-wall documentary, After Mr. Sam, was released by the National Film Board of Canada in 1974. It will be screened online in May during Canadian Jewish Heritage Month.

At least one of the executives at that pivotal meeting expressed concern about the future of Steinberg Limited after Sam Steinberg’s departure. “The company was built up around his leadership, and our assumption was that he would be around forever,” says his Harvard University-educated nephew, Arnold Steinberg, the vice-president of administration.

Succession was a not the only issue on the table. Some of the participants regarded the meeting as an unprecedented opportunity to restructure the company and shift power into the hands of senior executives.

Apart from Arnold Steinberg, the executives in attendance included Jack Levine, the head of the Quebec division; Mel Dobrin, the director of retailing and Steinberg’s son-in-law; Oscar Plotnik, the chief of the Ontario division; Irving Ludmer, the vice-president of expansion and development; John Pare, the vice-president of personnel; James Doyle, the head of the legal department; Harry Suffrin, the vice-president of organizational development; Guy Normandeau, the vice-president of manufacturing, and Steinberg’s brother, Nathan, a senior vice-president.

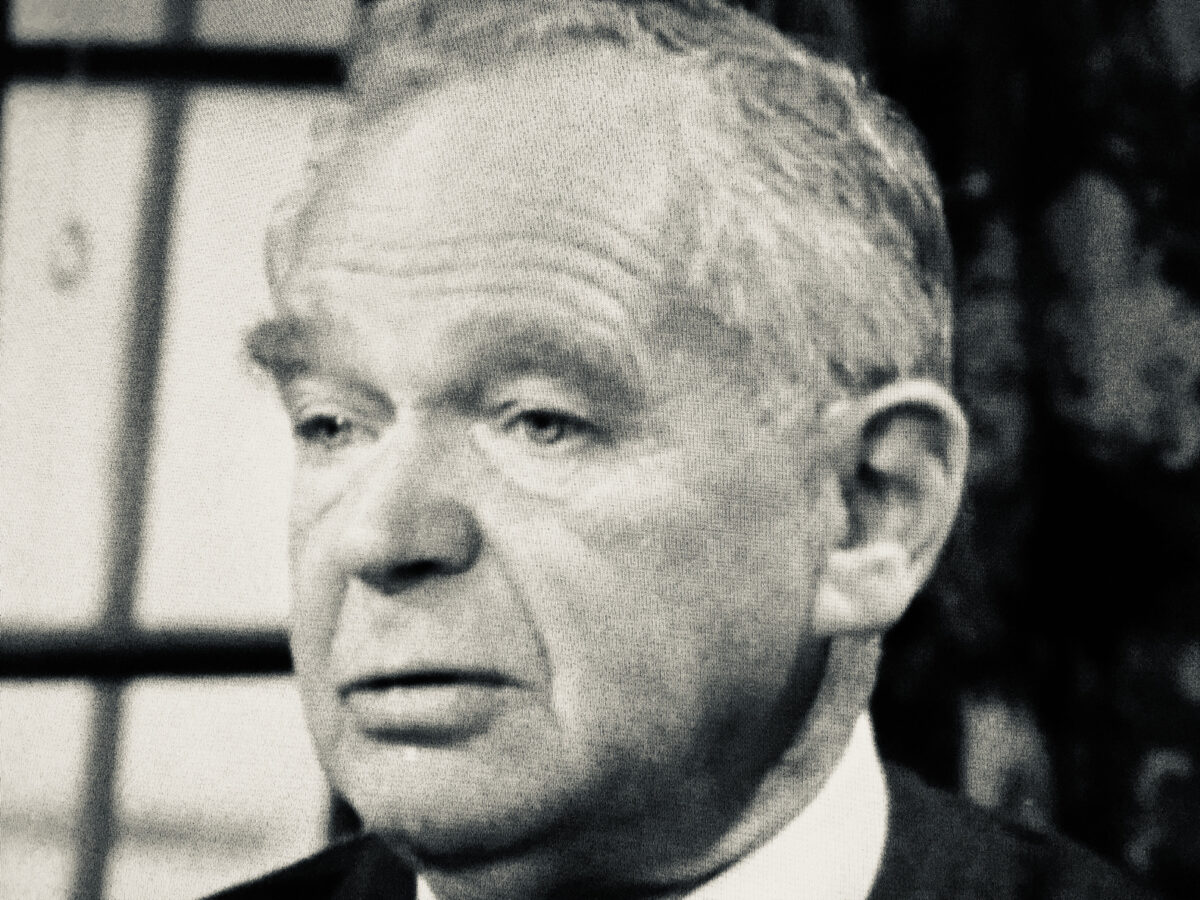

They rehashed the issues at hand and offered suggestions on how best to streamline the company so as to enhance profits. Sam Steinberg, a diminutive and even-tempered person, listened intently to his lieutenants and made the occasional comment. Midway through the session, he said he was “very pleased” by the direction of the discussions.

During lunch breaks, Sam Steinberg’s perky, ever-smiling wife, Helen, his distant cousin, walked around the room ladling out fresh salad into the executives’ plates.

Since Steinberg was a family enterprise, with sons, daughters and an assortment of relatives serving in various capacities at head office and in the stores, no one in the room was surprised when several of the managers raised a potentially delicate issue — nepotism.

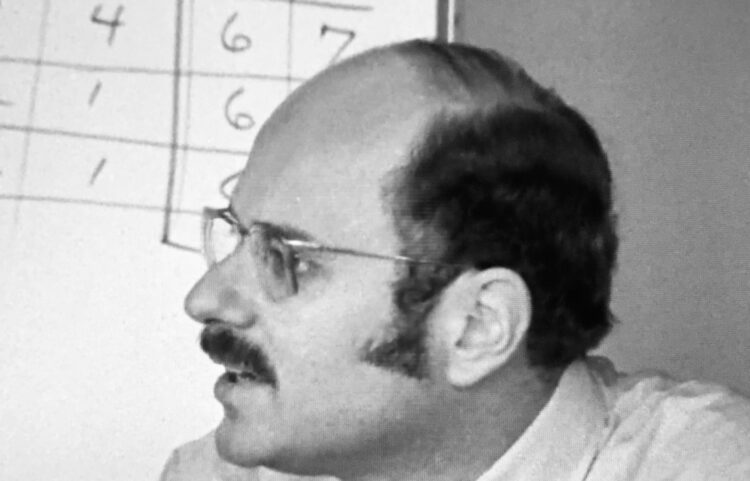

Ludmer, probably the youngest person at the meeting, said that key decisions were being made at Friday night Steinberg family dinners rather than at company headquarters. Doyle claimed that non-family executives were regarded like “negroes.”

Arnold Steinberg made two points. While he admitted that Steinberg had suffered due to nepotism, he insisted that family members should not be excluded from company jobs. In reply, Sam Steinberg said that all employees were judged by competency and ability.

Toward the close of the meeting, he informed his colleagues that the matter of succession would be settled within three to six months. Four months later, he announced the name of the next president.

Sam Steinberg stayed on as chairman of the board. “I’ll always be a driving force,” he said as his car left the lodge. “Always.”

In the next four years, the company’s revenues doubled. Sam Steinberg died of a heart attack in 1978. He was 72.

Steinberg dissolved into bankruptcy in 1992, three years after being sold to private interests.

My mother and I were saddened by the demise of a company that had served its customers exceedingly well.