Hugh Llewelyn Glyn Hughes, a British army doctor, and Rachel (Ruth) Genuth, a Hungarian Holocaust survivor, never met, but their paths crossed in the Nazi concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen in the spring of 1945.

Hughes was one of the first British officers to enter Bergen-Belsen. “I have been a doctor for 30 years and seen all the horrors of war, but I have never seen anything to touch it,” he said in shock after a tour of the camp.

Genuth, a teenager from northern Transylvania, arrived in Bergen-Belsen a month before Hughes. She contracted typhus there, but thanks to Hughes’ relief efforts, which could spell the difference between life and death, she survived.

Genuth’s daughter, Bernice Lerner, weaves these related stories together in All the Horrors of War: A Jewish Girl, A British Doctor, and the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen (John Hopkins University Press), a thoroughly-research, poignant book that draws on Hughes’ papers, oral histories, interviews and war diaries.

The story begins in the Romanian town of Sighet, which was annexed by neighboring Hungary, an ally of Germany, in the autumn of 1940. The Jews of Sighet, comprising 40 percent of its population, were relatively safe until the spring of 1944, when the Hungarian government began deporting Jews to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in southern Poland.

Genuth, the second of six children, was the daughter of a produce trader who had been conscripted into the Hungarian army as a laborer in 1942.

She and her family were deported on May 16, sharing a crowded freight wagon with 80 people. Within three weeks, 289,357 Jews from Transylvania and Ruthenia were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Tens of thousands of additional Hungarian Jews were killed before Hungary stopped the deportations in July 1944.

Genuth’s parents and most of her siblings were murdered in Poland. Having survived Auschwitz-Birkenau, she was sent to Christianstadt, a slave labor camp in the Gross Rosen complex of sub-camps. Many of the women and girls in Christianstadt lanored in the forest, felling trees, lopping off branches and dragging stumps. Genuth toiled in an explosives plant.

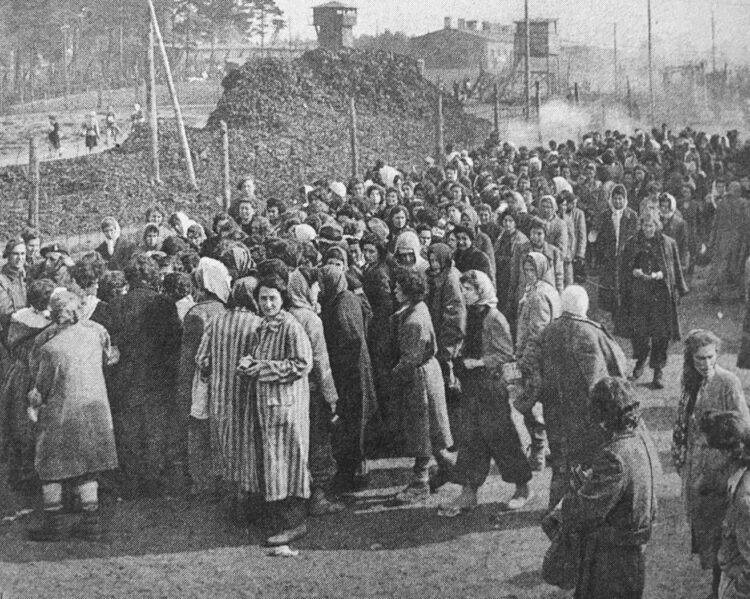

She and her sister, Elisabeth, reached Bergen-Belsen on March 15, 1945. Months earlier, a Dutch Jewish teenager named Anne Frank had been dumped in Bergen-Belsen, which was built to accommodate 4,000 prisoners but held 53,000 when the Genuth sisters arrived.

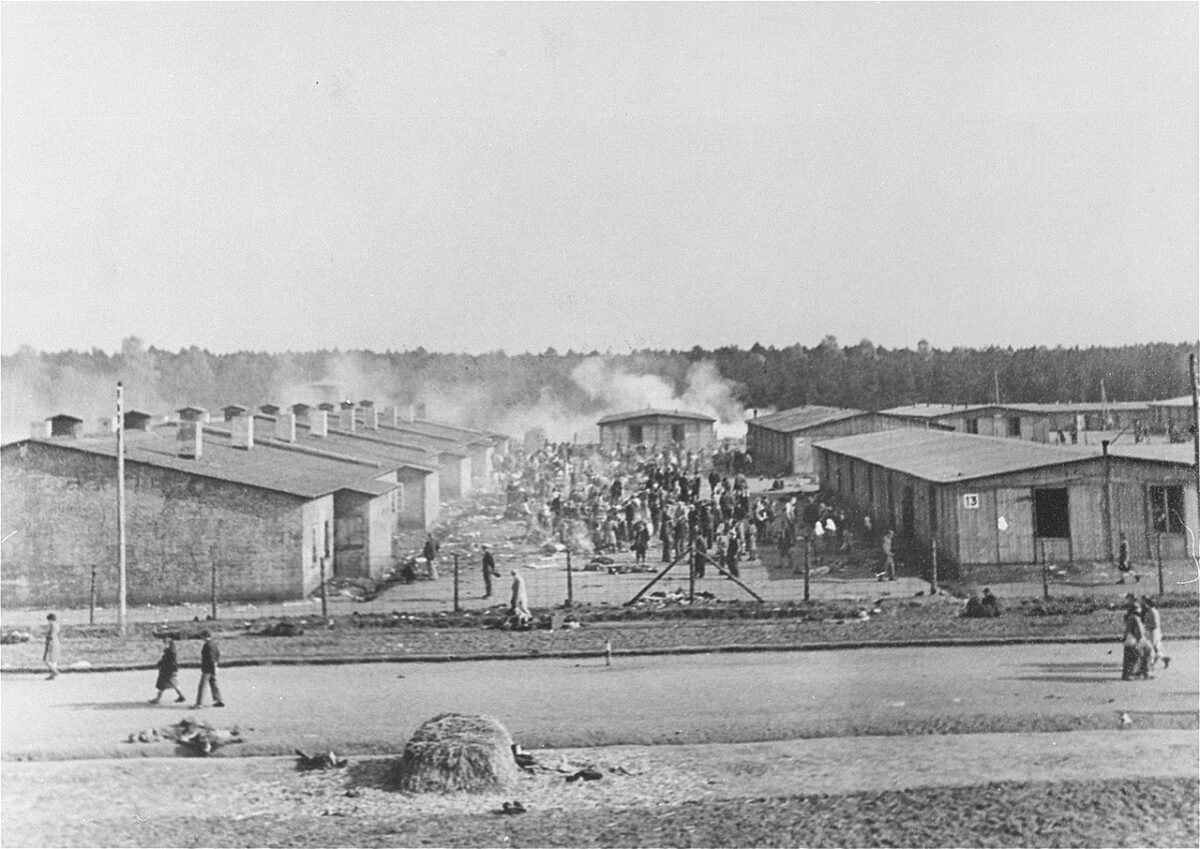

“The Germans did nothing to provide for the thousands of ravaged interns,” writes Lerner, a senior scholar at Boston University’s Center for Character and Social Responsibility. “No medical services. No habitable housing. No sanitation. No disposal of the dead, whose numbers increased with devastating speed.”

Like everyone else in Bergen-Belsen, Genuth quickly learned that maintaining personal hygiene was a task beyond reach. “It was impossible to clean oneself of mud and dirt, to get rid of the lice that burrowed everywhere. And that one could not escape the unbearable stench of decaying bodies, lying everywhere.”

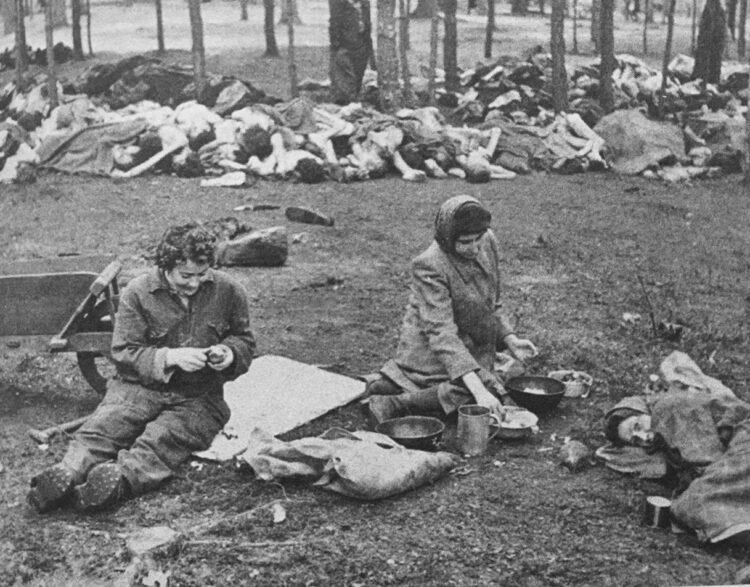

By the second week of April, the already horrendous situation degenerated even further. “No more flat cars came around to take away the corpses,” adds Lerner. “The distribution of food and water ceased. Those too weak to move relieved themselves where they sat or stood. Dead and dying lay everywhere, inside and outside the barracks.”

Anticipating Germany’s imminent defeat, the SS detachment in the camp attempted to tidy it up. Since its two incinerators were unable to cope with the mounting death toll, the SS piled bodies into funeral pyres to be set on fire. When local residents complained about the terrible smell, the SS forced prisoners to dig large pits where deceased prisoners would be buried. The plan could not be completed due to the overwhelming number of corpses.

Faced with a looming disaster, four German officers, waving a white flag, approached the headquarters of Britain’s Second Army in the nearby town of Celle to convey an important message: Sanitation in Bergen-Belsen had broken down, creating a potentially dangerous health hazard. Prisoners who escaped could spread disease, so it was in both sides’ interest to work together, the Germans advised.

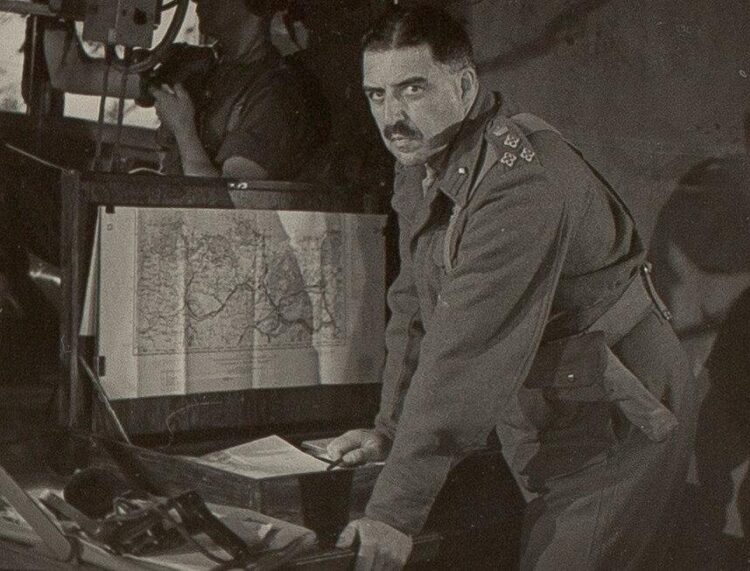

The British agreed. Soon afterward, Hughes, the 53-year-old deputy director of medical services of the Second Army’s 8 Corps, was instructed to bring back a report from Bergen-Belsen, the only German concentration camp formally turned over the Allies.

Hughes, a brigadier-general, and several of his colleagues entered Bergen-Belsen in mid-April, when battles were still raging in northwestern Germany. The camp’s commander, Josef Kramer, met the visitors.

Piles of corpses lay everywhere and ramshackle huts were filled to the bursting point with inmates, their eyes sunken in gray faces. Of 41,000 survivors, 70 percent required hospitalization. As Hughes learned, 17,000 prisoners had died during the previous month.

Hughes found large stocks of medical supplies in the camp and procured an additional 135 tons from the surrounding area. He also discovered a fully-equipped and staffed German military hospital, plus a functioning bakery, in the vicinity.

Apart from providing food, water and cleaning supplies to the prisoners, Hughes managed to eradicate typhus in the camp. He received assistance from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and the Red Cross, and pressed German doctors and nurses into service.

In the aftermath of Bergen-Belsen’s liberation, 13,000 survivors died. Some expired after the SS compelled them to eat bread baked with broken glass. In several instances, SS men and women were forced to bury the dead with their bare hands.

Richard Dimbleby, a BBC correspondent, broke down five times during two hours of reporting. References to Jews were edited out of his early broadcasts. British officials, hoping the prisoners could be repatriated to their countries of origin, categorized them by nationality only. Britain tried to discourage them from settling in Palestine, a British mandate. Britain’s efforts were resisted by Josef Rosensaft, a Polish Jewish survivor and a leader of the camp’s displaced Jews.

Rosensaft and other survivors hailed Hughes’ work, praising his compassion and gentleness in treating the sick. In gratitude, they named a nearby hospital after him.

Several months after Bergen-Belsen’s liberation, Hughes testified at what would be the first war crimes trial following Germany’s surrender. It took place in Luneburg, a short drive from the camp. Thirty one members of the SS were pronounced guilty and 14 were acquitted. Eleven of the convicted criminals were hanged, including Kramer. No effort was made to catch scores of Nazi guards who had fled Bergen-Belsen before it was liberated.

After the trial, Hughes, aspiring to a career in the army, applied for a permanent position. He was rejected, even though he had been awarded the Order of the British Empire and had received a personal letter from U.S. President Harry Truman praising his humanitarian contributions.

In postwar Britain, Hughes was employed by a London hospital and helped build a national health care service. He visited Israel in 1965 for a joyous reunion with survivors. In 1970, he joined Rosensaft on a pilgrimage to Bergen-Belsen’s mass graves. Hughes died in 1973.

As for Genuth, she recovered and spent the years immediately after the war in Sweden. She married a fellow survivor and they joined her sister in the United States.

Genuth would never meet Hughes, but she doubtless owes her life to the man who played such a pivotal role in saving thousands of Jews in Bergen-Belsen, among whom were my late parents, David and Genia Kirshner.