The recent release of the once-inaccessible archive of the United Nations War Crimes Commission, dating back to 1943, by the London-based Wiener Library, the world’s oldest Holocaust archive and Britain’s largest collection on the Nazi era, has reignited an old debate.

How much did the Allies know during World War II that Adolf Hitler’s genocidal regime was murdering millions of Jews? And could they have stopped it, or at least slowed it down?

Access to this vast quantity of evidence was timed to coincide with the publication of Human Rights After Hitler: The Lost History of Prosecuting Axis War Crimes, by Dan Plesch, a researcher who had been working on the documents for a decade.

Referring to the release of the documents, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu weighed in, stating in an address on Yom Hashoah (Holocaust Memorial Day) at the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem on April 23 that four million Jews could have been saved had the Allies bombed the Nazi extermination camps and the rail lines leading to them.

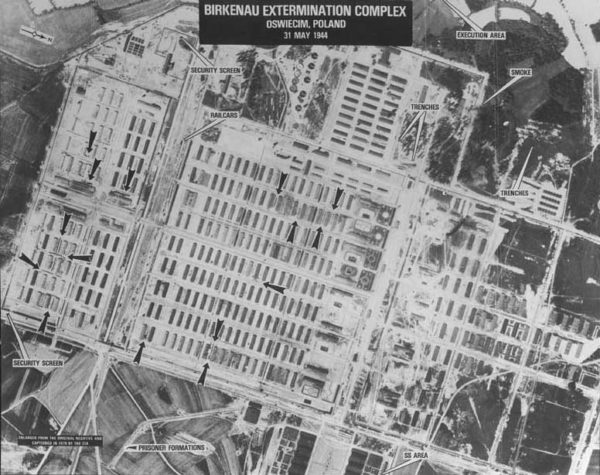

“When terrible crimes were being committed against the Jews, when our brothers and sisters were being sent to the furnaces,” he told the audience, “the powers knew and did not act.” After all, aerial reconnaissance photographs of Auschwitz were actually taken by the U.S. Air Force in 1944.

All of this is not really a new revelation. Netanyahu was referring to the fact that the Polish underground, among others, had been providing the Allies with detailed information about the Nazi death camps located in their country, such as Treblinka and Auschwitz-Birkenau, where millions of Jews were gassed, as early as 1942.

On December 10, 1942, the London-based Polish government-in-exile published an official Polish protest, titled “The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland.”

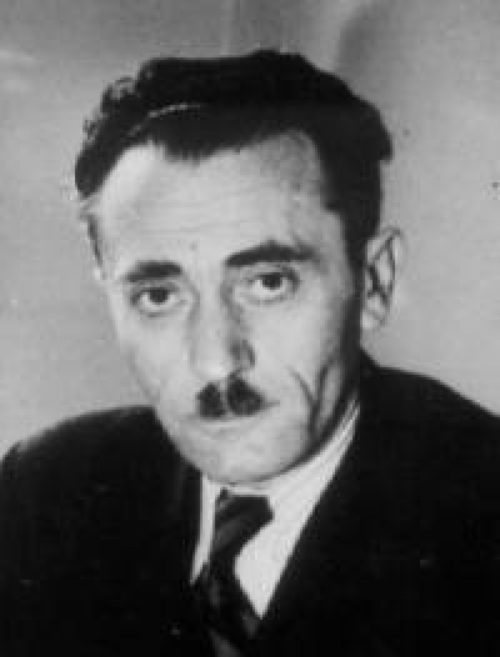

Indeed, to publicize these findings, Shmuel Zygielbojm, a prominent Polish Jewish leader who had escaped Poland in December 1939, committed suicide in London on May 11, 1943, to protest the indifference of the Allied governments in the face of the genocide.

When I was researching my PhD dissertation for the University of Birmingham in the 1970s, and reading the British press from the war years, it was clear that saving Europe’s Jews was not a high priority. Since that time, numerous books and journal articles have documented the lack of efforts to save the doomed Jews of Europe.

I can do no better than to cite my own thesis, later published as a book in 1995:

Following the revelations of Nazi mass murder in 1942, Britain’s chief rabbi, J.H. Hertz, lamented that “the silence of large sections in this country had been taken by the Nazis as an encouragement to continue their techniques of annihilation.”

And though British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden described the ongoing genocide to the House of Commons on December 17, 1942, little was done. Indeed, 16 months after Eden’s speech, one newspaper on April 28, 1944 complained that “the indignation is cold and the promise of retribution is forgotten.”

So Netanyahu was right — in fact, the Allies could have saved all six million Jews by defeating Hitler before 1939, when the Nazi state was not yet that powerful.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the Unversity of Prince Edward Island.