A major schism is looming between the two largest Jewish communities in the world, those in Israel and the United States. Together they constitute some 85 percent of the world’s Jews. For a number of political, religious and sociological reasons, they are drifting apart.

It isn’t the first time this has happened in the long history of the Jewish people. After all, arguably the most significant split occurred almost two millennia ago, between the followers of Jesus and those who rejected him as the messiah.

In our time, the future of world Jewry will likely be shaped by these two largest populations, and by the relationship between them. For that reason alone, the waning of attachment to Israel among American Jews, especially but not exclusively younger American Jews, has rightly become a matter of concern.

Some blame the growing estrangement on Israel, others on the American Jewish community.

Today, while most American Jews embrace a political theology of prophetic Judaism and consider themselves cosmopolitans, they see in Israel an ethno-national state” moving in an increasingly illiberal direction.

Others point the finger at American Jewry, noting the loosening of once-powerful communal bonds, as evidenced by the high rates of intermarriage and the move away from Jewish religious affiliation, as well as the erosion of communal memory, especially of the Holocaust era and the history of the state of Israel itself.

Increasingly, writes Professor Daniel Gordis of Shalem College in Jerusalem, author of the 2016 book Israel: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn, the orientation of many American Jews toward Israel is one neither of instinctive loyalty nor of pride but of indifference, embarrassment, or hostility.

The findings of a 2013 Pew Center study, A Portrait of Jewish Americans, confirms this: While nearly 40 percent of American Jews aged sixty-five or older continue to feel “very attached” to Israel, only 25 percent of eighteen-to-twenty-nine-year-olds feel the same way.

At the opposite pole, of those not “very attached” to Israel, the gap is even wider, with twice as many younger as older Jews claiming that status.

Political views are another important variable. Half of Republican Jewish respondents describe themselves as “very attached” to Israel, but only a quarter of Jewish Democrats do so. On the other hand, while only two percent of Jewish Republicans describe themselves as “not at all attached” to Israel, among Jewish Democrats the number is fully five times higher.

Along the religious spectrum, the same holds true: while 77 percent of Modern Orthodox Jews describe themselves as “very attached” to Israel, on the left, the comparable figures are drastically lower: only 24 percent for Reform Jews and 16 percent for those claiming no denominational affiliation.

The Reform movement, in particular, is a blend of liberal theology and progressive politics. One wag parodied it as “the Democratic Party with holidays thrown in.”

In brief, concludes Gordis, the group growing most disconnected from Israel is composed of younger, politically more left-leaning, and religiously less traditionalist American Jews.

For them, not just Israel’s policies, but its very essence is objectionable. As opposed to American universalism, ethnic particularism is at the core of Israel’s very reason for being. And the public square, rather than being religiously neutral, is in Israel suffused with Judaism, something even most non-observant Israeli Jews accept.

Farther on the left, intersectionality is the dogma of the progressive left. In theory, it’s the notion that every form of social oppression is linked to every other social oppression.

You might imagine that the Jewish people, age-old victims of antisemitism, might be seen as victims, along with those oppressed because of gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, and so forth.

You would be wrong. Why? Because of Israel, which progressives see only as a vehicle for oppression of the Palestinians.

Jewish students, often ill-prepared to counter such views, are exposed to this at liberal arts institutions, at a formative stage of their lives.

“For progressive American Jews,” observed Barry Weiss in the June 27 New York Times, intersectionality forces a choice. “Do you side with the oppressed or with the oppressor?”

Many American Jews have increasingly picked liberalism and left-wing politics over Judaism.

The chasm will continue to widen. After all, as the American-born Israeli novelist Hillel Halkin reminds us, the two populations live in different worlds, speak different languages, face different problems, have different life experiences, and adhere to different values.

For Israelis, their Jewishness, notes the secular Israeli author A.B. Yehoshua, is something fixed and permanent, not something transient and only mobilized when convenient, increasingly the case for American Jews.

When the Israeli cabinet recently froze a plan to designate a space for mixed-sex prayer at the Western Wall, Judaism’s holiest site, in Jerusalem, a great many saw in this a rejection of American Jewry by the Jewish state. It was done to placate the Orthodox. But the rejection may be mutual, since most American Jews are either secular or in non-Orthodox streams.

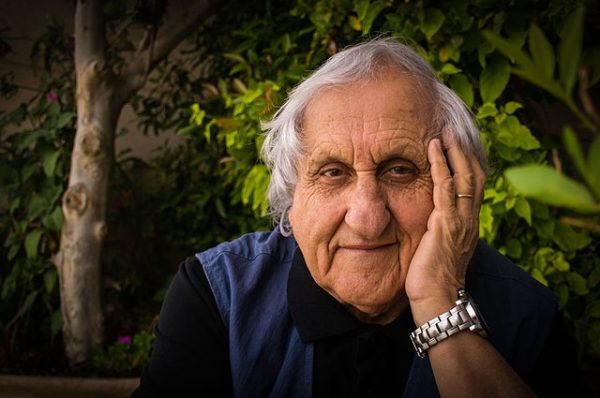

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.