Iraq is imploding.

The Sunni jihadis of the group known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria have moved to within sight of Baghdad, while the Shi’ite government of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki becomes more dependent than ever on Iran.

More and more, even Americans — who suffered tens of thousands of soldiers killed and wounded during their occupation of the country between 2003 and 2011 — are staring the obvious in the face: Iraq is really composed of three mutually hostile groups: Arab Sunnis in the center, Arab Shi’ites in the south, and Kurds in the north.

With talk of partition, has the moment of historical opportunity finally arrived for the Kurds, the largest ethnic group in the world without a state of its own? Will one of the results of the current chaos be the formation of a sovereign entity on Kurdish territory?

A non-Semitic but Muslim group of some 25 million people, the Kurds live in eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, northern Syria and northwestern Iran.

Their tribal lands were divided up after World War I by the new colonial powers in the Middle East — Britain and France.

Initially, under the Treaty of Sevres, signed in 1920 between the defeated Turkish Ottoman sultan and the victorious Allies, Turkey was to grant autonomy to Kurdistan.

However, a new Turkish leader, Kemal Ataturk, emerged, mobilized the Turkish nation, and forced the abrogation of the treaty. It was superceded by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which completely ignored Kurdish national aspirations.

Instead, the Kurds became a minority in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. In all these countries, their ambitions for national independence were regarded as threatening and Kurds advocating independence faced prosecution. They were told they were now Iraqis, Syrians or Turks.

Today, about half the Kurdish people live in Turkey, the remainder in Iraq, Iran and Syria.

Kurdish rebels fought the Iraqi government in the early 1970s but the Kurdish guerrilla movement collapsed when neighboring Iran, Israel and the United States withdrew support in 1975.

In the 1980s, the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein, attacked Kurdish villages with poison gas. In the town of Halabja alone at least 5,000 people died in one attack in March 1988. Saddam also forced Kurdish residents out of Kirkuk, a traditionally Kurdish city, and brought in Iraqi Arabs to take over their property.

After the 1991 Persian Gulf War, the United States and Britain established a so‑called “no‑fly zone” above the 36th parallel in northern Iraq, allowing Kurds in that region to establish a de facto autonomous jurisdiction with a fair amount of internal democracy.

The defeat of Saddam by the United States in 2003 enabled the Kurds to strengthen their hold on Kurdish-majority areas. Though divided into two major political groupings, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which were often at odds, the Kurds presented a united front in their efforts to gain control of northern Iraq.

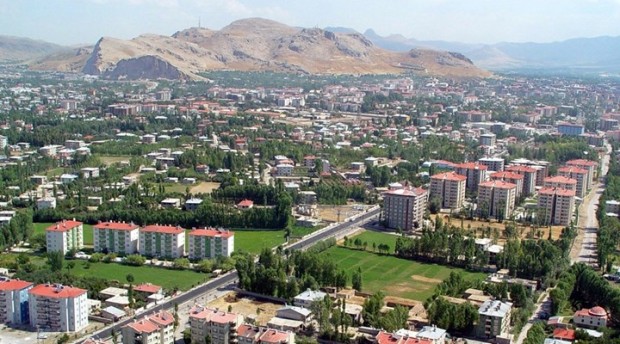

Iraqi Kurdistan is now virtually independent, with its own flag, executive, legislature and judiciary. Its capital is Erbil (sometimes spelled Arbil).

Last September, Iraqi Kurdistan held its fourth legislative election for the 111-seat Kurdish National Assembly, with the KDP winning 38 seats to the PUK’s 18. A new opposition group, Gorran (the Movement for Change), which split off from the PUK, took 24, while two Islamic parties won another 16.

However, since the parliamentary elections held in 2005, the KDP and PUK have ruled the Kurdish region as a united government, though the KDP has had the upper hand. Massoud Barzani, president of the Kurdish Region and son of the famed rebel leader Mustafa Barzani, heads the KDP. The PUK’s leader is Iraq’s President Jalal Talabani, who has been ill and holds little power in that largely ceremonial position.

Still formally a part of Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan has long been at odds with Maliki over unresolved issues of oil, money and power. The Kurds claim that he has consolidated all powers into his own hands and violated the constitution that was drafted and voted for by all Iraqis in 2005. The KRG also wants the right to export Kurdistan’s oil independent of Baghdad, and demands the 17 percent share of the Iraqi national budget that it claims it has never received in full.

Taking advantage of the turmoil in Iraq, the Kurdish military, known as the Peshmerga, has now seized large tracts of Kurdish-populated territories that had remained disputed and outside its control including Kirkuk, which the Kurds regard as their “Jerusalem” and see as a future capital.

Capturing the city and its huge oil reserves, just outside the area controlled by the Kurdish regional government, is a huge achievement. In Mosul, Sunni insurgents have gained control of the area on the west bank of the Tigris River, the Kurds on the other side.

Will the Kurds be able to gain — and retain — cities such as Kirkuk and Mosul, surrounded by oil-rich areas that would enable a Kurdish state to become economically self-sufficient, indeed wealthy?

In two decades of de facto autonomy in Iraq’s north, the Kurds have proved they can run a civil state. And they have oil, which would go a long way in providing economic stability.

The Iraqi Kurds also seem to have overcome Turkish hostility towards their project. Because 20 percent of the Turkish population is Kurdish, Ankara historically feared that an independent Kurdish state would further aggravate separatist sentiment among Turkish Kurds.

Turkey suppressed Kurdish efforts to maintain a separate ethnic identity. Kurdish language publications were banned until 1995 in Turkey and even the teaching of the Kurdish language was largely prohibited.

Abdullah Ocalan, leader of the Kurdish separatist insurgency inside Turkey, was arrested in 1999 and initially condemned to death. His sentence was later reduced to life imprisonment.

But last year Ocalan called on his followers to cease armed struggle against the Ankara regime, a move welcomed by Turkey’s current prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The Turkish government has demonstrated its willingness to recognize Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) leader Ocalan as a legitimate negotiator for the Turkish Kurds.

This has also benefitted the Kurds on the Iraqi side of the border. No longer is Ankara adamantly opposed to a Kurdish polity in northern Iraq (which included periodic military operations in the region by the Turks).

Ergogan, a religious Sunni, is also no friend of the Shi’ite regime in Baghdad (nor the ones in Damascus and Tehran either). In April 2012, Erdogan called Maliki “self-centered” and accused him of stirring sectarian conflict. In reply, Maliki denounced Turkey’s behavior as that of a “hostile state.”

So Ankara is in the midst of an unprecedented rapprochement with the Iraqi Kurds, one that has come largely at the expense of the Maliki government. The KRG cleverly offered Turkey various enticements, such as granting major construction projects to Turkish companies, including at the Erbil and Sulaymaniyah airports.

Ankara and Erbil have now built strong economic and diplomatic relations. They have signed a 50-year energy deal and Kurdish oil is being exported via a pipeline that connects the autonomous region to the port of Ceyhan on the Mediterranean. Turkey is now the KRG’s main business partner, and 80 percent of Kurdish consumer imports come from there.

Last November Erdogan met with KRG President Barzani in the largely Kurdish-populated city of Diyarbakir in southeastern Turkey. The city was adorned with Turkish and KRG flags. Barzani addressed the crowd in Kurdish standing next to the Turkish prime minister and Erdogan for the first time ever, according to onlookers, pronounced the word “Kurdistan.”

Earlier this month, Huseyin Celik, a spokesman for Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), declared that the Kurds of Iraq have the right to decide the future of their land. “Turkey has been supporting the Kurdistan Region,” he said, and will continue to do so.

This is probably the best chance the Kurds have had in 80 years to form a sovereign state in at least a part of their historic patrimony. They are certainly laying the groundwork for it.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.