Amsterdam’s old Jewish quarter, the Jodenhoek, is but a hollow shell of its former self, having been swept away by the tides of time.

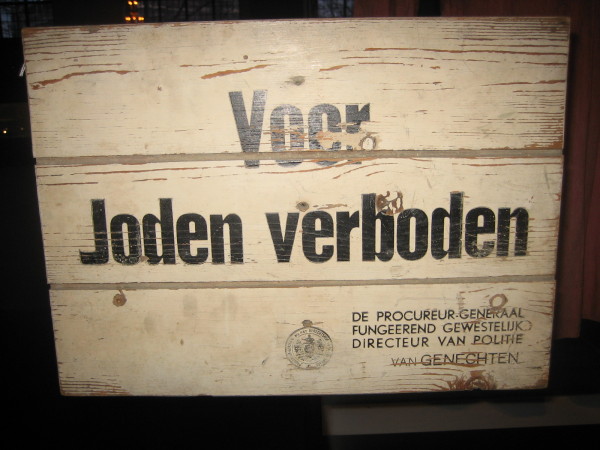

The epicenter of the Jewish community from the 17th century until World War II, it was once a congested and atmospheric labyrinth of tenements, factories, open-air stalls, narrow streets and back alleys. But with the Nazi occupation of Holland, the Jodenhoek was doomed to extinction.

When the Germans marched into Holland in May 1940, more than half of its registered 140,000 Jews lived in Amsterdam, a lively, sophisticated city known for its romantic canals, exquisite architecture and great art museums.

The Jodenhoek survived the German occupation, but it was virtually emptied of its Jewish inhabitants during the Holocaust, which consumed 78 percent of Dutch Jews. After the war, the Jodenhoek was subjected to a thoughtless sterile redevelopment program which destroyed its flavor and spirit.

Although it has been completely drained of its distinctive pre-war character, tourists are still drawn to the Jodenhoek, which was settled by crypto-Jews and Sephardic Jews after the Spanish Inquisition and by Ashkenazic Jews following late 19th century pogroms in the Russian empire.

Probably the most historically important building in the Jodenhoek is the venerable Portuguese Synagogue. Known as the Esnoga — the word for synagogue in Portuguese — it’s a bulky structure clad in brown bricks. As its name suggests, it was founded by Portuguese Jews, many of whom were merchants and traders who played a role in the expansion of the Dutch empire in the 17th century.

The Portuguese Jews were, in fact, Spanish Jews, but since the Dutch republic was then at war with Spain, they preferred to be identified as Portuguese rather than Spanish.

Designed by Elias Bouman in a Neoclassical style, the Portuguese Synagogue was inaugurated in 1675, and has been regularly renovated since then.

The interior is imposing. Originally, the floor was covered with fine sand, but hardwood has replaced it. The wooden ceiling is supported by four thick stone columns. Golden brass chandeliers, with more than 1,000 candles, illuminate the benches. Women’s galleries, with separate entrances, face each other.

The south side of the synagogue faces a square named after the first practising Jewish lawyer in Amsterdam, Jonas Daniel. From here, in February 1941, 400 Jewish men were deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. The illegal Communist Party protested the roundup and called a strike, which was honored by transport and dock workers.

The Jewish Historical Museum, located on the opposite side of the square, is a fusion of four restored synagogues that were last used in 1942. Focusing on Judaism and Jewish culture, the museum tells the story of Dutch Jews through books, photographs, oil paintings by Jozef Israels — a major 19th century painter and graphic artist for whom a street in Amsterdam is named — ritual objects, marriage contracts and a short film of the Jodenhoek made in 1932.

The museum is close to Jodenbreetststraat, Broad Street of the Jews, the locale of Rembrandt House. The Dutch painter crafted his most famous canvas here, The Night Watch.

A few streets away, on St. Anthoniebreetstraat, stands a regal white Italian Renaissance building. The former residence of Isaac de Pinto, one of the wealthiest Jews of the 17th century, it’s now a library.

Waterlooplein, Jodenhoek’s central market from 1886 onward, is currently the site of Amsterdam’s largest flea market, a warren of stalls brimming with clothes, household items, books, records and antiques.

A statue of Baruch Spinoza, the heretical philosopher excommunicated by the Jewish community, stands next to Amsterdam’s city hall. So does a black marble monument dedicated to the Dutch Jews who resisted the Nazi juggernaut.

The Hollandsche Schouwburg, in the leafy and sedate Plantage district, is probably the single most important memorial commemorating the Holocaust in Holland. Many Jews resided in Plantage before the war. From August 1942 to November 1943, the Nazis used the late 19th century theater as a deportation center.

The theater was demolished in 1962, but four brick walls were left standing and they pay homage to the 107,000 Dutch Jews murdered during the Holocaust. On the walls are black and white photographs of pre-war Jewish life in Holland.

An annex documents the Holocaust through photographs and artifacts.

Another Holocaust site worth visiting is the Wertheim-Plantsoen Park, named after a 19th century Jewish businessman. Within its grounds is a memorial honoring the victims of Auschwitz. It’s composed of seven large panes of broken glass.

Across the street, at 58 Nieuwe Keizergracht, is a hotel with a grim history. The elegant cream-colored building housed the wartime Joodse Raad, or Nazi-appointed Jewish Council. Established in 1941, the Jewish Council was headed by Abraham Asscher, a diamond merchant, and David Cohen, a university professor.

Prior to the war, Holland’s diamond industry was dominated by Jews. The Asscher Diamond Company was among the largest firms of its kind in the country.

Anne Frank, the renowned Jewish diarist who died in Bergen-Belsen, is the human face of the Holocaust in Holland. A museum, housed in a mid-town building where she and her family took refuge, honors her short but remarkable life.