To the author Haim Bresheeth-Zabner, the armed forces of Israel stand at the core of Israeli society. The creation of the Israel Defence Forces, or IDF, was the most important priority facing Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, after he declared statehood on May 14, 1948.

Since its formation on May 26 of that fateful year, the IDF has been of paramount importance to the Jewish state in securing its existence. Beyond its indispensable role in safeguarding the nation, he adds in his book, An Army Like No Other (Verso), “The IDF and the social, financial and cultural apparatus connected with it form the single most important institution in Israel — a politico-cultural-economic (and) military-industrial complex.”

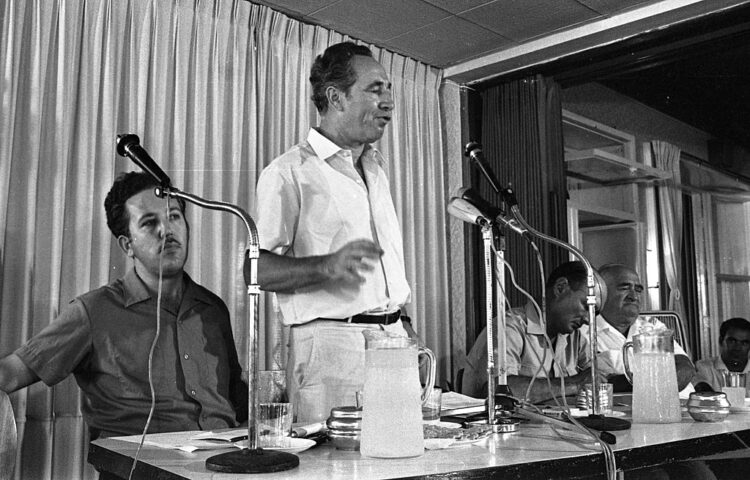

This complex constitutes Israel’s largest economic sector, employing hundreds of thousands of scientists, engineers and researchers directly or indirectly. Shimon Peres, the director-general of the Ministry of Defence in the 1950s, was instrumental in its creation.

In addition, the IDF has been heavily invested in cultural production in moulding a national identity, says Bresheeth-Zabner, a former Israeli and now a researcher at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London.

The IDF founded Galei Zahal, a popular radio station, and Ba’Machane, a widely read weekly magazine. And it financed musical and dramatic troupes, which became training grounds for actors, singers, playwrights, directors, producers and designers of Israeli film, theater and television.

The IDF has also been a driver of research and development in software and hardware in Israel’s eight universities and 20 colleges.

And retired IDF officers, notably Moshe Dayan, Yitzhak Rabin, Ezer Weizman and Ariel Sharon, have gone into national politics. “There is always a place of honor and influence for a retired general in political parties,” he writes. “Indeed, a military career seems to be the required preparation for Israeli politicians. Those who, like Benjamin Netanyahu, were not senior officers find it necessary to highlight their military achievements.”

Above all, the IDF has enabled Israel to expand its boundaries, not only during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war but during the 1967 Six Day War as well.

Due to its lack of strategic depth, Israel adopted an offensive doctrine. “The IDF prefers attack to defensive measures,” he writes. “Israel has always preferred to strike first, and its military philosophy and practice is attuned to this need. Transferring the battle to enemy territory has become the IDF’s first tenet, inherited from the offensives of 1948.”

In his view, Israeli state and society have been formed by militarism since the earliest phases of Zionism. “Israelis perceive themselves as soldiers, whether during the long compulsory service that begins in the late teenage years for both sexes, or later, throughout adult life, in the reserves,” he says. “Indeed, military training does not start at eighteen, but at the age of fourteen, when high school kids join the Gadna youth battalions and start their preparations for army life.”

Bresheeth-Zabner himself is a veteran of the Israeli army, having been a second lieutenant in a brigade command during the Six Day War. The son of Polish Holocaust survivors, he and his parents arrived in Israel in 1948. En route to their new home, his father, a Bundist in pre-war Poland, refused to partake in weapons training.

A draft resister, he was arrested as a conscientious objector on arrival in Haifa, but agreed to serve as a medic and participated in the fierce and costly battle of Latrun.

“My parents and I were hardly willing colonialists,” he says in the first glimmer of his anti-Zionist creed. “But living as part of the colonial project, they were normalized into its ranks, and later also accepted its rationale and methods.”

He, however, needed “to get out” of Israel. While studying at the Royal College of Art in London in the early 1970s, he met members of Matzpen, the radical anti-Zionist Israeli organization, and this experience transformed him. “It allowed me to resolve my identity and beliefs and freed me from the all-powerful, stifling collectivities of Zionism.”

Bresheeth-Zabner’s assessment of Israel is nothing if not harsh. Describing Israel as “a settler colonial project” and “a client state of the West … with some autonomy,” he argues that it “cannot be a real liberation site for Jews” because it denies the rights of the indigenous Palestinian Arabs. “As Marx noted, ‘No nation can be free if it oppresses other nations.'”

Antisemitism is “crucially important” to Zionism because it creates Zionist recruits and impels them to settle in Israel. “Without antisemitism, Zionism is a spent historical force” because most Jews will forego aliyah unless they face a direct threat in their native states.

Nonetheless, Zionism puts Jews in harm’s way: “This makes Israel the only country in which Jews live in mortal danger because they are Jewish (and colonialists, militarists, occupiers and racists).” As far as he is concerned, Israel is an apartheid state.

This is a one-dimensional, incomplete and unfair appraisal of Zionism and Israel. Yet his survey of the origins and history of the IDF is useful.

Early 20th century Zionists in Palestine formed self-defence units as tensions between Jewish settlements and Arab villages mounted. This led to the formation of Shomrim in 1907 and Hashomer in 1909. The Haganah was founded 11 years later.

During the opening phase of the War of Independence, Ben-Gurion merged all the Jewish militias to create the IDF. Bresheeth-Zabner uncharitably calls it “a centralized, authoritarian, ideological and professional body — an instrument of occupation, expulsion and subjugation.”

He dredges up a quotation from Dayan to illustrate his claim. On the eve of the Six Day War, Dayan said, “The IDF is a decidedly aggressive assault army in the way that it thinks, the way that it plans, the way that it implements. Aggression is in its bones and its spirit.”

Denigrating Dayan as a warmonger, he claims that Dayan attempted to suck Arab states into conflict with Israel by means of retaliatory raids so that it could conquer the Sinai Peninsula and the West Bank and destroy Egypt’s army. “Dayan was prepared to take unnecessary risks in a small country without strategic depth,” he says.

He argues that Israel’s imperial alliance with Britain and France in the 1956 Sinai war was proof of its value as an ally of the West in the region. Israel emerged from that war stronger than before.

He suggests that Israel should be held responsible for the outbreak of the Six Day War, which, he contends, transformed it from “a small and insignificant state into a regional and even a global player.”

Israel built the National Water Carrier, a major project to move fresh water from the Galilee to the Negev desert, despite its neighbors’ protests. Israel provoked friction by placing soldiers and armaments in demilitarized zones adjacent Syria and lured the Syrian Air Force into an aerial battle during which Israeli pilots downed seven Syrian jets. He admits that Syria’s support of Fatah terrorist operations against Israel stirred pre-war animosities.

Bresheeth-Zabner says the 1973 Yom Kippur War was the last war the IDF fought against an Arab army. Not true. Israel tangled with Syria during its invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

Having had to operate in civilian areas on an unprecedented level during the war in Lebanon, the IDF learned valuable lessons and invested in developing spy satellites, drones and what he calls “software solutions.”

He contends that Israel relied far too much on the air force to prosecute the second war in Lebanon in 2006. “The IDF command believed that the decisive effect of air power made the use of ground forces unnecessary. This proved to be an egregious error.” He adds that the IDF was unable to break Hezbollah’s fighting spirit, was taken aback by its agility and inventiveness, and was surprised by its ability to sustain its rocket campaign until the very last day of the war.

In summing up this war, he concludes, “It was the first war where civilians paid a higher price than the IDF. Northern Israel became prey to Hezbollah rockets, with normal life and work ceasing … and people trapped in bomb shelters.”

Israel’s peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan in 1979 and 1994 had a significant impact on the IDF. The treaty with Egypt removed the largest and best equipped and motivated Arab army from the equation. “From then on, Israel did not need to invest resources in combat with Egypt,” he says. The treaty with Jordan served the same purpose and enabled the IDF to focus on containing the Palestinians.

Bresheeth-Zabner points to another development that has changed the IDF beyond recognition. In the past, the officer corps was mainly composed of left-leaning nationalists, some of whom were raised on kibbutzim. In recent years, they have been gradually replaced by right-wingers from the national religious camp as Israel has moved incrementally to the right.