Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany has not flinched from the historically vital task of confronting the ghosts of her country’s ugly Nazi past.

In accordance with this steadfast spirit, Merkel visited Auschwitz-Birkenau on December 6. At this former German concentration camp in southern Poland, she spoke eloquently about the Holocaust and its legacy, Germany’s enduring responsibility to draw cautionary lessons from the Nazi interregnum, the need to preserve Holocaust sites before they crumble into dust, and the upsurge of racism that threatens the values of liberal democracy in this era of right-wing populism.

This was her first visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau, but it was not the first time she has visited a former Nazi concentration camp. In 2009, accompanied by U.S. President Barack Obama, she paid a visit to Buchenwald. In 2013, she went to Dachau in the company of survivors. She returned to Dachau four years ago to mark the anniversary of its liberation.

A strong supporter of Israel, she has visited Yad Vashem — the Holocaust memorial and educational center in Jerusalem — no less than five times.

Time and time again, she has proven herself to be a friend of Jews and of Israel (though her decision to admit more than one million Muslim refugees from 2015 onward may turn out to be very problematic).

At Auschwitz-Birkenau — where the majority of its 1.1 million victims were Jews — Merkel described the horror of the Holocaust as “unfathomable” and acknowledged that the perpetrators were Germans. “Auschwitz was a German death camp, run by Germans,” she declared with crystalline clarity and searing honesty. “I am filled with deep shame in the face of the crimes that were committed here by Germany.”

“We Germans owe it to the victims, and we owe it to ourselves, to keep alive the memory of the crimes committed, to identify the perpetrators and to commemorate the victims in a dignified manner,” she asserted.

And in a courageous remark that some Germans may find unsettling, she said, “This is not open to negotiations. It is an integral part and will forever be an integral part of our identity.”

In an implicit reference to a botched attack by a neo-Nazi thug on a synagogue in Halle on Yom Kippur, an assault she labelled as “a disgrace for our country,” Merkel said that Germany has a “duty to protect Jewish life” and to adopt a zero tolerance policy toward antisemitism. As she said, “antisemitism will not be tolerated.”

This condemnation of antisemitism was not just rhetorical or ritualistic.

Prior to her appearance at Auschwitz-Birkenau, which was liberated by the Red Army 75 years ago come January 27, the German government announced it will bear the cost of guarding every single synagogue in Germany. This is a necessity following the assault in Halle and the 10 percent increase in hate crimes against Jews last year.

In a nod to the upsurge of racism in Europe, Merkel spoke of the need for political leaders to remain committed to democracy, which, she lamented, is “very vulnerable and fragile.” As she put it, “These days, it is important to state this in an unequivocal manner because what we are experiencing of late is an alarming level of racism, increasing intolerance (and) a wave of hate crimes.”

Reaching the nub of her commentary, Merkel said, “We are witnessing and experiencing an attack on the fundamental values of liberal democracy.” And in a rebuke of Holocaust denial, she described “historical revisionism” as a kind of “hostility.”

This being the 10th anniversary of the creation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation, Merkel announced that Germany will donate $67 million to ensure that the camp/museum is preserved for future generations.

Merkel’s pilgrimage to Auschwitz-Birkenau was a reminder that two previous chancellors visited the camp.

Helmut Schmidt, a soldier during World War II, was the first German chancellor to set foot there. He arrived on an overcast day in November 1977, when memories of the Holocaust were still relatively fresh. “This is a place that commands silence,” he said. “Yet, I am certain the German chancellor cannot remain silent here.”

In his speech, which was broadcast live on Polish television, Schmidt drew one overarching lesson that is as applicable today as it was more than 40 years ago: “There is no escaping the realization that politics requires an ethical basis and a moral order.”

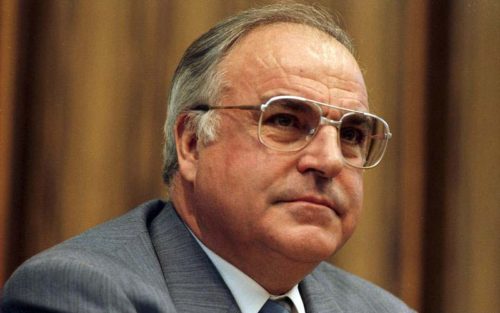

The next German chancellor to appear at Auschwitz-Birkenau was Helmut Kohl in November 1989, the month the Berlin Wall fell. Kohl, who was a teenager when the war ended, did not deliver a speech, but in the official guestbook, he wrote of the “unspeakable suffering” Germany had inflicted on so many people.

Deeply affected by his visit, Kohl later told the Bundestag that “the darkest and most horrific chapters of German history were written at Auschwitz and Birkenau.”

Kohl returned in the summer of 1995 after having visited Israel. He and Polish Foreign Minister Wladyslaw Bartoszewski, who had been imprisoned at Auschwitz-Birkenau from September 1940 to April 1941, laid a wreath at the international monument.

“The suffering and death, the pain and the tears of this place, leave us speechless,” Kohl wrote in the guestbook. “Commemorating together, mourning together and acknowledging our will to be together — that is our hope, our path.”

These heart-felt words may well have inspired Merkel, Kohl’s protege and successor. One can only hope that her successor will be as committed to these goals as she has been during her chancellorship.