Anne Frank, the inspirational Dutch Jewish diarist, would have been 90 this year had she lived through the Holocaust.

Anne, of course, was not the only Jewish adolescent whose precious life was snuffed out by the Nazis and their collaborators. Lest we forget, one million Jewish children were murdered during the Shoah, a tragedy that staggers the imagination.

In the Italian documentary #Anne Frank: Parallel Stories, which opens in Toronto on October 21, Sabina Fideli and Anna Migotto take a fresh look at Anne Frank and also delve into the lives of five other Jewish women who were singled out for persecution during that terrible era. Three are from Italy, one from the Czech Republic and another from France.

The focus, from start to finish, is on Anne Frank, whose diary has been translated into numerous languages. Excerpts are read periodically by the actress Helen Mirren, who seems genuinely moved by her poignant entries.

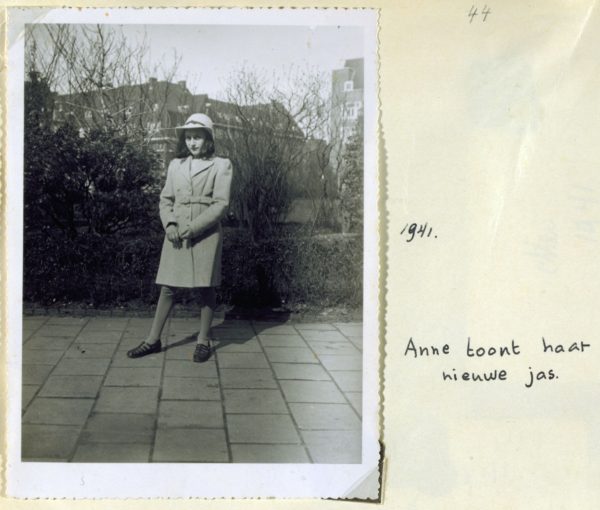

A bright and lively person, she was the daughter of German Jews who settled in Holland after the accession to power of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime. She received a diary as a birthday gift from her parents in June 1942 when she was 13 years old. A month later, she and her family — father Otto, mother Edith and sister Margot — went into hiding in Amsterdam, where Jews were being rounded up and deported to the Westerbork transit camp en route to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

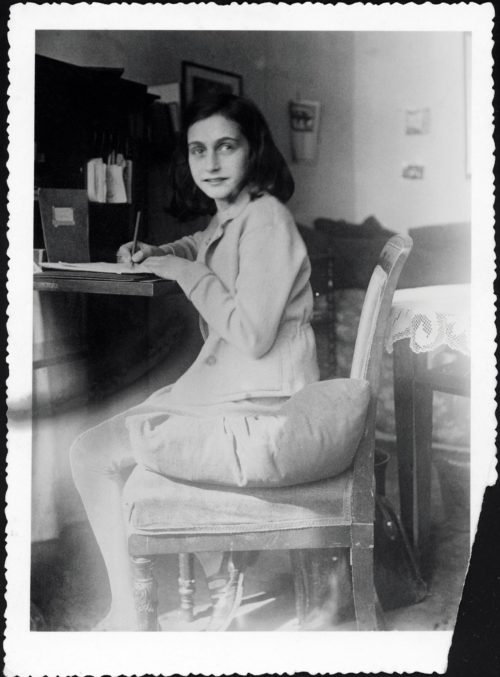

For the next two years, they were confined to an almost windowless attic they shared with a few Dutch Jews. During this period, when three-quarter of Holland’s Jewish citizens were systematically killed, Anne put pen to paper.

As she eloquently filled the pages of her diary, the five other girls learned what it was like to be an outcast in their respective countries.

Arianna Szorenyi, an Italian of half-Jewish descent, was 11 years old when she was sent to a succession of concentration camps. The kindergarten-age Italian sisters Andra and Tatiana Bucci were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Helga Weiss, a Czech Jew born in the same year as Anne, was transported to the Terezin camp, near Prague, and endured her ordeal by drawing pictures. Sarah Lichtszteyn-Montard, a Polish Jew raised in Paris, was arrested in the summer of 1942, but she and her mother managed to escape and hide themselves. Looking back, she says, “My children are my revenge against the Nazis.”

Their tales of survival, while admirable, are not sufficiently fleshed out to be compelling.

Anne Frank’s story, though retold many times, still strikes a chord.

In one of her earliest entries, she says she wants to go on living, even after her death. Considering her iconic status as the best known victim of the Holocaust, this is a remarkably prescient comment. As World War II drags on, steamrolling over European civilians, Anne Frank makes another piercing observation. We must assume that most Jewish deportees are being murdered, she writes in a feat of deductive reasoning.

She succumbs to sadness and despair when she realizes she is “surrounded by darkness and danger.” Her mood brightens when she looks through the skylight and sees the branches of a tree, the sky and the sun.

Betrayed by a German collaborator, Anne and her family were deported to Westerbork in September 1944, less than a year before Holland was liberated by Canadian troops. She and her sister died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen in the spring 1945, their bodies dumped in a common grave containing the corpses of thousands of concentration camp inmates.

Seventy four years after her tragic death, one can only imagine how accomplished a person she could have been had she survived. #Anne Frank: Parallel Stories leaves a viewer with this indelible impression.