Polish Jews invested high hopes in Poland’s campaign for independence from Russia and its rebirth as a sovereign state in 1918. But the period during which these events transpired coincided with the most widespread and possibly deadliest antisemitic violence in modern Polish history.

Nearly 300 pogroms and anti-Jewish riots erupted in areas either still under the control of the Russian Empire or in independent Poland itself. Approximately half of these violent incidents occurred in the province of Galicia, 11 percent of whose inhabitants were Jewish.

William W. Hagen, a professor emeritus of history at the University of California, has written the first scholarly account of these outbreaks, which unfolded between the start of World War I and the eruption of the Polish-Soviet War.

Hagen’s deeply-researched book, Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland, 1914-1920 (Cambridge University Press), is both exhaustive and chilling in scope and tone.

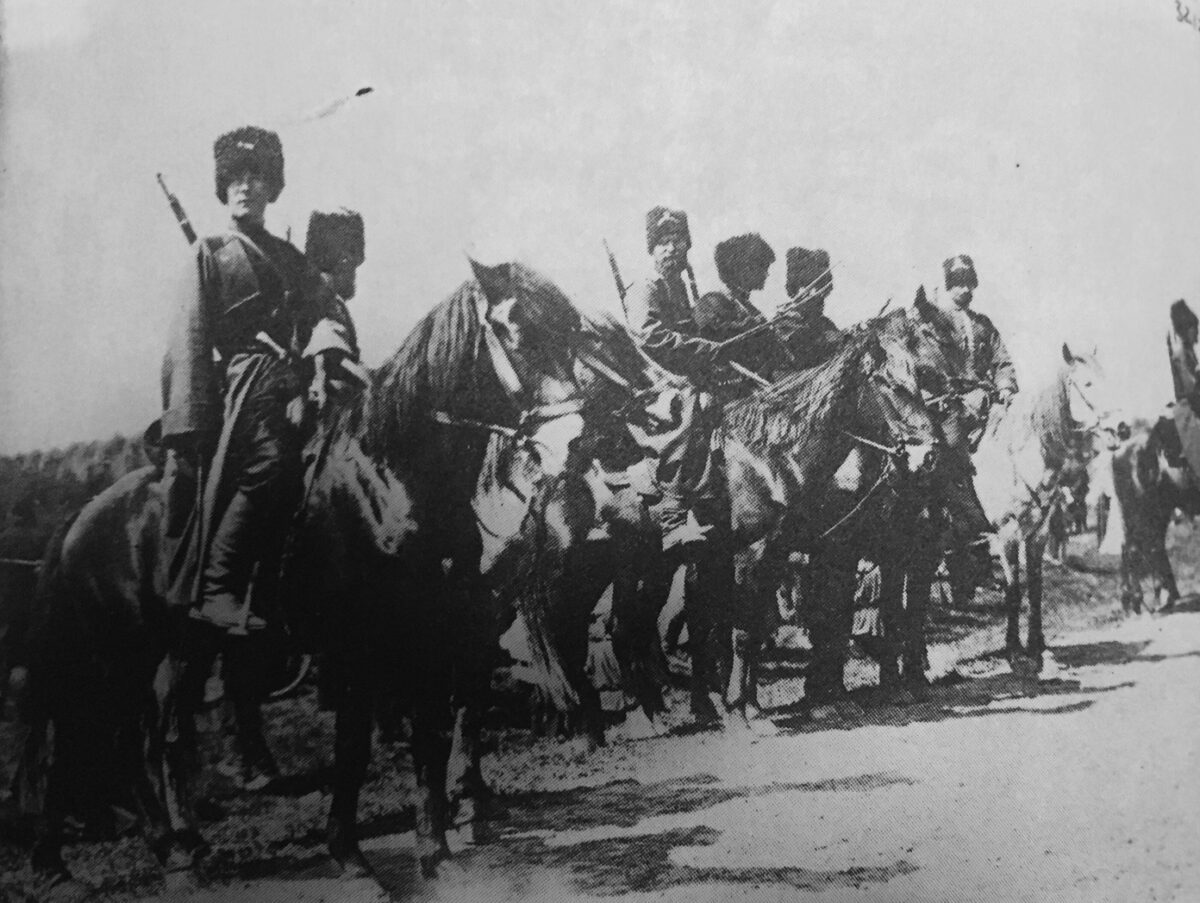

Jews were victimized by ethnic Polish and Ukrainian civilians and by Polish soldiers and Russian Cossacks allied with Poland against the Soviet Red Army. Yet, as Hagen points out, these atrocities were condemned by the Polish government from 1918 onwards.

The anti-Jewish animus that exploded into murderous violence in the first year of the war was deeply rooted in local culture, he says, citing two sources.

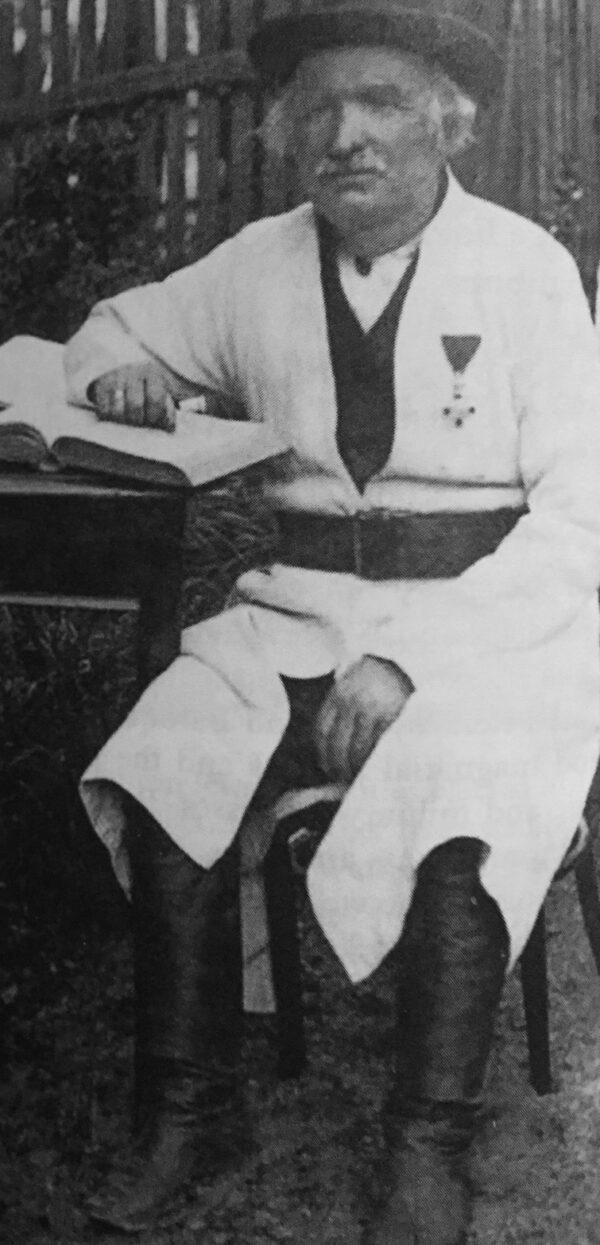

Jan Slomka, a Galician farmer and village mayor, published his memoirs in 1912 in which he attacked Jews as cynical exploiters of Christian peasants. He accused Jewish merchants of stoking alcoholism, blamed Jewish moneylenders for bankrupting farmers, and regarded Jews as Bolshevik sympathizers.

Franciszek Bujak, a Jagiellonian University historian and a member of the Polish delegation at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, wrote a pamphlet in which he defamed Jews. He claimed they were anti-Polish, unscrupulous in their business dealings, and partial to radicalism and revolution. Bujak’s solution to the problem was a cut-and-dried. He believed that Jews should assimilate fully into Polish society, relinquishing their Jewish heritage, and that culturally distinctive Jews should leave Poland altogether.

Hagen suggests that the views held by Slomka and Bujak were embedded in mainstream Polish beliefs, customs and folk art and endorsed by the Roman Catholic church. “In historically Polish-ruled lands, popular anti-Judaism was formidably present, alongside more benign, centuries-old modes of Christian-Jewish coexistence,” he writes.

Much of Hagen’s work is a methodical examination of the pogroms and riots that broke out in a succession of small towns and in cities such as Krakow, Lwow and Rzeszow.

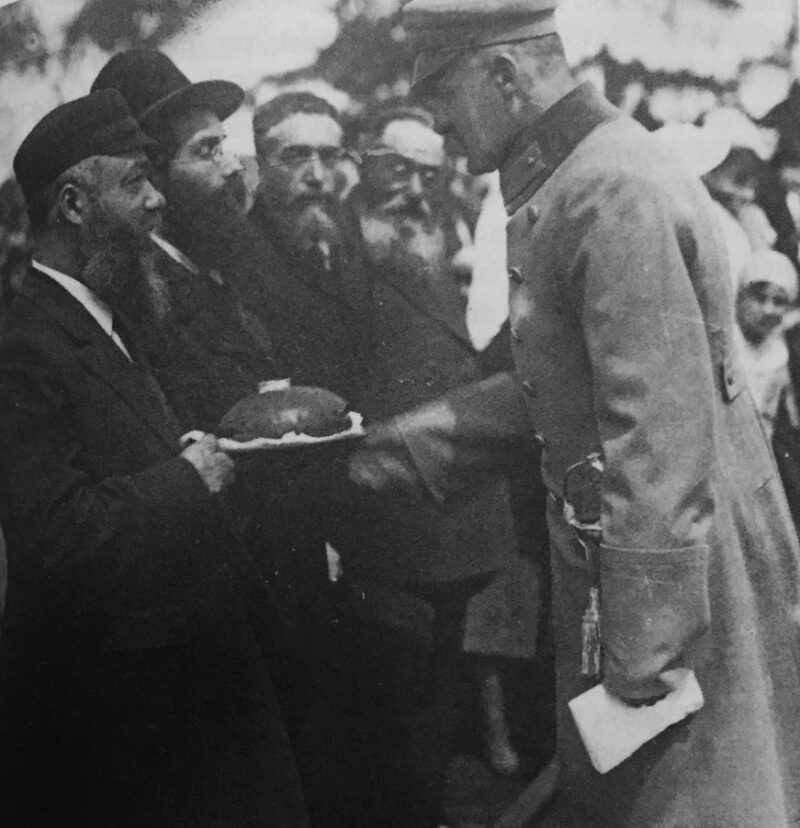

Polish leaders ranging from Jozef Pilsudski to Ignacy Paderewski denounced pogroms, even while sometimes excusing or justifying the violence on the grounds that Jews were animated by anti-Polish feelings.

Still other Poles, like Interior Minister Stanislaw Wojciechowski, declared that Jews possessed the same civil rights as the “native Polish population,” thereby perpetuating the antisemitic myth that Jews were foreigners in their own country.

Władysław Sikorski, an army commander and an important figure in the Polish government-in-exile during World War II, signed a military communique during Poland’s war with the Soviet Union that reeked of antisemitism.

It read, “Bolshevik Muscovite bands under Jewish commissars’ command dared to cross the glorious Polish Republic’s border … Sharpen your scythes, your pitchforks, your axes and pursue the enemy. Let the accursed Bolshevik bands and their Jewish commissars feel the strength of your arm on their necks …”

According to Hagen, the focus of pogroms in 1918 and 1919 shifted. Jews, having been previously criticized for exploiting Christians for economic gain, were now faced with the twin accusations that they were not Polish patriots and supported the Bolshevik cause.

In closing, Hagen says, “Recovery of (Polish) statehood went together with determination among many Christians to break Jewish power not only through the democratic ballot box but also through pogrom looting and destruction, and even violence …”

He adds, “The subterranean power of Judeophobic anxiety in Polish popular culture manifests itself in the tendency among those gripped by it to summon “zydowszczyzna” as explanation for newly arisen threats to Christian society or newly perceived weaknesses within it. This tendency survives today, although the Jewish presence has shrunk enormously in Poland.”