Jonathan Hayoun’s four-part documentary about the world’s longest hatred, Anti-Semitism: 2000 Years Of History, is an edifying survey of a mutating pathological phenomenon that shows no signs of abating.

Now available on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform, this nearly four-hour French production, with English subtitles, is panoramic in scope and substance.

The narrative is supplemented by 3D historical reconstructions, illustrations, photographs, newsreels and commentaries from European and American historians and public figures. As a primer, it is educational, illuminating and, ultimately, unsettling and disturbing.

It may come as a surprise that the first known incident of anti-Jewish violence occurred in antiquity. In 38 AD, in the cosmopolitan Egyptian city of Alexandria, a Greek mob attacked Jews. Witnessed by the philosopher Philo, it was an isolated case of anti-Jewish animus during ancient times.

A mistrust of Jews by Romans gave way to negative portrayals of Jews after the death of Jesus, a Jew by birth and upbringing. Although the Romans crucified Jesus, Jews were accused of deicide.

With Christianity imposed on the Roman Empire by the emperor Constantine, Jews were stigmatized, excluded from some professions, and forbidden to build synagogues.

For the next few centuries, Jews were tolerated in Christendom under conditions of servitude and humiliation.

Shifting to Islam, the documentary glosses over its founder, Mohammed the Prophet, and explains the inferior status of Jews as dhimmis under the Pact of Umar.

Jews prospered and lived peacefully in Muslim-controlled Spain. In 1027, the sultan of Grenada appointed a Jew, Samuel Ibn Nagrela, as prime minister. His son, Joseph, inherited his father’s position, but was assassinated by resentful Muslims.

In neighboring France, where Rashi — a Talmudic sage — thrived in Troyes, Christian clerics attempted to create boundaries between Jews and Christians.

Pope Urban II, in 1095, called for the Christian conquest of Jerusalem. With the launching of the Crusades, the charge of deicide was resurrected against Jews. En route to the Holy Land, crusaders murdered Jews in massacres, in what would be the first recorded massive wave of anti-Jewish violence.

The church hierarchy took a dim view of it, but after the Crusades, anti-Judaism penetrated European societies. With Christians now accusing Jews of ritual murder, Jews were increasingly dehumanized.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, anti-Jewish sentiment hardened into dogma. Jews were relegated into positions of inferiority and regarded as instruments of evil.

Singled out as aliens, Jews were forced to wear distinctive clothing and were depicted with hooked noses. Pope Innocent III and King Louis IX of France, among others, encouraged this racist trend.

As the decades wore on, Jews were gradually forced into closed residential spaces, or ghettos, negatively identified with wealth and royal power, and expelled from Britain and France.

Alongside efforts by Christian monarchs to reconquer Muslim-held territories in Spain, Spanish authorities exerted mounting pressure on Jews to convert to Christianity. A small proportion of Jews complied, and some of these converts achieved prominence. But eventually, the Catholic Church concluded that the New Christians were insincere. They were rooted out during the Inquisition. And in 1492, Jews who refused to embrace Christianity were expelled from Spain. Jews in Portugal met the same fate.

The expulsion scattered Jews to North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, Amsterdam, and eastern Europe. By the late 17th century, 90 percent of the world’s Jews lived in what is now Poland, where Yiddish was their vernacular.

With the Enlightenment, a turning point in Jewish history, conditions improved for Jews. France, in 1791, emancipated Jews and gave them citizenship. It was the first country in Europe to do so.

New forms of anti-Jewish animosity emerged in the 19th century.

Writing the first book about human races in 1853, Arthur de Gobineau classified Jews as a separate Semitic race inferior to white Christians. Francis Galton, a British scholar, endorsed Gobineau’s half-baked theory. In one bold stroke, racial antisemitism replaced religious anti-Judaism as a guiding force.

The word “antisemitism” itself was coined by Wilhelm Marr, a German antisemite, in 1879.

The documentary lists two other Europeans who were instrumental in defaming Jews — Edouard Drumont, the French journalist/propagandist who was active during the Dreyfus affair, and Karl Lueger, the mayor of Vienna whom Adolf Hitler admired.

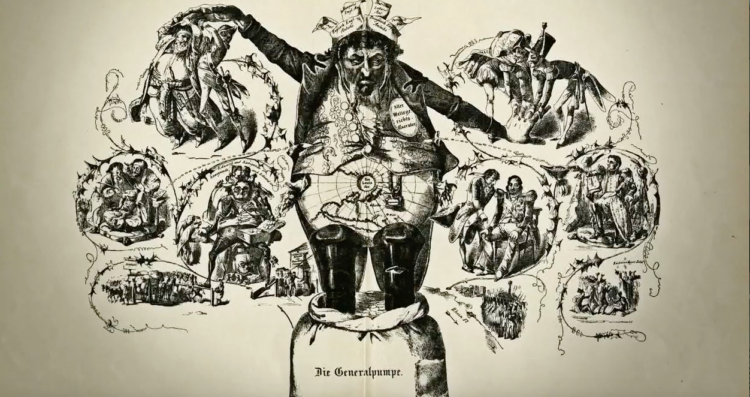

During this period, antisemitism swept through the Russian Empire, the antisemitic tract The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published, and Theodor Herzl, a Viennese journalist, founded the modern Zionist movement, triggering the immigration of Jews to Palestine.

The massacre of Jews in Kishinev, in 1903, was the first pogrom of the 20th century. But further atrocities lay ahead.

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution emancipated Russian Jews, but convinced counter-revolutionary forces that Jews were inherently communists. This perception, which took root in Germany after its defeat in World War I, was promoted by the deeply antisemitic Nazi movement.

The documentary skims over the surface of the Holocaust, a catastrophe which wiped out one-third of Europe’s Jews.

More than 200,000 Polish Jews returned to Poland after the war, but many packed their bags again after the 1946 Kielce pogrom, which was grounded in the medieval myth of blood libel.

The birth of Israel stirred antisemitism in the Arab world, driving nearly 850,000 Jews out of countries ranging from Egypt and Syria to Iraq and Yemen. In the years ahead, antisemitic caricatures of Jews appeared regularly in the Arab press, and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was published in Arabic.

Antisemitism in the United States is given short shrift and is barely broached with respect to Canada.

In the final episode, Pope John XXIII’s historic Second Vatican Council is rightly described as the church’s break with anti-Judaism.

The anti-Zionist campaigns in the Soviet Union after World War II, particularly the infamous Doctors’ plot, are mentioned as well, as is the United Nations’ Zionism-is-racism resolution, which was passed in 1975 and revoked in 1991. From this perspective, anti-Zionism has become the “new face” of antisemitism.

The documentary classifies Holocaust deniers as “falsifiers of history,” as Robert Badinter, the former justice minister of France, succinctly says.

In closing, it cites two antisemitic attacks of fairly recent vintage in France and Germany, which were respectively perpetrated by an Islamic radical in Toulouse and a German neo-Nazi in Halle.

These incidents underscore the lamentable fact that Jews are victimized by both Muslim and Christian antisemites, and that the wellsprings of antisemitism run deep.