The 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia was a moment of emancipation and liberation for oppressed Russian Jews, a deliverance from the injustices of the previous czarist regime.

But within months of seizing power, the Bolshevik leadership was faced by the specter of pogroms in the former Pale of Settlement, a region of western Russia where the vast majority of Jews, comprising four percent of Russia’s population, had been forced to live.

Virtually all the outbreaks of violence against Jews were carried out by pro-czarist right-wing forces hostile to the revolution. But to the shock and dismay of the new revolutionary government, some of the pogromists were Bolsheviks and Red Army soldiers.

As Brendan McGeever writes in Antisemitism and the Russian Revolution (Cambridge University Press), the pogroms erupted in the early weeks of 1918, reached a peak in 1919 and continued unabated into the first years of the 1920s. At least 2,000 pogroms took place, claiming the lives of 50,000 to 60,000 Jews in what he describes as “the most violent assault on Jewish life in pre-Holocaust modern history.”

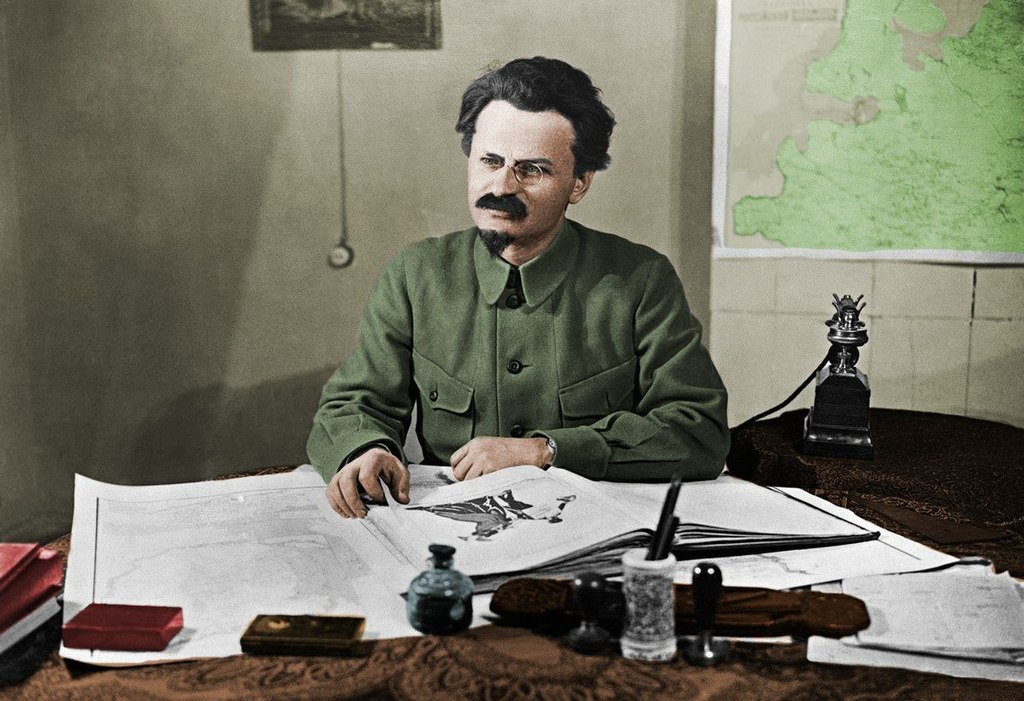

The bulk of the antisemitic atrocities were carried out by the white armies of Anton Denikin and the Ukrainian militias of Simon Petliura, he notes. The Red Army, headed by the Jewish communist Leon Trotsky from 1918 to 1925, was responsible for almost nine percent of the unprovoked attacks.

For decades, there were no serious attempts by scholars to examine unofficial Bolshevik participation in the pogroms. McGeever’s ground-breaking and illuminating book is the first work to do so.

A University of London sociologist, he reminds readers that antisemitism was present in both the counter-revolutionary and revolutionary movements in Russia. But as he adds, the Bolshevik leadership staunchly opposed antisemitism and viewed the pogroms as “a threat to the survival of both Jews and the revolution.”

He goes on to say that there was a tangible Soviet response to pogroms in the form of a state institution known as the Committee for the Struggle Against Antisemitism. McGeever says the committee was not Bolshevik in origin, having been established by a group of non-Bolshevik Jewish radicals in the Evsektsiia, the Jewish section of the Russian Communist Party.

Formed in August 1919, its purpose was to instil in the working class, the Red Army and the peasantry a cultural and political opposition to antisemitism. But within a matter of weeks of its formation, it was closed.

The pogroms that broke out during the 1918 civil war were the third wave of anti-Jewish violence in modern Russian history. The first ones occurred following the assassination of the czar Alexander II and unfolded between 1881 and 1883. The second ones took place in the city of Kishinev in 1903 and during the failed 1905 revolution.

Until 1881, Russian socialists rarely addressed Jewish-related matters. In the wake of the pogroms, the so-called Jewish question assumed greater importance. Nonetheless, some left-leaning populists welcomed the pogroms, hoping they would awaken the masses and help sweep away all “exploiters,” including Jews. Still other populists, such as Petr Lavrov, condemned antisemitism as the “most tragic epidemic of our era.”

From the 1890s onward, Russian socialists adopted a critical position with respect to antisemitism, contending that pogroms played into the hands of reactionaries. But from 1903 to 1905, May Day demonstrations in the cities and towns of the Donets Basin were repeatedly cancelled out of fear that antisemitic outbursts would mar the festivities.

Bundist figures like Vladimir Medem accused Russian socialists and social democrats of neglecting to confront antisemitism. In his memoirs, Medem recalls that Leon Trotsky, a Jew, minimized antisemitism, dismissing it as “nothing more than a consequence of the universal lack of consciousness among the broad masses.” According to Medem, Trotsky argued that the focus on Jews was “superfluous” and naively predicted that antisemitism would “fade away” after the masses had been brought to “a state of general awareness.”

As McGeever points out, the year 1917 transformed Jewish life in Russia in practically one fell stroke. With the abdication of czar Nicholas II and the creation of the provisional government, more than 140 antisemitic statutes were removed overnight. As the restrictions were lifted, there was an explosion of anti-Jewish attacks. To revolutionaries, reformist socialists and liberals, they were regarded as a form of “restorationist counter-revolution.”

Bolshevik leaders themselves sometimes encountered such crude antisemitism. Vladimir Lenin’s future secretary, Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, personally encountered mobs openly calling for pogroms.

“For the Bolshevik leadership, revolutionary politics was simply incompatible with antisemitism,” writes McGeever. “The two were antithetical. As a front-page headline in the party’s main newspaper Pravda would put it, ‘To be against Jews is to be for the czar.'”

Yet this slogan was upended by Red Army soldiers in 1918 and 1919 when they shouted, “Smash the Yids, long live Soviet power.” To such Russians, McGeever notes, “the Jew” became a “principal signifier of anti-bourgeois sentiment.”

Red Army troops were involved in pogroms in, among other cities, Bryansk, Hlukhiv and Uman. In Hlukhiv, a city in the Ukraine, the main Bolshevik slogan was “eliminate the bourgeoise and the Yids.”

Despite the fact that Bolshevik leaders opposed antisemitism, they did not broach the topic even once in their first nine months of power.

The first known discussions on antisemitism within the central institutions of the Soviet government took place in April of 1918. Joseph Stalin, an up-and-coming official, participated in these sessions. One of its Jewish participants, Grigory Zinoviev, a high-ranking Bolshevik official, condemned antisemitism as a type of “national hatred implanted into the consciousness of workers by the bourgeoise.”

Three months later, the Bolshevik regime issued its first official decree decrying anti-Jewish violence. Lenin endorsed it, instructing all Soviet institutions “to take uncompromising measures to tear the antisemitic movement out by the roots” and place “pogromists and pogrom agitators outside the law.”

In 1919, Soviet President Mikhail Kalinin inserted himself into the debate when he declared, “The Central Committee of our party does pay special attention to the political struggle against antisemitism. Your struggle against antisemitism is part of our eternal work because it is pure counter-revolution.”

But in response to claims by pro-czarist forces that Bolshevism was Jewish and that Jews controlled the Soviet state, Lenin ordered a reduction in the number of Jews in the government and the Red Army.

That sensitive issue consumed Trotsky, as McGeever observes. Both in 1917 and 1922, he refused invitations from Lenin to accept a senior position in the government. In 1923, he appeared before a joint session of the Central Committee and the Central Control Committee to explain his position.

“The thing is, comrades, there is a personal element in my work,” he said. “… This is my Jewish origin … I thought it would be much better if there were no Jews in the first revolutionary Soviet government … I was right … Remember what a hindrance it was in some acute moments … when our enemies in their agitation used the fact that the Red Army was headed by a Jew. It interfered greatly …”

Due to the economic crisis of the late 1920s, anti-Jewish sentiment rose sharply in Soviet society, in part because no government campaign against it had been waged among workers and Bolshevik Party members.

At the 1927 party congress, the matter was firmly addressed. “What followed was an unprecedented campaign exceeding in scale and scope anything seen,” says McGeever. “From mass meetings to official investigations and scores of newspaper articles and published materials, the issue of antisemitism was brought before Soviet audiences like never before.”

As he adds, this campaign left “a lasting imprint on a generation of Soviet Jews and helped foster a sense of belonging and identification with the Bolshevik project, despite the continuation of antisemitism in everyday social life.”

But as Stalinist hostility to “particularism” took hold, the Evsektsiia was closed, signalling an end of the government’s “cultivation of Jewish cultural politics.” Concurrently, the state campaign against antisemitism ground to a halt, he says.

“Worse was to follow. As the nightmare of High Stalinism descended, an entire layer of Soviet Jewish activists, including many of the key figures encountered in this study, were murdered in the Great Terror that scarred Soviet society for the rest of the century and beyond. Soviet antisemitism survived Stalinism. The campaign against it did not.”