Arab intellectuals and leaders have long been animated by the holy grail of Arab nationalism, an ideology which proclaims that Arabs are one nation, glorifies Arab civilization, language and literature and espouses the necessity of a single Arab state. This utopian idea was in its heyday during Gamal Abdel Nasser’s presidency of Egypt, but in recent decades, it has lost much of its glitter and appeal.

Adeed Dawisha, an American scholar at Miami University in Ohio, deftly explores its origins and permutations in Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: From Triumph to Despair, published by Princeton University Press. In this authoritative book, originally published in 2003 and now updated, he explores its early stirrings, its golden age and its demise.

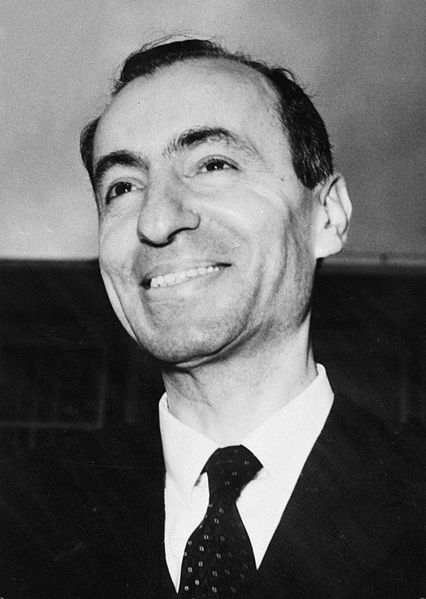

In Dawisha’s judgment, the foremost theoretician of the Arab nationalist movement in the last century was Sati al-Husri, a Syrian Muslim who was born in Yemen in 1882 and spent his formative years in Constantinople. A senior official in the Ottoman bureaucracy who held posts in the Balkans and in Syria and Iraq and who spoke Arabic with a slight Turkish accent, he argued that Arab states were the artificial creations of Western imperialist powers like Britain and France.

Asked why Israel had prevailed over seven Arab states in the 1948 war, he replied that the Arabs would have fared far better had they been united under the banner of one Arab state. Husri’s ideas were adopted by the founder of Syria’s Baath Party, Michel Aflaq, who bemoaned the prevalence of “counterfeit countries and statelets” in the Arab world.

Dawisha agrees that “regional particularism” was an obstacle in the path of Arab nationalism. “Iraqi, Syrian (and) Egyptian identities competed with the larger, all-encompassing Arab identity, he writes.

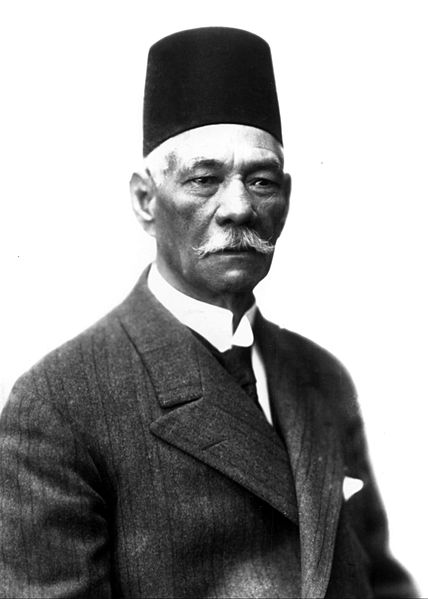

Egypt was a prime example. Sa’ad Zaghloul, the father of Egyptian independence, was doubtful about Arab nationalism. “If you add one zero to another zero,” he said mockingly, “then you add another zero, what will be the sum?”

The proliferation of colloquial Arabic dialects, the existence of tribalism, the Sunni-Shiite divide and the reluctance of Kurds and Druze to assimilate into Arab culture were also major factors in inhibiting its growth. Arab Christians, though, were supportive. “This was to be expected since the Christians had the inferior standing of a religious minority in an Islamic state,” he observes.

Dawisha argues that Jewish immigration to Palestine in the 1920s and 1930s united Arabs of all stripes, from nationalists to Islamists. “From their different loyalties and perspectives, they all would agree on the need to resist the demographic changes that were under way in Palestine. The expansion of educational opportunities, the introduction of the radio and the proliferation of newspapers made the Palestine issue that more accessible.”

He goes on to say that the struggle between Palestinian Arabs and Jews in British Mandate Palestine fostered a belief in the notion that Arabs shared similar interests, concerns and aspirations and were duty bound to resist the Zionist objective of creating a Jewish state in Palestine. Fawzi al-Qawuqchi, a Syrian who served as an officer in the Iraqi army, fell under the influence of this idea. Resigning his commission, he would lead a group of volunteers to fight alongside the Palestinians in the first Arab-Israeli war.

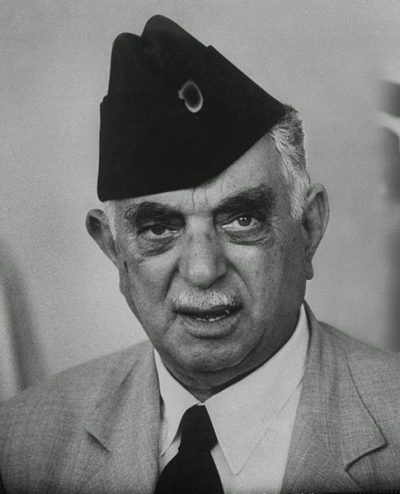

The upsurge of violence in Palestine in the late 1930s also had an impact on the prime minister of Iraq, Nuri al-Said. At a meeting of Arab leaders in Cairo in 1939, he proposed the formation of the Arab League. It came into being in 1944, signalling the first tangible achievement of Arab nationalism.

In 1943, he submitted a two-stage plan for a Fertile Crescent Union. During the first phase, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Trans-Jordan would amalgamate into one state, with some autonomy guaranteed for Jews in Palestine and Christians in Lebanon. Once this entity of Greater Syria was established, the second phase would kick in and Iraq would become a member. The concept died on the drawing board, but the eruption of the first Arab-Israeli war in 1948 galvanized supporters of Arab nationalism.

In a show of Arab unity, five Arab armies attacked the newly-created state of Israel, which had been proclaimed by David Ben-Gurion. Divisions soon appeared. With King Abdullah of Trans-Jordan coveting Palestine, Syria, Iraq and Egypt grew suspicious of his ulterior motives. And on the battlefield, Dawisha notes, there was a noticeable lack of Arab coordination.

The Arab nationalist movement gained impetus after Nasser, a young officer in the 1948 war, assumed power in Egypt. Nasser’s decision to nationalize the Suez Canal Company, plus the invasion of Egypt by France, Britain and Israel in 1956, gave it another shot in the arm.

The amalgamation of Egypt and Syria into the United Arab Republic in 1958 was the high-water mark of Arab nationalism. Nasser, however, sowed the seeds of the UAR’s destruction by his insistence of Egyptian domination in every sphere. “The problem was that for all intents and purposes, there could be no equality between a country of twenty six million (Egypt) and another of four million (Syria). Syria had little choice but to follow in Egypt’s shadow, and to do things the way Egyptians did them. Especially distressing to the Syrians was the spectacle of their administrative, legislative and military systems being gradually absorbed into Egypt’s.”

Dawisha contends that the 1967 Six Day War was Arab nationalism’s “last stand.” As a result of Israel’s smashing victory, Nasser, far from being able to pursue the goals of Arab nationalism, was forced to concentrate on regaining the Sinai Peninsula from Israel. “Egypt’s primary goal now became ‘the eradication of the consequences of the defeat.'” Its involvement in inter-Arab affairs were now totally dependent on “the consummation of this overriding objective.”

Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat, dumped Arab nationalism and adopted an Egypt-first policy.

To the Palestinians, who had relied on Arab assistance to “liberate” Palestine, the bitter outcome of the war was a sign of the impotence of Arab nationalism.

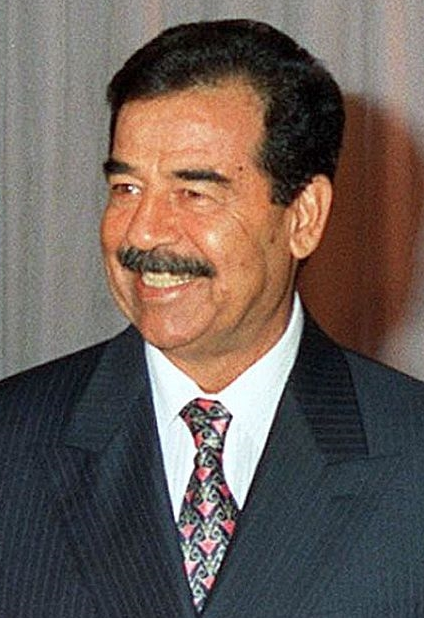

According to Dawisha, it took another hit when Syria, the so-called “beating heart” of Arab nationalism, lined up behind Tehran in the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War. Iraq’s strongman, Saddam Hussein, was himself archly dismissive of Arab nationalism. As he said, “We must see the world as it is. The Arab reality is that the Arabs are now twenty two states, and we have to behave accordingly.”

During the 1980s and 1990s, Arab nationalism was overtaken by radical Islam, which challenged the status quo in the Arab world.

In closing, Dawisha writes, “With all its faults and shortcomings, the many achievements of Arab nationalism were undeniable: It led the struggle for independence from the outsider. Under its umbrella, Arab states took determined steps toward social and economic modernity. It bestowed on the Arabs a sense of dignity after years of colonial humiliation. And it endowed the nationalist generation of the era with an abiding belief in an inevitable future of progress and success. This was the legacy of Arab nationalism.”