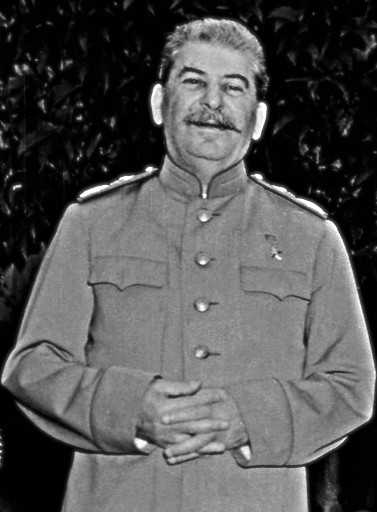

The British-made satirical film, The Death of Stalin, released last year, made fun of the absurdity of Soviet “justice” in the years when the dictator ruled his empire like an Oriental satrap.

Accusations against people could come out of thin air. Trials, preceded by torture to extract confessions, took minutes. A bullet in the head by the secret police soon followed.

In real life, of course, this was no joke.

The final years of Stalinist repression in the eastern bloc countries where Communism had been imposed by Russian bayonets saw the wholesale execution of Communist apparatchiks, mainly Jews, who despite their loyalty to Moscow during the war years, suddenly found themselves accused of “bourgeois nationalism,” “Titoism,” “Trotskyism,” “Zionism,” and numerous other ideological crimes.

In reality, Stalin was cleaning house, getting rid of genuine revolutionaries, who had the intelligence and stature to challenge diktats coming from the Kremlin, and replacing them with sycophantic apparatchiks who owed their careers wholly to their Soviet master.

Such show trials took place throughout the east European satellite states, but the ones in Czechoslovakia in November 1952 were particularly gruesome.

The Communist Party had taken over the Czech government in 1948, but Stalin was greatly disturbed when Yugoslavia, under Josip Broz Tito, broke from his control that same year.

He ordered a purge in Czechoslovakia that would be intimidating. Fourteen Czech officials were chosen, chief among them Rudolf Slansky, the secretary general of the Communist Party. Eleven of the accused were Jews.

This was no coincidence, as Stalin in his final years had become increasingly paranoid and antisemitic. He was apparently also angry that Israel, born four years earlier with considerable Soviet and Czech help, had not become a Communist state.

The anti-Jewish character of the Slansky trial was part and parcel of the late Stalinist turn toward antisemitism and was introduced into the case by Soviet advisers, who encouraged Czech investigators to stress the dangers of a purported world Zionist conspiracy.

Antisemitism was also visible within the Czechoslovak Communist Party. Officially deplored by the Communist regime, anti-Jewish sentiment took form as a struggle against Zionism and cosmopolitanism.

Among the leadership, the party ideologue Vaclav Kopecky engaged in antisemitic diatribes. He repeatedly spoke out against Zionism and cosmopolitanism, depicting Jews as foreign, bourgeois, and unassimilated.

The indictments were prepared, the accused were arrested and isolated, and after some months of “interrogation,” they all pleaded guilty. They were forced to confess to being part of a Zionist conspiracy, with Zionism understood as a proxy for Western imperialism.

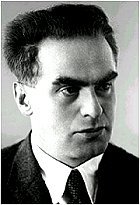

Eleven of the defendants, including Slansky, were hanged. Three were given life sentences. Those three, including Artur London, were released after Stalin died. They were posthumously rehabilitated in 1968 during the “Prague Spring” period of liberalization.

Stalin launched his own anti-Jewish campaign within the Soviet Union with the January 1953 announcement of the so called “Doctor’s Plot,” in which a number of Jewish doctors were accused of using their medical access to harm and kill some of the Soviet Union’s leading personalities

The openly antisemitic character of these events came as a profound shock to many Jews and forced them to reexamine their positions vis-à-vis Zionism, Communism, and the Left.

The Slansky trial has been documented in films. In 1970, the Greek-French film director and producer Costa-Gavras made The Confession. The screenplay was based on the book of the same name by one of the defendants in that trial, Artur London. In 2001, a Czech-born American director, Zuzana Justman, made a documentary on the same subject, called A Trial in Prague.

Now, 66 years later, actual archival footage of these events has come to light. Six hours of 35-millimeter black-and-white film and 80 hours of voice recordings, much of it mould-damaged, believed to cover most of the eight-day proceedings, have been found.

They were stashed in 14 metal and six wooden boxes in the basement of a bankrupt former metal research business in Panenské Brezany, near Prague.

The boxes contained image and sound negatives, duplicate copies, tape recorder tapes, combined copies and copies of original documents from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

Plans to turn the trial footage into a propaganda film were shelved after Stalin died in March 1953 and so were never made public. They are a rare depiction of Stalin-era show trials, very few of which have available long-form footage.

Historian Petr Blazek and filmmaker Martin Vadas inspected the material in mid-March and revealed that it included a filmed record of the 1952 Slansky show trial. It is likely that the boxes were transported to the plant shortly after the Velvet Revolution overthrow of the Communist regime in 1989. They remained hidden there for 29 years.

The material is now with the Czech National Film Archive, which hopes to restore the material to make it available for public viewing. “The priority is to make the footage safe,” said Michal Bragant, the archive’s chief executive. “But it will be even safer once it’s publicly available, because we also need to make the knowledge safe. We still have not learned enough from the 20th century. The more people learn about it and the horror of the show trials, the safer we will be.”

No truer words were ever uttered.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.